Welcome to Design Dialogues, Fublis’s dedicated series that delves into the innovative journeys of architects and designers shaping our world. In this feature, we present an inspiring conversation with the team at S. Ghosh & Associates, a practice deeply rooted in exploring the foundational essence of architecture. Their philosophy, informed by concepts like Louis Kahn’s “chapter zero,” strives to connect modern structures with primal architectural origins.

With a portfolio spanning influential projects like the Lucknow Airport Terminal, Java Ira Luxury Suites, and bold, competition-driven designs like the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, S. Ghosh & Associates demonstrates how each project can push boundaries while remaining sensitive to cultural and environmental contexts. In this discussion, they reflect on their approach to architecture as a means to serve both society and environment, emphasizing the importance of intuitive sustainability and community-driven urban spaces.

Through Design Dialogues, we aim to offer a thoughtful exploration of their design principles, ambitions, and reflections on India’s evolving architectural landscape. This conversation captures how S. Ghosh & Associates continuously seek to balance authenticity and innovation—reminding us that architecture, at its core, can be both a record of our heritage and a vision for our future.

Reflecting on your journey within the firm, which aspects of its legacy resonate most with you personally, and how do they influence your creative process today?

Sudipto Ghosh: You know that feeling when you dream of a place you’ve never been, but somehow it feels deeply familiar? I think we all carry these primal spaces in our subconscious. They’re pure, stripped of all the layers of pretence we’ve built up over time. No cultural baggage, no historical weight – just raw, honest architecture.This is exactly what Louis Kahn was getting at when he talked about “chapter zero” – that theoretical moment before anything was written about architecture, before we started theorizing and categorizing. It’s like trying to find that pure architectural DNA.

For the last fifty years, that’s been the driving force behind our office’s work. We’re constantly searching for these fundamental origins – what was the very first school like, before we had any preconceptions about what a school should be? What did the first workplace look like? Or that first shelter someone made from branches and leaves that became what we now call home?

It’s about pushing past all our architectural influences and training to tap into something more instinctive, more fundamental. We’re trying to uncover those spaces that resonate with our deepest architectural memories, the ones we didn’t even know we had.

Tell us a few projects where we are able to sense this return to the original moment or fundamental origin as you put it.

Sudipto Ghosh: You know, reaching that pure architectural state is way harder than it sounds. It happens best when you’re free from constraints – whether they’re client demands or even the pressures we put on ourselves chasing that “perfect” project.In my experience, these moments of clarity come in fragments. Often, they show up in projects that never make it off the paper – competition entries or proposals that clients found too bold. I see glimpses of it in my parents’ work, like what they did at the Dakshin Delhi Kalibari or the National GeophysicalResearch Institute in Hyderabad.

©Dakshin Delhi Kalibari

In my own work, I felt it most strongly while designing the Lucknow Airport Terminal. There were other projects too – the unbuilt Jindal Art Institute and Auditorium in Angul had that same quality. More recently, it emerged in our competition entry for the Incheon Museum Park in South Korea. And when we won that competition with Adjaye Associates for the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art – that really tapped into something fundamental, something that felt like we’d circled back to an architectural archetype.

©National Geophysical Research Institute

It’s interesting – these moments of architectural purity often come when we least expect them, and sometimes in projects that never see the light of day. But they’re crucial in shaping how we think about architecture.

©Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

©Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

©Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Can you share a project that is particularly meaningful to you? What made it special, and what impact did it have on the community or users?

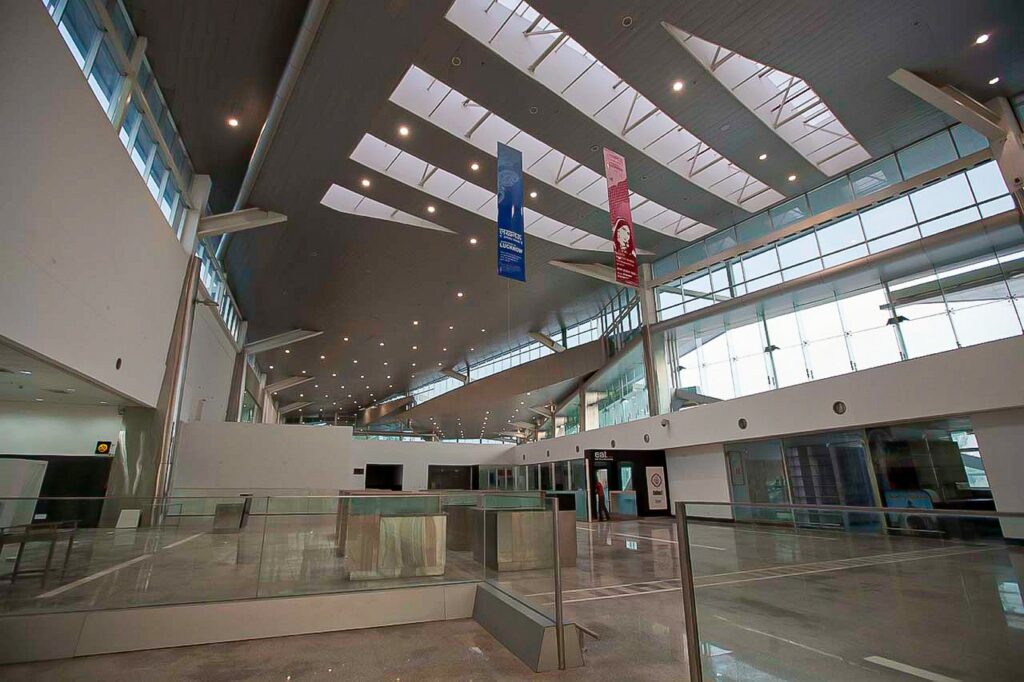

Sudipto Ghosh: The Lucknow Airport terminal project really stands out for me. I had just come back from the US after spending several years at Richard Meier and Partners, and somehow we managed to qualify for this Airports Authority of India competition. We’d never designed an airport before, but that’s what made it exciting – we could bring a fresh perspective to what an airport terminal could be.

I wanted to capture something deeply personal in this design. It’s funny how your experiences shape your work. I drew from my childhood memories of watching planes land, and even this vivid nightmare I once had about a plane crash. All these emotional connections found their way into the architecture.

Most airports end up being these massive sheds – just big warehouses with fancy granite floors and carpeting. We wanted to break away from that. The whole design tells the story of flight: the ceiling mirrors the underbelly of an aircraft, and there’s this dramatic moment where a roof wing literally crashes through the glass facade and enters the terminal space.Of course the entire structure is a giant origami paper plane.

What we were really after was creating a space that reminds people of what an incredible thing flying actually is. Think about it – you’re moving at 800 kilometres per hour through the air. That’s extraordinary. It’s one of humanity’s greatest technical achievements, and we wanted the architecture to capture that sense of wonder. If even a few people feel that when they walk through the terminal, I’d say we’ve done our job.

©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

Can you describe your design philosophy for the Java Ira Luxury Suites and how it reflects the unique cultural and geographical context of Odisha?

Sudipto Ghosh: I am really looking forward to the opening day of this building which should happen early in 2025. Presently it’s in finishing stage and only under construction images are available to show what I am about to say.

I am not sure if the hotel reflects the cultural context of Odisha, how you might imagine it relating to its wonderful temples or its crafts. But what’s interesting about Odisha is its natural character. Plants thrive effortlessly in that red soil and humid air, and daily life here really revolves around this constant interplay between indoor and outdoor spaces.

That’s what drove the hotel design – this exploration of the threshold between interior and landscape. Rather than just placing a building in its setting, we wanted to shape how people experience their surroundings. As you move through the hotel, you encounter different ways of seeing the landscape – sometimes it’s a wide-open panorama, other times it’s a carefully framed glimpse of nature. There’s this continuous dialogue between the built space and the world outside.

What happens is that walking through the hotel becomes more than just circulation – it turns into a journey where you’re discovering both the architecture and the landscape. The building becomes a way to read and understand its surroundings.

©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

How did you approach the integration of sustainable practices in the design of Java Ira Luxury Suites, and what specific features highlight this commitment?

Sudipto Ghosh: We have always taken a pretty straightforward approach to sustainability – it’s more about smart, intuitive choices than fancy tech solutions. If you get the basics right, like how you shape the building, which way it faces, and how you balance solid walls with openings while keeping in mind where the sun hits and how the wind flows – that’s really what determines your energy footprint.We were especially careful with the guest room windows. Since these spaces run AC pretty much all the time, we had to make absolutely sure no direct sunlight was hitting the glass. It’s simple but makes a huge difference.

Then there’s this idea that we firmly believe in about building longevity – when we use materials and details that make a building last longer, we’re basically spreading out its initial carbon cost over more years. So if we can make it last twice as long, we’re essentially cutting its environmental impact in half.

What really worked in our favour was having the steel plant right next door. We could use both recycled and new materials straight from there, which brought down our carbon footprint even more. Sometimes the simplest solutions are right in front of us.

©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

Reflecting on your experience with design competitions, is there a specific competition you participated in that you believe could have significantly changed the architectural landscape in India? If so, how?

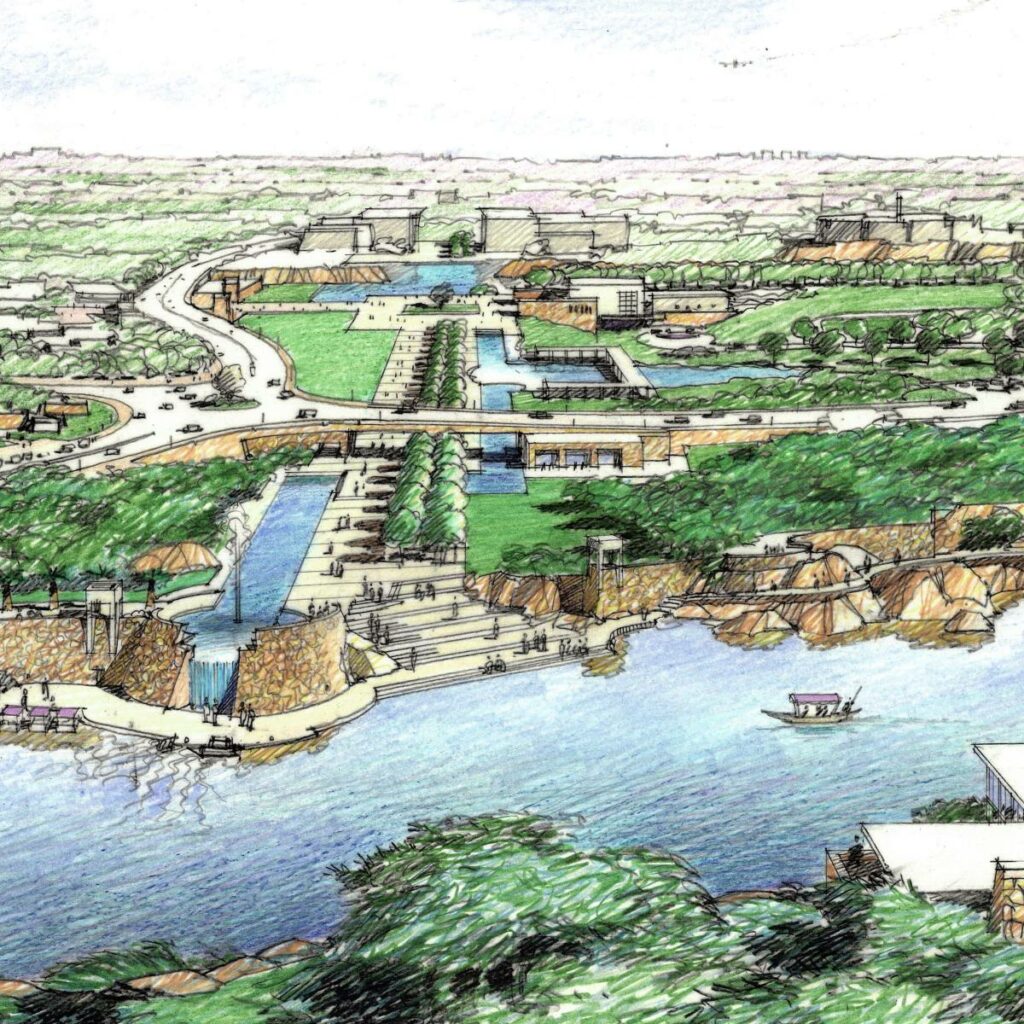

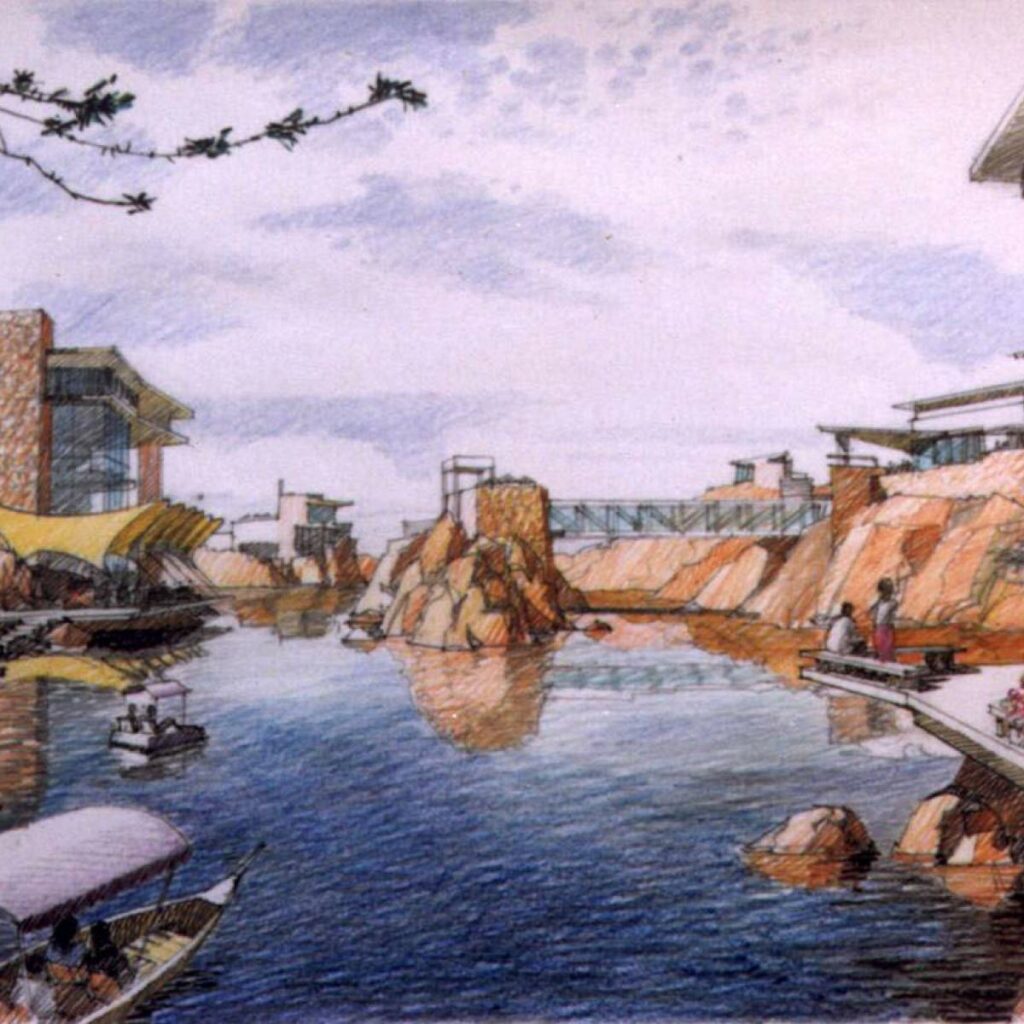

Sudipto Ghosh: We participated in this DDA competition for a hotels complex behind the Vasant Kunj malls in Delhi. The brief called for 9 hotels–basically what Aerocity is today– plus a convention centre, a golf course, and some significant institutions. What made the site interesting were these huge water-filled quarry pits from old stone mining operations. During monsoons, they’d fill up and keep the surrounding vegetation alive for months.We built our design around these rocky pits with their cool, sweet water. They’d created their own little ecosystem, and we wanted to work with that. The real challenge was dealing with hotels’ massive water and energy demands. We needed to figure out how to run this complex without depleting the local water table or depending on the power grid.

We made it through Stage 1, but then things got interesting – local residents filed a PIL, worried about water and traffic issues. Here’s what’s frustrating – instead of pushing us architects to solve these legitimate concerns, DDA just dropped the whole thing. I think we missed an opportunity there. Imagine if they’d said, “Okay, people are worried about these issues, let’s solve them.” It could have been a great example of public concerns actually improving a project.

It’s funny – now when I drive past Aerocity, I can’t help but think about what could have been if we’d taken those community concerns and turned them into design solutions for a rich and biodiverse city that still held enough built space to serve the needs of the capital.

©Hotels and Convention Centre Complex, New Delhi (A Competition Entry for Delhi Development Authority)

©Hotels and Convention Centre Complex, New Delhi (A Competition Entry for Delhi Development Authority)

How have you observed the evolution of recent architecture in India contributing to the betterment of society?

Sudipto Ghosh: Let’s get to the heart of this. When we talk about making society better, what are we really talking about? It’s about people breathing clean air and spending time with their families instead of being stuck in traffic. It’s about then spending that time we saved in pursuit of art, culture, and creative pursuits.

The solution starts with one radical shift – getting everyone onto public transport. Not just some people – everyone. We need such an extensive network of buses, trams, subways, and cycle paths that owning a personal vehicle becomes pointless. Then we build our workplaces, cultural centres, and commercial spaces around these transit nodes.

But here’s what’s critical – we need to sell this vision. Look at how Canada turned a maple leaf into a powerful national symbol. Why can’t Delhi create an equally compelling identity around its transport network, especially given its historic wheel and spokes plan?We actually created a comprehensive public transport map for the city and offered it to the government at no cost – a full year’s work. We’re still waiting for them to implement something truly transformative.

Think about it, when you see London, you immediately picture that iconic Underground logo and map, right? It’s not just a transit system – it’s become part of the city’s DNA. The Tube map is probably one of the most recognizable pieces of design in the world, and it shapes how people understand and navigate London.

Now imagine Delhi embracing its wheel-and-spoke layout as a powerful symbol. We could create a visual language that connects the ancient planning principles of the city with a modern transit network. The chakra, which is already deeply embedded in our cultural consciousness, could be reimagined as a symbol of urban mobility and efficiency.

This isn’t just about logos and maps – it’s about creating a new urban narrative. When people see this branding everywhere – on buses, metro stations, city signage – it becomes a constant reminder of what their city stands for. It builds pride in the public transport system and, more importantly, makes people feel part of something bigger.

Look at how cities like Copenhagen and Amsterdam have branded themselves around cycling culture. They’ve turned sustainable transport into part of their identity. Delhi, with its rich history and ambitious future, could do something even more powerful by connecting its historic planning principles with modern mobility solutions.

Only after we solve this fundamental issue can architects focus on what we do best – creating meaningful spaces for work and life. But first, we need to get people moving efficiently.

What trends do you believe might be harmful to the architectural identity of India?

Sudipto Ghosh:You know, this copy-paste culture in architecture really bothers me. We’ve got architects scrolling through Pinterest and design blogs, creating these collages of trendy images, and calling it design. What we end up with is this Frankenstein’s monster of a building – a bit from here, a piece from there, none of it really belonging together or to us.

Architecture isn’t about stitching together pretty pictures. It’s much deeper than that – it’s about how we understand our world and our place in it. When we just transplant images from somewhere else and try to make them work here, we’re not just creating inauthentic buildings. We’re actually changing ourselves, forcing our way of life to fit into someone else’s architectural vision.

When we copy a design from another context, we’re not just importing a look, we’re importing assumptions about how people should live, work, and interact. We’re essentially reshaping our identity to match these borrowed spaces instead of creating architecture that genuinely reflects who we are and how we live.

This isn’t just about aesthetics – it’s about cultural integrity and architectural honesty. Each project should grow from its own roots, its own context, its own purpose.

So how do we reverse this trend of Pinteresting Architecture?

Sudipto Ghosh: Its about defining beauty. This is what it comes down to. If you can define beauty for yourself, honestly, without messing around words and pictures, you will know that it is not what turns you on in those pictures on design blogs and Pinterest and Instagram. It may not even be pleasing to the eyes, but something that moves you profoundly. Not superficially like “oh that pink on that wall is so pretty” or “that twisty skyscraper is so cool” but something that leaves you stunned, like lightning splitting open a dark night followed by earth shattering thunder, or something that warms your heart like your grandmother’s wrinkled but kind face that speaks of a life well-lived.

Once you can define that for yourself, genuinely and without pretence, you’ll realize it has nothing to do with what’s trending online. Real architectural beauty might not even be conventionally pretty – but it should shake you, move you, warm you, or humble you. That’s when you know you’re onto something authentic.

It seems we have circled back to an idea of authenticity and an architecture that starts with Chapter Zero?What about the future and visions for that which we still do not know?

Sudipto Ghosh: Science fiction is my favourite genre of books. I do not think it is about alien and unfamiliar futures that are full of scientific inventions- all those flying cars and space colonies. It is more about imagining how a small change in our past can give us a completely different present. It’s like running these thought experiments: what if this one thing in our past had gone differently? How would that ripple through time and reshape our world? When you look at it that way, searching for Chapter Zero isn’t just about going backward to find some pure architectural origin. It’s actually a tool for imagining new possibilities.

It’s not about choosing between tradition and innovation – it’s about using our understanding of fundamentals to imagine what could be. Just like good sci-fi uses alternate histories to illuminate our present, good architecture can use its basic principles to show us new ways forward.

- ©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

- ©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

- ©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

- ©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

- ©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

- ©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

- ©Hotels and Convention Centre Complex, New Delhi (A Competition Entry for Delhi Development Authority)

- ©Hotels and Convention Centre Complex, New Delhi (A Competition Entry for Delhi Development Authority)

- ©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

- ©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

- ©Integrated Passenger Terminal at Lucknow Airport

- ©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

- ©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

- ©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha

- ©Java Ira Luxury Suites,Odisha