At Fublis, Design Dialogues is our dedicated platform for exploring the minds shaping contemporary architecture and design. In this edition, we are honored to feature AMORV—a multidisciplinary design practice that approaches architecture not as static construction, but as a living, evolving relationship between people, place, and matter.

Led by Jamie van Lede and Mira Matic, AMORV’s work moves across scales and typologies, from zero-energy homes to experimental interiors and material libraries. Their philosophy revolves around a simple yet profound idea: architecture with soul. Rooted in inquiry, listening, and deep ecological awareness, their projects reflect a commitment to emotional resonance, behavioral adaptability, and material integrity.

In this in-depth conversation, Jamie reflects on the importance of designing for life—how relationships, not forms, give spaces their vitality; how abstract metaphors like “the swarm” can shape fluid workplaces; and how honoring the wisdom of land and culture can transform buildings into truly living structures. Whether working on an adaptive office for Foodvalley or the bioclimatic Villa Fano in Madagascar, AMORV’s approach resists formula and embraces emergence.

This interview is a window into their evolving ecosystem of people, ideas, and places—and a powerful reminder that architecture is not just a technical act, but a cultural, ecological, and poetic one.

AMORV’s manifesto speaks about “spaces full of soul.” In your view, what gives a space its soul—and how do you design for something so intangible, yet deeply felt?

AMORV: The question that drives us! Rationally, it’s a difficult one to answer-but intuitively, we all know what it means. We’ve all felt it in the built environment. Some places are alive. Others are not. It’s as simple – and as mysterious – as that.

Under the name Hotel Ausfahrt, we’ve started a series of essays exploring this very mystery: what is life in architecture? Can buildings have a soul? Can budings resonate with the order of nature? We trace this question all the way back to the pre-Socratic philosophers, and move forward through metaphysics, biology, anthropology, psychology, and modern science. Because soul is not a stylistic feature. It’s not a nostalgic longing. It’s a fundamental aspect of life- one that modernism has largely erased, with devastating consequences for our built environment.

If there’s one thing we’ve learned, it’s this: soul does not emerge from form alone. It emerges from relationship. Between space and place. Between people and their patterns of life. Between a building and its environment.

The thinkers who have helped us most in navigating this terrain are Goethe, Alfred North Whitehead, David Bohm, and Christopher Alexander. It is Alexander, in fact, who makes the radical claim that life is an attribute of space – and that this life follows certain patterns, which we as designers can cultivate.

As he writes in The Timeless Way of Building:

“There is one timeless way of building. It is thousands of years old, and the same today as it has always been. The great traditional buildings of the past, the villages and tents and temples in which man feels at home, have always been made by people who were very close to the center of this way. It is not possible to make great buildings, or great towns, beautiful places, places where you feel yourself, places where you feel alive, except by following this way. And, as you will see, this way will lead anyone who looks for it to buildings which are themselves as ancient in their form, as the trees and hills, and as our faces are.”

We believe that architecture – real architecture – is not so much a profession as it is a practice of attention. Of listening before drawing. Of learning how to let places speak again.

The metaphor of ‘the swarm’ became a central spatial concept in the Food Valley project. How did this idea evolve into architectural form—and how did you translate such an abstract, dynamic metaphor into functional, flexible space?

AMORV: It began – as always – by listening.

Foodvalley is not a conventional organization. It’s a movement – an evolving constellation of startups, researchers, corporates, and visionaries working toward a shared mission: to transform the global food system. And that kind of mission needs more than walls and desks. It needs a space that can move as fluidly as the people within it.

The metaphor of the swarm emerged early in our conversations. A swarm is not chaos. It’s a form of intelligence – decentralized, adaptive, always in motion. Each element moves independently, yet collectively they form a coherent whole. That became our guiding principle.

We translated this metaphor into a spatial language of flow and openness. Zones were shaped organically – emerging from routing studies rather than imposed grids. Boundaries remained soft. There are no dead ends – just pathways, pivots, and possibilities. Teams can form, shift, dissolve, and reform. The space accommodates without resisting.

To achieve this, we avoided static structures. Instead, we used freestanding volumes, flexible furniture, and fluid sightlines. Meeting rooms are not boxes but thresholds – with multiple entries and ambiguous edges. Walls suggest direction rather than impose limits. Every part of the interior invites movement, improvisation, encounter.

In a world where most office design still clings to rigidity – fixed desks, rigid hierarchies, closed doors – we aimed for something alive. A place that breathes with its users. A space that supports not only productivity but emergence.

The result is a spatial ecosystem. And like all living systems, it is never finished – always becoming.

©Food Valley by AMORV

©Food Valley by AMORV

Nearly every surface tells a story—from walls made of coffee grounds to goat hair flooring. How do you ensure material storytelling doesn’t become a gimmick but instead deepens the emotional and ecological experience of the space?

AMORV: By grounding it in meaning! Material storytelling only works when it’s more than decorative – when it arises from values, from process, and from care. For Foodvalley, material choices weren’t about aesthetic novelty. They were about alignment. With mission. With matter. With the world we’re trying to help regenerate.

We began by asking – what materials embody the agricultural transition? What carries both ecological intelligence and poetic presence? From that inquiry emerged a constellation of bio-based and circular solutions: goat hair rugs, panels made from mown alpine meadows, walls pressed from spent coffee grounds. Each material tells a story – but not to impress. To connect.

To ensure depth and integrity, we partnered with Material Match Maker – an independent consultant that applies a rigorous methodology to assess sustainability claims. They go far beyond carbon footprints. Their approach includes full lifecycle analyses, supply chain transparency, social conditions of production, and value creation across the chain. In short – they help us ask not only what a material is, but who and what it touches along the way.

With their guidance, we curated rather than displayed. Some materials were integrated into the architecture itself. Others – too experimental to use at scale – were given a place of honour in a material library at the entrance. Not a showroom. A dialogue. A living archive of innovation.

It’s not about spectacle. It’s about resonance. The goal is not to say “look how green we are” – but to evoke a tactile awareness of what buildings are made of, and where they come from. In a time when most people have lost touch with material origins, this felt essential.

Matter, after all, still matters.

©Food Valley by AMORV

©Food Valley by AMORV

You’ve described this interior as ‘a space that moves with you’. How do you technically and spatially plan for behavioral adaptability in a workplace—especially for teams that are constantly evolving like Foodvalley?

AMORV: Adaptability isn’t a feature. It’s a principle – embedded from the ground up.

We designed for transformation rather than permanence. Freestanding elements, modular furniture, writable partitions, and flexible layouts allow teams to reshape their environment as their work evolves. Meeting rooms aren’t boxes but thresholds. There are no rigid zones – only paths, flows, and possibilities.

We also worked with responsive lighting systems – allowing teams to adjust light intensity and atmosphere per activity, season, or time of day. Just like space, light needs to adapt.

Underlying this approach is Stewart Brand’s shearing layers theory from How Buildings Learn – the idea that different layers of a building change at different speeds. By distinguishing structure from furniture, services from surfaces, we designed a space that can evolve organically without losing coherence.

True flexibility, however, goes beyond layout. It’s about behavioural rhythms. Can a space host a sprint in the morning, a lunch in the afternoon, and quiet reflection by evening? At Foodvalley, the answer is yes.

Because a truly adaptable space doesn’t just move with you – it helps you move forward.

©Food Valley by AMORV

©Food Valley by AMORV

You describe AMORV as an ecosystem of people, ideas, and projects. How do you maintain creative coherence across such a dynamic and interdisciplinary structure—especially when navigating different project scales, from exhibitions to zero-energy homes?

AMORV: We don’t.

We believe in emergence – not predefinition. We rarely know in advance what will come out of a collaboration, a cross-pollination, or even a single conversation. We follow the current – not the map.

What starts as an interior project might evolve into a lecture. A workplace design might unfold into an exhibition. A board meeting at our renovated farmstead might be followed by a concert – or spark a collaboration. As long as it brings more life, more presence, more soul, it belongs.

We don’t seek coherence through uniformity, but through vitality. Projects, people, and ideas move through AMORV like currents in an ecosystem – complex, nonlinear, adaptive, and always alive.

You’ve described Villa Fano as a “living structure” that breathes with its surroundings. What were some of the most surprising things you learned from the land, the people, or the climate during the design process—and how did they reshape your architectural decisions?

AMORV: What struck us most – and frankly, saddened us – was how deeply the “white man’s dream” had taken root. We saw modern, imported houses being built across Madagascar – technical, concrete structures that ignored both climate and culture. The dream of progress had replaced the wisdom of place. Traditional knowledge was being erased, often in favor of European aesthetics and foreign materials that had to be shipped in at great cost.

We wanted to offer a counter-narrative. Through thoughtful bioclimatic design – natural ventilation, passive cooling, strategic orientation – we were able to free up the budget for craftsmanship and expression. Beauty didn’t have to compete with performance. In fact, the more we respected the logic of the land, the more generous the project became.

One of the most revealing insights came through a colonial story. Before the arrival of the French, people lived in palm-thatched huts with a small fire always burning inside – not just for cooking, but to ward off termites. When indoor fires were banned under colonial law, people lost that protection and had to rebuild their roofs every few years. We’re not advocating for open fires indoors – but the principle of slow, constant fumigation was elegant, effective, and is now forgotten. What else have we silenced in the name of progress?

Another pivotal moment came when we encountered a large, sacred tree at the heart of the site. We were told it could not be touched – not just for ecological reasons, but spiritual ones. So we didn’t just work around it. We designed with it. The presence of that tree became the emotional and spatial anchor of the project. And that shift – from imposing to responding – opened something up.

In that same spirit, we embraced the tradition of blessing the construction through a local shaman. It wasn’t a token gesture. It was a recognition that building is always a social act – and that real integration means more than just respecting the landscape. It means honoring the invisible relationships that shape a place: the customs, the hierarchies, the ancestral ties. In doing so, the house didn’t just land on the site. It entered into relationship with what was already there. And that, in many ways, is what turned it into a living structure.

©Villa Fano by AMORV

©Villa Fano by AMORV

You call this house a ‘story of listening before drawing.’ In your process, when do you know that you’ve listened enough—and that it’s finally time to put pen to paper?

AMORV: The honest answer is – you don’t. Not in the way we’re used to in the West.

Here in Europe, building typically follows a strict sequence: you draw, you budget, you apply for permits – and only then do you begin. Every line is frozen in advance. Change during construction is punished – legally, financially, and bureaucratically. Once the plan is fixed, listening stops.

But in Villa Fano, it was different.

The ratio of labour to material was almost the opposite of what we’re used to. Locally sourced labour is accessible – materials, especially imported ones, are costly. And permitting doesn’t revolve around technical drawings or structural details. It’s largely about the building’s outline – the main gesture. That gives you room to adapt. You’re allowed to respond.

And that, to us, is how it should be.

Design should not be a closed act. It should remain open to the unexpected. Just like when you were a child building a treehouse – you didn’t start with permits and working drawings. You climbed the tree with a hammer in your hand and a mouth full of nails, and you started building in relationship to the limbs, the wind, the view. No blueprints. No formulas. Just a felt response to a living structure.

That’s how we built Villa Fano.

The drawings were never fixed. They were always allowed to change. I still remember standing on the site just after the structure was up, when a previously hidden view suddenly revealed itself. A breathtaking opening in the landscape. In that moment, you do what you must: you change the plan. Because the building isn’t finished when the drawing is done – it’s only just begun.

©Villa Fano by AMORV

©Villa Fano by AMORV

You bring artists into your design process early and advocate for fair compensation through the Fair Practice Code. What have you learned from working so closely with artists, and how do their perspectives change your own architectural thinking?

AMORV:Artists stretch the frame. They rewire how we see – and how we think. In architecture, there’s often pressure to resolve things – to make them clear, efficient, legible. But artists thrive in ambiguity. They’re fluent in nuance, in provocation, in intuition. Working with them early on keeps the design process open longer. It delays the moment of resolution – and that’s a gift.

Their way of seeing influences ours. They bring a sensitivity to rhythm, colour, gesture, and material that’s not about function, but presence. In the Foodvalley project, for instance, artist David Smeulders designed custom acoustic panels from recycled felt. His patterns – derived from natural systems – weren’t just decorative. They became a bridge between visual identity and spatial identity. Art and architecture spoke the same language. But it’s not just about aesthetics. It’s about ethics. We advocate for early involvement and fair compensation through the Fair Practice Code because we see artists as equal partners – not add-ons. Too often, they’re brought in at the end, expected to “fill a wall” or “add some colour.” We start with them. We co-create with them. And we pay them accordingly. In return, they shift our thinking. They remind us that a building is not just a machine or a diagram – it’s a cultural act. It’s something people feel. Artists help us build for that dimension – the one that escapes metrics, but defines experience.

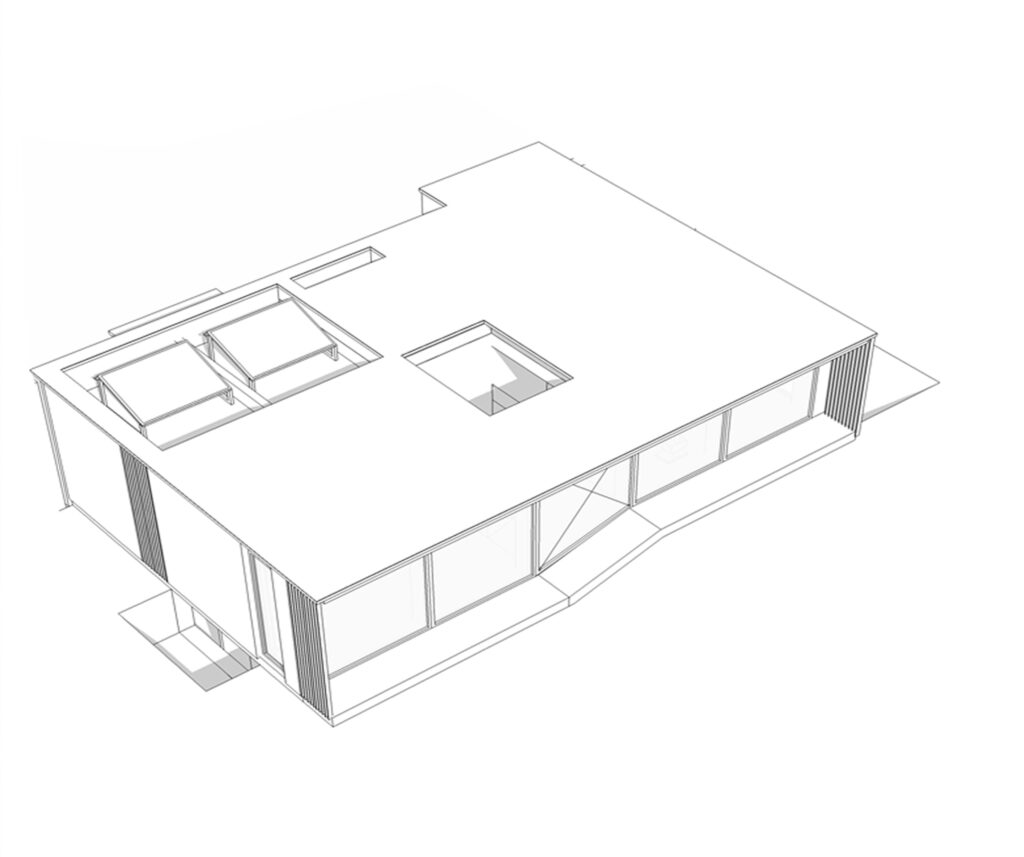

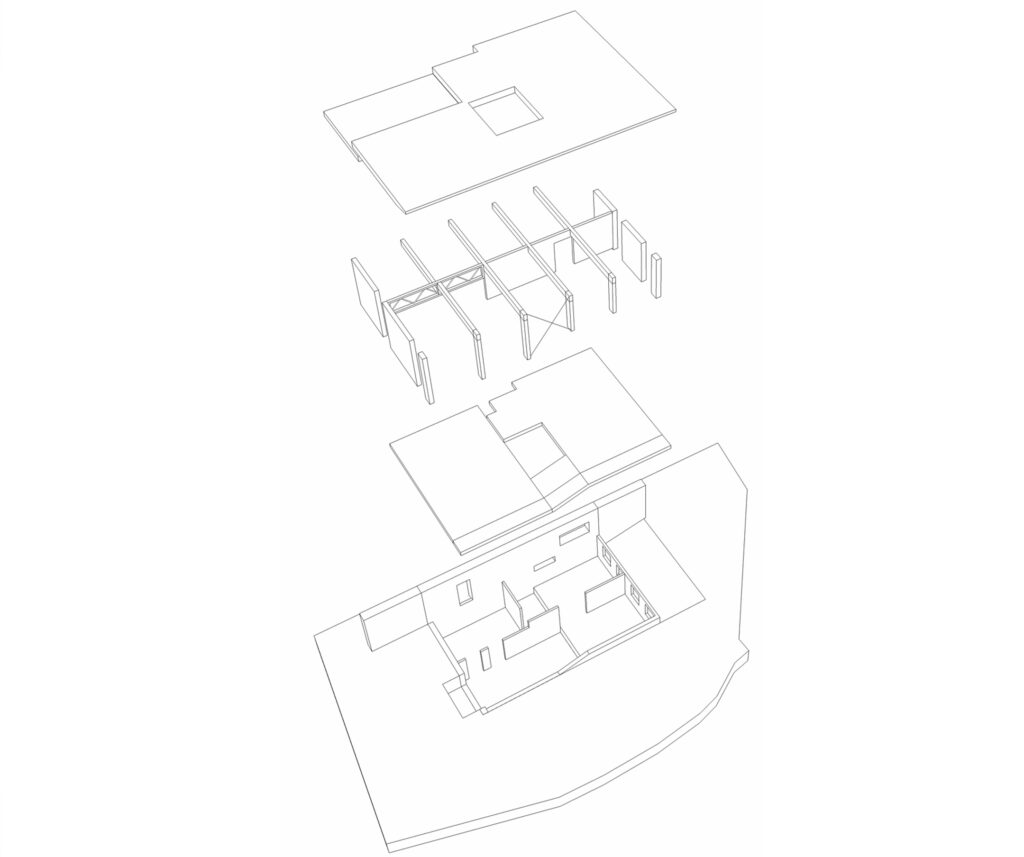

The brief called for a house that “whispers” rather than shouts. How do you translate such a poetic intention into practical design decisions—especially when it comes to form, materials, and the building’s presence in the landscape in The Dune House project?

AMORV: Whispering implies something hidden – something intimate and restrained. It’s not just about being quiet. It’s about humility. For The Dune House, we took that brief literally. We drew inspiration from Moroccan Riads – those almost invisible houses on the street, with closed façades that reveal nothing to the outside world. But once inside, they open into lush, majestic courtyards – places of light, air, and inward richness. That reversal became a guiding principle. We chose to embed the house into the dune, not to rise above it. From the street, it barely announces itself. No grand gesture. No need to perform. Because in an age of selfie sticks and compulsive social media expression, there’s something quietly radical about architectural modesty.

We returned the landscape to itself – a green roof restored the topography, and the architecture followed the contours rather than imposing on them. Light was brought in carefully, through daylight cylinders that carve quiet pools of sun into the interior. Materials were kept honest – drawn from what the site already offered. Sand-coloured concrete echoed the dunes. Pine wood spoke the language of the surrounding forest. Natural finishes, subtle textures, no gloss. This kind of restraint shifts the focus inward – from external display to internal life. From spectacle to spatiality. Instead of thinking about “space” as surface area, we thought in terms of spatial depth – light, sequence, atmosphere, silence. And in doing so, the building whispers. Not just out of modesty, but out of reverence – for the land, for the rhythm of living, for the possibility of stillness in architecture.

©The Dune House by AMORV

©The Dune House by AMORV

Looking ahead, in a world facing environmental, social, and cultural shifts, what do you believe is the most urgent role architecture must play—and how does your practice hope to answer that call?

AMORV: To reimagine what it means to build – and for whom.

Architecture today is too often reduced to economics, branding, or compliance. But the challenges we face – ecological collapse, social fragmentation, cultural amnesia – demand more than metrics. They ask for meaning. For reparation. For imagination. We believe the most urgent role of architecture now is to become a vessel for reconnection – with the land, with time, with each other. Not by building more, but by building differently. That means designing not for domination, but for participation. Not for permanence, but for adaptability. Not for visibility, but for presence. Buildings must no longer stand against nature, but grow with it – embedded, reciprocal, alive. At AMORV, we see architecture as part of a wider ecosystem of transformation. That’s why we work across scales – from zero-energy homes to system-thinking academies. That’s why we collaborate with artists, scientists, shamans, and gardeners. Not out of novelty, but out of necessity. Because the future cannot be built from within a single discipline. The built environment shapes not just how we live, but how we imagine life itself. Our hope is that through architecture – through space – we can reawaken a culture of care. One that listens before it speaks. One that builds not just for today’s needs, but for the dignity of future generations.

Not iconic. Not spectacular.

Just quietly, courageously essential.