Welcome to Design Dialogues, Fublis’ exclusive interview series dedicated to showcasing the innovative minds shaping architecture and design. In this series, we celebrate the achievements of visionaries who transform spaces and push the boundaries of creativity, offering invaluable insights to inspire peers and emerging talent alike.

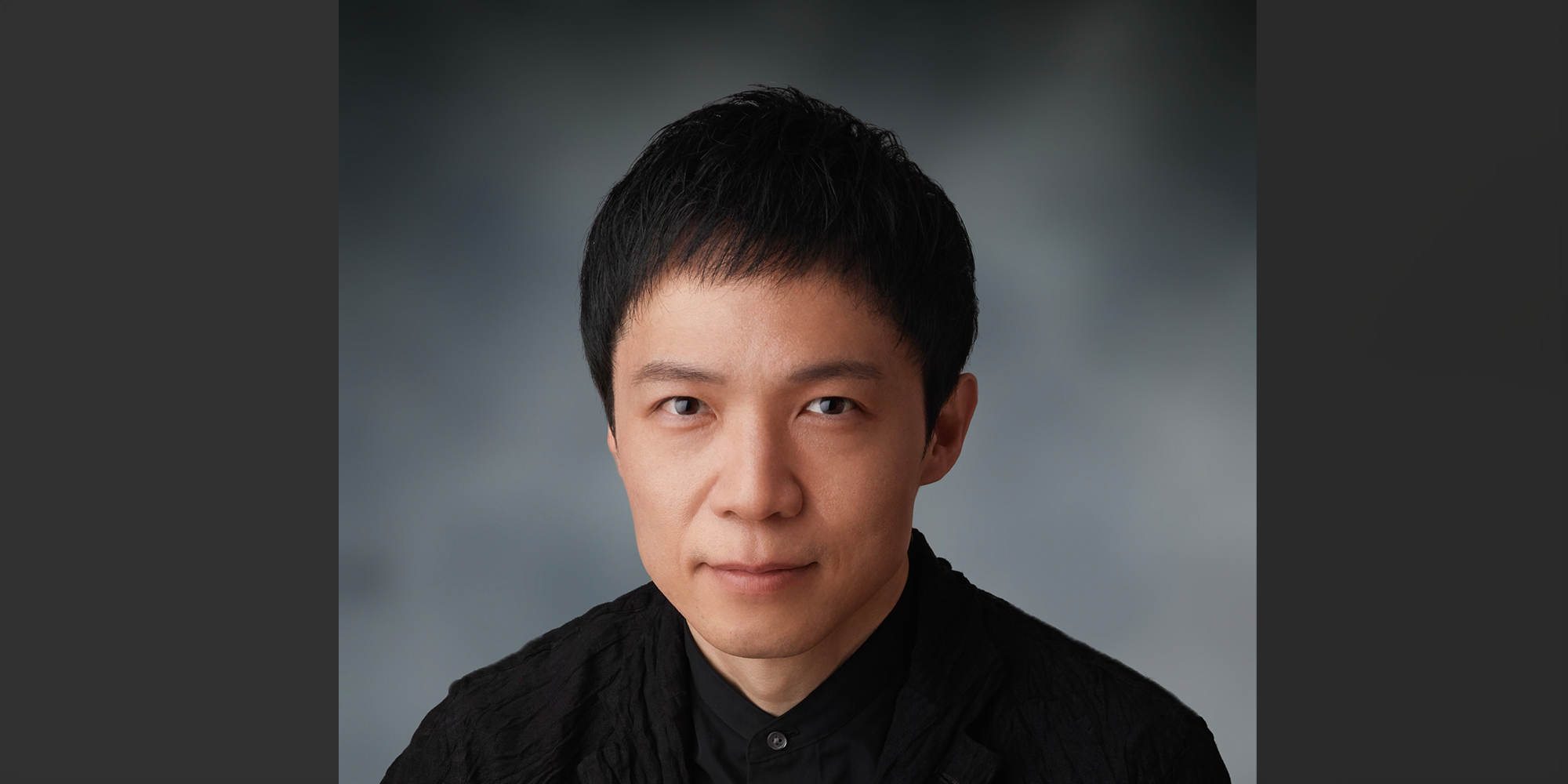

This edition features an inspiring conversation with SAKO Architects, a distinguished firm founded by Keiichiro SAKO in 2004. As the first Japanese-led architectural design practice established in China, SAKO Architects has delivered over 160 groundbreaking projects across five countries. From private residences to large-scale urban developments, their designs embody a harmonious blend of innovation, sustainability, and cultural context.

Explore how SAKO Architects’ unique philosophy of assigning thematic “manifestos” to each project has led to creations like the visually stunning Crystal in Jinan and the energy-efficient Squares in Tianshui. Through this interview, Keiichiro SAKO shares insights into his firm’s cross-cultural approach, transformative design ethos, and commitment to architecture as a medium for societal impact.

Dive into the full interview below to discover how SAKO Architects continues to redefine architectural innovation on a global scale.

Sako Architects emphasizes “transformable” and “diverse” solutions to meet varied project requirements. Could you share insights into the core ethos, design philosophy, and ideological principles that guide your studio?

Keiichiro Sako: In one word, it is “theme.” For every project, I assign a name using this theme in addition to the building’s official name.

I define a clear theme and ensure consistency in design, from the overall concept down to the smallest details. The theme varies with each project because the conditions for each are vastly different. Within these conditions, I carefully determine what approach will yield the best results.

For example, in my debut project CUBE TUBE, the theme was “form,” while for KALEIDOSCOPE, which used a significant amount of colored glass, the theme was “phenomenon.”

To me, the “theme” serves as a manifesto for the design challenge I take on with each project. Moving forward, I aim to continue exploring themes in design and taking on new challenges to expand the boundaries of architecture.

The design of Crystal in Jinan features “cracks” in the glass façade that flood the atrium with natural light while doubling as terraces. What inspired this innovative feature, and how did you balance its aesthetic appeal with functionality and structural considerations?

Keiichiro Sako: For my thesis, I studied “buildings with atriums designed by Japanese architects.” I wanted to analyze how multi-story atrium spaces integrate with single-story spaces and what effects they create.

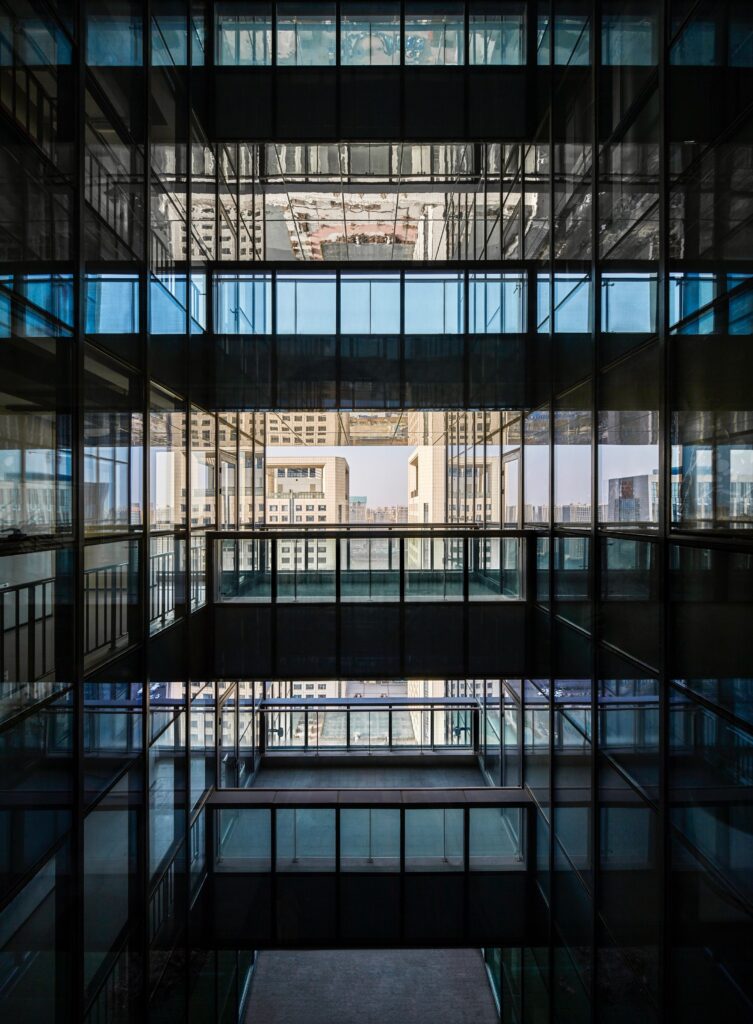

Atrium-based spatial compositions, which have always fascinated me, often appear in my projects. CRYSTAL is, to my knowledge, an unprecedented high-rise building with stacked atriums. Atriums create a sense of unity for users, but I believe the optimal number of levels for such spaces is five to seven. Beyond that, the connection between people on the first floor and the uppermost levels weakens. This led me to the idea of stacking four six-story atriums.

Each of the four atriums was designed with its own dedicated elevator bank and a unique entrance on the ground floor for the north, south, east, and west. In essence, it was like stacking four “six-story headquarters buildings” vertically. However, as the building neared completion, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the plans. Securing large tenants became difficult, and the layout had to be revised. The office spaces were subdivided, and the building now operates as a multi-tenant complex.

©Crystal In Jinan by Sako Architects

©Crystal In Jinan by Sako Architects

The atrium design, with its vertically stacked tiers and minimalist white space, creates an open and airy feel despite being enclosed. How did you approach mitigating the challenge of claustrophobia often associated with central atriums in large buildings?

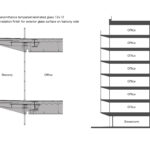

Keiichiro Sako: In office buildings, fully enclosed atriums can sometimes become overly quiet, creating an atmosphere where even normal conversations feel constrained. Introducing natural light through skylights is one way to address this sense of confinement, but this approach is impractical in skyscrapers.

Instead, we employed the operation of “carving out” the building’s volume, creating “cracks” in the glass mass. These cracks allow sunlight to enter the atrium from the sides, effectively alleviating the sense of enclosure and introducing natural light.

Additionally, we designed the atrium as a minimalist white space. This not only contrasts with the office areas but also utilizes the high reflectivity of white surfaces to diffuse sunlight deep into the atrium. These “cracks” also play a critical aesthetic role, making the building appear as a crystalline glass structure standing tall on the ground.

©Crystal In Jinan by Sako Architects

©Crystal In Jinan by Sako Architects

With its proximity to the high-speed rail station, Crystal in Jinan plays a prominent role in the urban fabric. How did its location and context influence the design, and how do you envision its contribution to the surrounding development zone?

Keiichiro Sako: The basic conditions, such as site area, floor area ratio, and height restrictions, naturally suggested the construction of twin towers sharing a common entrance hall. In fact, the surrounding buildings under similar conditions were all designed in this way.

However, in this project, we aimed to create an alternative form and offer it to the region, contributing to greater diversity on an urban scale.

When the “cracks” are illuminated at night, they evoke the image of a “rising dragon.” We believe that creating an outstanding landmark enhances the overall value of the region.

©Crystal In Jinan by Sako Architects

©Crystal In Jinan by Sako Architects

As the first architectural firm in China established by a Japanese architect, you have pioneered cross-cultural design practices. How has this unique position influenced your approach to architecture and collaboration?

Keiichiro Sako: I established my office in China 20 years ago, and last year marked its 20th anniversary. Over this period, I noticed significant differences between Japan and China in terms of economic development and architectural design practices. Early on, I realized that relying solely on conventional Japanese design methods would not lead to the best results. On the contrary, I came to believe that embracing these differences could enable the creation of architecture that would be impossible to achieve in Japan.

I created the term “Chinese Brand Architecture” to describe this approach and outlined three key elements—Speed, Scale, and Scope—that make it possible. Projects in China typically involve schedules that are three times faster (Speed), scales up to 100 times larger (Scale), and far broader responsibilities (Scope). By adapting to these conditions while fully utilizing my expertise as a Japanese architect, I aimed to create innovative designs.

For instance, in BOXES in Beijing and BUMPS in Beijing, I applied my unique design method, “Scaling Unit.” This approach involves setting a specific unit size that can be scaled up or down and combining multiple units to create the whole. In the former project, 400mm cubes were used as units, while in the latter, the unit was a two-story rectangular module. This method allowed me to successfully complete both a 300-square-meter interior project and a 100,000-square-meter large-scale mixed-use development.

In China, collaboration with local design firms is a regulatory requirement. Through my projects, I have found that simple and clear methods like “Scaling Unit” are highly effective in fostering successful collaborations.

The design of the library and day service center revolves around a square-plan mandala composition with a central courtyard in Squares in Tianshui. Could you share your inspiration for this design approach and how it enhances the experience for both the elderly and library users?

Keiichiro Sako: The name SQUARES carries a dual meaning: “plaza” and “square.” This day-care facility provides free meals daily to elderly individuals aged 80 and above, serving as a central hub for the village community.

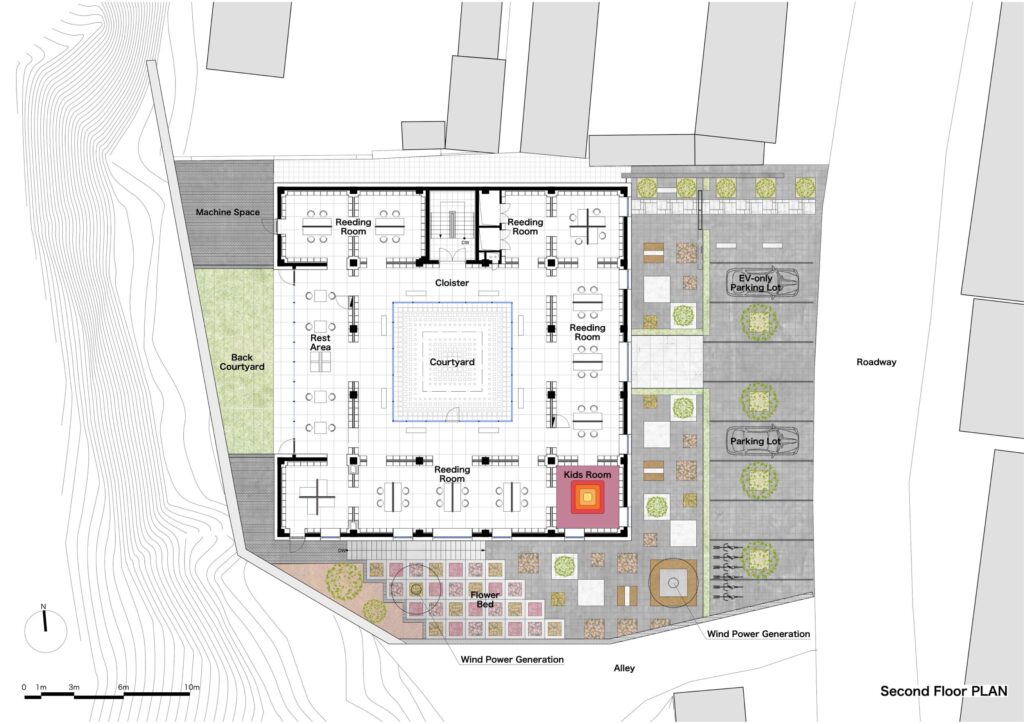

The second floor of the library features square-plan reading rooms and a courtyard arranged in a nested pattern, creating a layout reminiscent of a mandala. By incorporating the square motif consistently across different scales—from bookshelves and courtyard flooring to façade windows and the overall floor plan—we were able to achieve coherence and unity in the design.

©Squares In Tianshui by Sako Architects

©Squares In Tianshui by Sako Architects

©Squares In Tianshui by Sako Architects

©Squares In Tianshui by Sako Architects

Achieving a “Zero Carbon” certification and an impressive 166% energy self-sufficiency is a remarkable feat. What were the biggest challenges in integrating passive design and renewable energy into this project, and how did you overcome them?

Keiichiro Sako: High thermal insulation is essential to achieving zero carbon, which requires minimizing the size of openings. This library, located along a busy road with frequent vehicle and motorcycle traffic, also needed to ensure serenity as a library. Reducing the size of the openings naturally aligned with these insulation and acoustic requirements.

While the building is closed off externally, it fully opens inward to the central courtyard. To ensure thermal insulation, we used triple vacuum glass supported only at the top and bottom, without vertical frames. This approach maintained visual continuity between the courtyard and the cloister, creating a seamless connection between the two.

The courtyard canopy frames the sky, allowing users to feel the changing weather and shifting sunlight, providing an experience of natural phenomena. Through this design, we introduced a sense of “time” into an otherwise “enclosed space.”

Some buildings designed with zero-carbon goals in mind overly prioritize sustainability, often neglecting designs suited to their intended purpose. In this project, we emphasized creating a space that serves as a community hub—a “plaza” for the village—while also maintaining the spiritual depth embodied by the consistent use of the square motif across bookshelves, floor plans, and the façade. Throughout the process, we remained conscious not to let these design priorities be compromised in our pursuit of zero-carbon certification.

The “vertical rainbow” facade is a striking visual feature that reflects the company’s identity as a global paint brand. What was the inspiration behind using gradient-coated glass for the facade, and how does it convey the brand’s message?

Keiichiro Sako: Musashi Paint has embraced the corporate purpose of “enriching the world with color and function,” and we believed that embodying this purpose through architecture would deliver the strongest brand message.

To showcase their achievement of producing over 100,000 colors, we opted to use gradient-coated glass rather than single-colored glass. This allowed us to create fine gradations and express the concept of “infinite colors.” Additionally, to highlight their advanced technological capabilities, we collaborated with the company to develop a new type of paint specifically for outdoor glass applications.

VERTICAL RAINBOW became the ideal “theme” to integrate and symbolize these elements, serving as both an architectural statement and a representation of the company’s innovative spirit.

©Vertical Rainbow In Tokyo by Sako Architects

©Vertical Rainbow In Tokyo by Sako Architects

The facade blends changing skies with the colorful glass, almost like digital art. How did you ensure that the building remains equally captivating on cloudy days, and how do you think it contributes to the experience of passersby and the broader cityscape?

Keiichiro Sako: The colorful glass facade is in constant flux, never appearing the same at any moment. The color and angle of sunlight, the intensity of light, the colorful shadows cast by the glass, the reflections of clouds and the cityscape on the glass surface, and the contrast between the brightness inside and outside the building—all these parameters intertwine to create countless expressions.

VERTICAL RAINBOW brings a sense of festivity and vibrancy to a street otherwise lined with anonymous buildings. Office workers take pride in their building, the surrounding community welcomes it, and passersby are often moved by feelings of surprise and joy. It has already become a daily scene to see people stopping to photograph the building.

©Vertical Rainbow In Tokyo by Sako Architects

©Vertical Rainbow In Tokyo by Sako Architects

Reflecting on your remarkable journey in architecture, from establishing Sako Architects to leading diverse projects across multiple countries, what would you say has been your key takeaway about the role of architecture in shaping society today? Additionally, what advice would you give to emerging architects striving to make a meaningful impact in this ever-evolving field?

Keiichiro Sako: Over the past 20 years, SAKO Architects has primarily operated in two distinct environments: Japan, a mature society, and China, a rapidly developing nation. The architectural demands in each of these contexts were vastly different.

Initially, this distinct contrast was disorienting, but I soon came to see it as an opportunity. By strategically exploring ways to create new architecture within the given conditions, I found that these challenges stimulated my creativity. Adapting flexibly allowed me to discover diverse expressions that responded uniquely to each environment.

I believe that architecture crystallizes the culture, customs, systems, technologies, economies, and even emotions of the moment in which it is created. Even under identical conditions, there are various architectural responses that can emerge. Last year, my projects expanded further to India, Bangladesh, Uzbekistan, and Brazil. I am confident that these new contexts will continue to inspire more diverse and innovative solutions.

It is important for architects to remain conscious of how their work deeply influences the quality of people’s lives and to strive to create better architecture as a meaningful legacy for the future.

- Screenshot

- Screenshot