At Fublis, our Design Dialogues series is dedicated to showcasing the innovative minds and creative journeys of architects and designers who are making a significant impact in the industry. Through in-depth conversations, we celebrate their achievements and explore their unique perspectives, offering invaluable insights that inspire both peers and emerging talent.

In this edition, we delve into the architectural philosophy of NAT OFFICE, a practice that emphasizes the dynamic relationship between architecture, city, and landscape to create distinctive project identities. NAT OFFICE’s approach to urban transformation, particularly in infrastructural projects such as seaports and railway stations, is rooted in a deep understanding of urban morphology and spatial flexibility. Their methodology integrates master planning, landscape design, and architectural interventions to establish a cohesive and sustainable urban fabric.

The firm’s ability to merge past and present is exemplified in the transformation of the former Hotel Cairoli into a contemporary photography center. This project underscores their expertise in adaptive reuse, striking a delicate balance between historical preservation and modern cultural functionality. The emphasis on architectural continuity ensures that spaces remain deeply connected to their urban surroundings, fostering inclusivity and community engagement.

NAT OFFICE’s exploration of spatial dynamics is further reflected in their work on HLBH, where movement through levels, voids, and full spaces creates a multidirectional user experience reminiscent of a Piranesi drawing. Their strategic use of transparency, adaptive reuse, and modular structures showcases a commitment to flexible, future-oriented design solutions that respond to evolving urban needs.

In this interview, NAT OFFICE shares insights into their design ethos, from integrating nature and technology in urban strategies to fostering a meaningful dialogue between materiality and human experience. Their vision extends beyond aesthetics, championing architecture as a living, evolving infrastructure that enriches both the built environment and its inhabitants.

Join us as we explore the pioneering ideas of NAT OFFICE and their transformative impact on contemporary architectural discourse.

NAT OFFICE emphasizes the relationship between architecture, city, and landscape to create unique identities for each project. Could you elaborate on how this philosophy influences your approach to urban transformation plans, particularly in seaports and railway stations?

Christian Gasparini: We worked many times on transformation and infrastructural plan and on mobility hub concept, in relation to the university researches and topics that I, as professor, leads at Polytechnic of Milan. This path flew in participation and awards to design competitions that leaded us to experimentation about typologies, morphologies and scales from masterplan and landscape to architecture and interior design.

Our approach works on the architectural scales as different layers to define a new urbanity, trying to reach the maximum density and flexibility of uses and the minimum consumption of territory. So Architecture becomes a medium between Nature and Technology, able to give a sense to the anthropic presence inside nature.

The urban strategies want to generate flexible interfaces: one of the first projects of NATOFFICE is the Masterplan of Valparaiso Port and City Centre in Chile, following the nomination as Unesco heritage of the city. The project regenerates the urban texture by using bulbs and fishnets to introduce a new translucent canopy on the main paths of the city centre, that became tridimensional by the geographical characters of the places (Valparaiso is shaped by the port and the hills all around the harbour) to reconnect the sea and the hills, the top and the bottom, one of the pacific most important port, its urban texture and the residential units on the hills, always watching the sea.

The transformation of the former Hotel Cairoli into a contemporary photography center creates a dialogue between past and present. What were the biggest architectural and conceptual challenges in repurposing this historical structure while ensuring it serves modern cultural needs in SFMG?

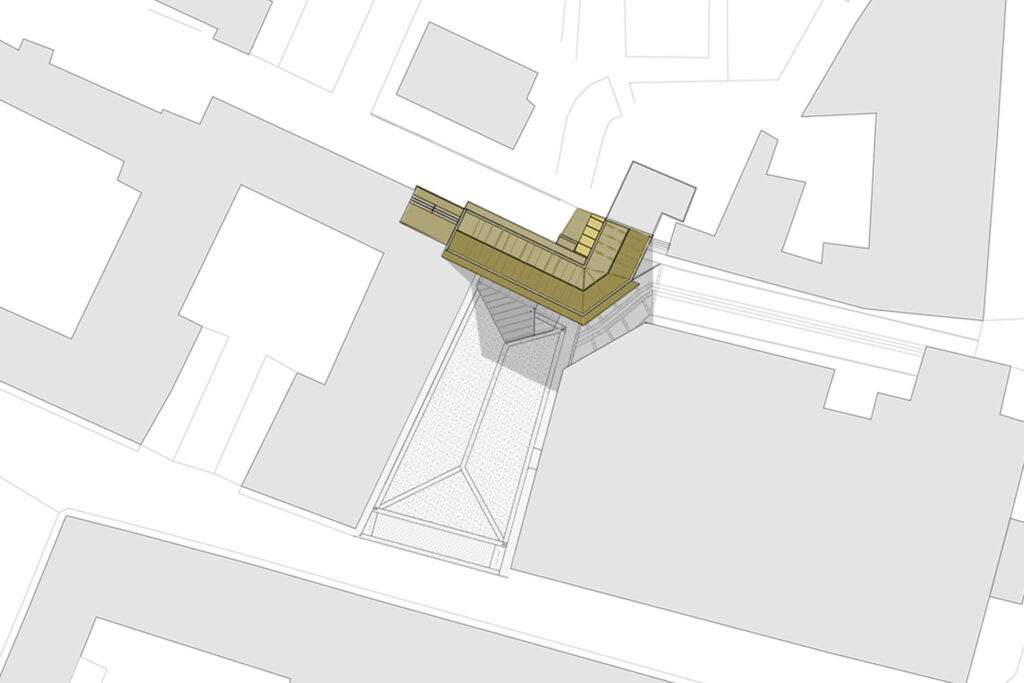

Christian Gasparini: The dialogue between past and present that this project seeks to establish is rooted in a reversal, a rollover – the desire to connect space through architecture rather than separate it, as it was in the past.

The former Hotel Cairoli, located on the lot, as well as the ancient medieval city walls topped by a walkway, served and confirmed an architectural “boundary” between the urbanized historic centre and the surrounding urban gardens. The challenge faced during the design process was precisely to create an architecture that could establish a seamless connection within the urban fabric of the historic centre, that would build a continuity across the city. The ability of citizens to identify themselves lies in the possibility of experiencing places by moving within them. In this way we put the observer, the tourist and the citizen at the centre of the scene and urban life.

Dedicated to the painter Marco Gerra, the European photography centre, itself was therefore conceived as a double-lens space (like the camera), able to host art, photography and culture but also to be viewed from the outside as an artistic insert in the city, an urban diaphragm, a foyer of passage, always following the rules of context.

©SFMG photography centre by Studio NAT OFFICE

©SFMG photography centre by Studio NAT OFFICE

©SFMG photography centre by Studio NAT OFFICE

The project emphasizes a “space-time dialectic between emptiness and fullness.” Could you elaborate on how the design physically manifests this idea and how it influences the way people interact with both the building and the adjacent XXV Aprile Square?

Christian Gasparini: Yes, we imagine the landscape, the city and the architecture as an identification system for the citizens. The cultural centre for photography and contemporary art, Marco Gerra, isn’t different, but rather represents the ideal approach to imagining a public space.

So, southward, Piazza XXV Aprile is an open esplanade, while, northward, Spalti di Santa Chiara, the ancient urban market and vegetable garden, is transformed into a meeting place, with seating all around. The building stands in the middle, like a ‘thick wall’, a threshold on both sides.

Thus the European Photography Centre is constituted as a façade, wall and backdrop of the square, but at the same time the wall is pierced, hollowed by the openings on the two long parallel sides, which transform it into an open diaphragm, defining a transparent ‘internal’ space: outside, from the square I look at the building and cross it with a view towards the Spalti di Santa Chiara; inside, the openings connect Piazza xxv aprile, the alley and the Spalti di Santa Chiara in a system of continuous space-time cross-references.

Emphasising the relationship between empty and full is the envelope of the architecture, whose transparency constitutes – together with the architectural element of the veranda – an invitation to passers-by to cross the city and gather places.

©SFMG photography centre by Studio NAT OFFICE

©SFMG photography centre by Studio NAT OFFICE

With a diverse portfolio ranging from cultural centers to temporary residences, how does NAT OFFICE ensure that each project maintains a balance between functionality and a strong architectural identity?

Christian Gasparini: For us contemporary architecture, intended as scientific and theoretical research, reflects on the ways in which built spaces correspond to existing places and their inhabitants. Architecture doesn’t research on the image in itself (self-referential architecture), it researches on the space as a generator of well-being. To do this, architecture focuses on the concepts of density, efficiency and flexibility.

NAT Office investigates landscape, city, architecture and interior space in order to understand design as the definition of precise grids of indeterminacy and architecture as the formal infrastructure allowing for multiple identities, open to different and unexpected uses and characters. If we imagine Architecture as an infrastructure, we can maintain and enhance a balance between functionality and identity by configuring spaces with variable density inside a latent structure, able to preserve the principles of organization and flows, and at the same time open to different uses.

©SFMG photography centre by Studio NAT OFFICE

©SFMG photography centre by Studio NAT OFFICE

The design of HLBH creates a fluid movement through levels, voids, and full spaces, allowing users to navigate in multiple directions, much like a Piranesi drawing. How did this concept influence spatial planning, and what strategies were used to ensure both functionality and spatial continuity?

Christian Gasparini: One of the main objectives of the project was to preserve the typological and morphological characteristics of the listed historic building complex. Consequently, the balance between solid and void elements on the façades, as well as key typological features such as the portico, have been carefully maintained. The character of the building was therefore that of a box in a box: the walls define an historical solid “box” that must not be changed, made by bricks, while the inner space of the barn is a completely empty box, which can be imagined as the main nave of a basilica.

The project want to maintain the building’s character by enhancing open and fluid spaces – inspired by Piranesi’s work – where levels dynamically overlap, creating double and triple height voids. This interplay of levels generates new enclosed surfaces that guarantee privacy and simultaneously delineate, like transparent glass, multiple perceptive juxtapositions.

The multifunctionality of the spaces allows for flexible configurations, enabling the building to function both as a residence and an office, blending and innovating the compositional dynamics of both typologies.

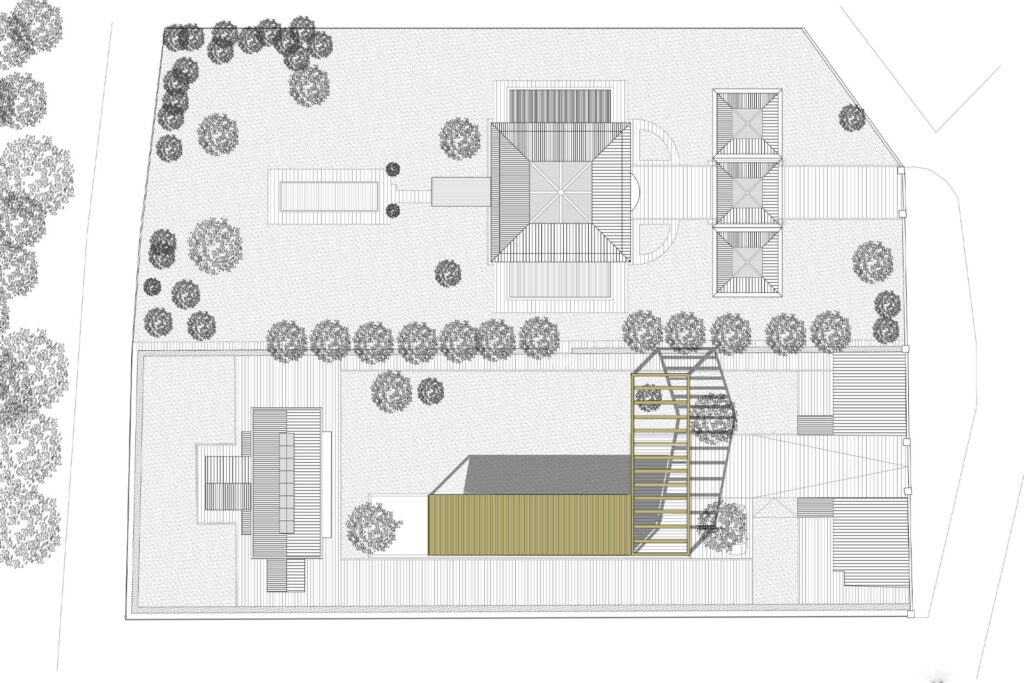

©HLBH by Studio NAT OFFICE

©HLBH by Studio NAT OFFICE

©HLBH by Studio NAT OFFICE

The project introduces a “fifth facade” by activating the roof with a terrace, skylights, and photovoltaic panels. Beyond sustainability, how does this element contribute to the overall architectural narrative and user experience of the space?

Christian Gasparini: The space is an architectural narrative, a “book” to to be read with the eyes, as Richard Sennett said in “The conscience of the eye”: thus on the upper floors, the piranesian movement of the staircase leads to the executive office-studio, which features a rooftop terrace seamlessly connected to the skylight of the winter garden, establishing itself as a true “fifth façade.” This space corresponds to the idea that “ancient” empty interior space filled with “new” glass cases, may manifest itself in the extrusion of the roof, not as built volume (impossible according to the rules for a listed building), but as subtracted volume: a terrace, a new open air space on the top. The inhabitants, like the workers can breathe and experience natural direct sunlight, even though they are inside a box, listed and closed on the perimetral walls.

©HLBH by Studio NAT OFFICE

©HLBH by Studio NAT OFFICE

©HLBH by Studio NAT OFFICE

Your practice explores modular structures designed for assembly and disassembly in various configurations. What inspired this focus, and how do you see it addressing contemporary challenges in urban planning and architecture?

Christian Gasparini: This is another theme really important in contemporary architecture, that flows at all the scales of the design strategies. We begun to work on it many years ago by participating and winning a mention in a competition organized by Italian and Chinese government on how develop innovative ideas-projects, material or immaterial, for the recovery, reinterpretation, updating and, if possible, reconfiguration of the collective image of the “Silk Road” as UNESCO World Heritage Site.

We conceived a light unit (silk-worm) able to be moved easily, that can be disassembled and reassembled in many shapes, able to mark the whole Silk Road, through its setting and reconfiguration in relation with local needs, generating a punctual dissemination of different elements divided for type: sight tower, caravanserai, linear edge, crossing bridge and for use: refreshment unit, bathroom, bedroom, info-point, exhibition space, shopping space.

They were conceived like knots of identification, appropriation and orienteering net from Rome and Venice to Xi an and Shangai. Contemporarily the cultural target was to generate signs by structural alluminium blocks (made in Italy) covered and coated by red tissue (chinese silk), that unify the landscape, constituting themselves as boundary stones of Roman Centuriatio or as disseminated fragments of the Chinese Wall, sequence of unique photograms of extremely differentiated landscapes, containing univocal contemporary signs.

So as for this project, even after we continued to work on the idea that temporary structures are changeable in time infrastructures, allowing diverse and generative appropriations by the people. In the landscape as in the city, this approach may become a strategy to extend and define a network of latent poles, that can prefigure new futures.

SAGM was designed to be more than just a workspace—it is a carefully crafted environment that interacts with light, nature, and creative process. How did you approach designing a space that not only serves practical needs but also inspires artistic creation?

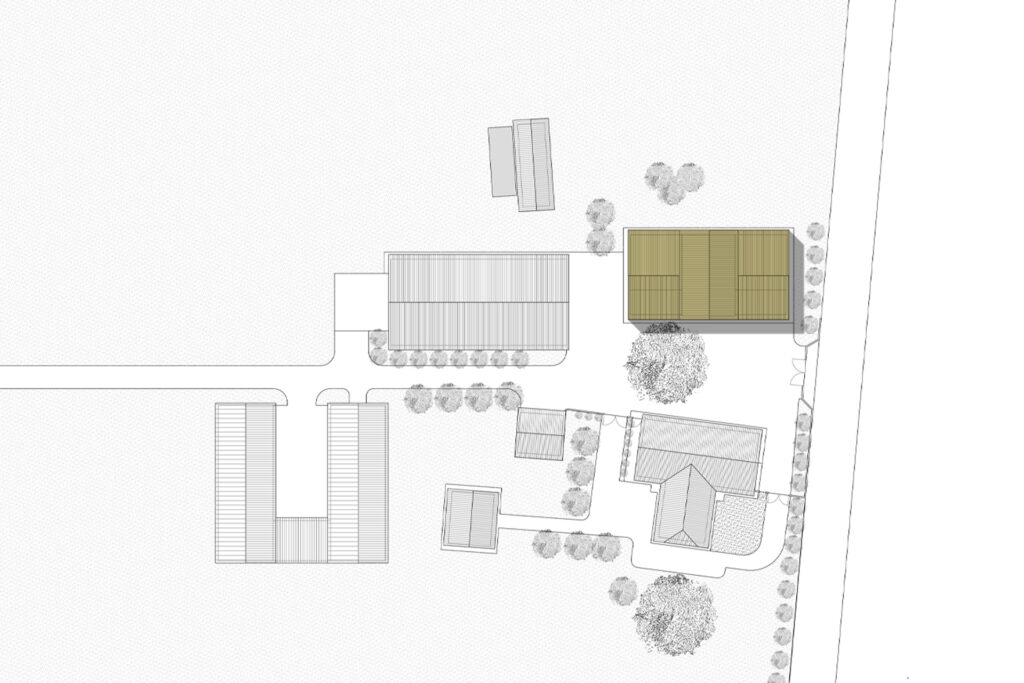

Christian Gasparini: Thank you very much for your acknowledgement: it is true that we experienced the idea that the space for a sculptor must inspire his creation process. We talked and discussed a lot with the client, but the most important thing is that we spent a whole day with him in the atelier and we realised, thanks to his movements, that there was a kind of ritual and working process in his work, always interconnected with the specific steps and actions for sculpting. We analysed the movements and paths that the sculptor must follow and trace in his activity and we conceived the building as a sequence of spaces, completely identified by the various phases of artistic production work.

It was therefore natural to imagine that the most important place, because the atelier is a sequence of places, should be the studio and the thinking room, the double-height nave, open to the light and capable of using shadow to define the work in a natural and immediate way, even on a sketch or a draft. Light, as the changing material of the sculpture, is brought in naturally, following the hours of night and day, and can be modulated by the movable curtains outside. Thus, the sculptor can feel and experience every day and hourly condition of the light. The sloping sky roof follows the structure but also enhances the inclination of the daily light input to reproduce the sunlight inside. Finally, this space, which contains a mezzanine as an office and bedroom for collaborators too, is conceived as the most flexible and switchable in terms of time and space thanks to a possible future extension and a double level.

©SAGM by Studio NAT OFFICE

©SAGM by Studio NAT OFFICE

©SAGM by Studio NAT OFFICE

The project emphasizes a strong connection between the atelier and the existing house through dimensions and proportions. Beyond physical alignment, how did you ensure that the architectural language of the new structure respects and enhances the character of the residence?

Christian Gasparini: As always for us, the place suggests measures and materials to connect ‘the new to the old’. Thus the physical alignment and positioning of the atelier define the measure of the building in context. The first connection we followed and wanted to enhance in the site was the perspective axis of the entrance gate on which the greenhouse was conceived: a strongly centred visual path, which we emphasised with the position of the atelier. The atelier respects the existing paved area at the entrance and extends a large, uncovered entrance porch on it, a kind of diaphragm to view the greenhouse. At the same time, the concrete platform at the back, where the sculptor models and carves the material, is another diaphragm between workspace and home/greenhouse.

The second connection (link) we thought to design was related to the structure and material of the greenhouse, which becomes the structure and material of the atelier. The wood, with its inclined shaped structure, reinforcing elements and anchoring details, uniformly defines the exterior of the volume and extends to the large open entrance porch. The structure, reduced to its essential limits, consists of a system of repeated close portals that create a rhythmic sequence, dividing a large double-height nave, opaque in its working space but fully lit on the two levels overlooking the park. The different finishing coatings, which are more related to the natural essence of wood and the size of the openings, configure a variation of the façade compared to the greenhouse.

©SAGM by Studio NAT OFFICE

©SAGM by Studio NAT OFFICE

Looking at NAT OFFICE’s body of work, there is a clear dialogue between architecture, materiality, and the way spaces are inhabited. As your firm continues to evolve, what is one architectural question or challenge that you are most eager to explore in your future projects?

Christian Gasparini: NAT Office is working and researching in two main directions: from one side we are trying to apply our process and approach to the scales of design, by studying smart territories, architectural masterplans, international competitions and residential projects, developing new urban strategies, based on the indeterminacy concept, from another for us architecture has to turn its procedural and compositional gaze to the concept of time, a concept that the contemporary virtual and technological world has made syncopated: an instantaneous shortened time, which structures fragments and not sequences, which has more to do with the idea of free time than with the idea of structured time of work, because in the fragment we find forms of immediate and absolute freedom.

Precisely for this reason the concept of free time has a lot to do with the spatial concept of “third place” (Ray Oldenburg), able to produce a network of physical-perceptual and cultural-creative relationships capable of configuring multiple real and virtual places.