In this edition of Design Dialogues, we are pleased to feature ÔCO, a Lisbon-based architectural practice known for its pragmatic yet poetic approach to design. With a deep commitment to serving the community, ÔCO balances functionality and creative expression, ensuring that their work remains both practical and aesthetically compelling. Their projects, often shaped by budget constraints and regulatory limitations, reflect a remarkable ability to turn limitations into design opportunities, resulting in spaces that are contextually rooted and culturally resonant.

Through notable works such as the Lóios Gymnasium, Casa Caramão, and the SB44 Building, ÔCO consistently demonstrates a thoughtful approach to architecture—one that values utilitarian purpose while infusing spaces with meaning, emotion, and artistic identity. Their philosophy of embracing accidents, working iteratively, and collaborating closely with clients has resulted in designs that are both grounded in reality and elevated by creativity.

In this conversation, we explore ÔCO’s journey in navigating practical constraints, their philosophy of blending functionality with beauty, and the subtle yet profound ways in which their work transforms communities. This interview offers valuable insights into designing for everyday life while ensuring that architecture remains inspiring, human-centered, and culturally significant.

Your firm emphasizes interpreting dreams and connecting with clients on a deep level. How do you balance creative vision with practical constraints like budget, regulations, and technical requirements?

João Bucho: The balance between creativity, aesthetics, ethics, and utility is, in fact, the challenge in our profession. We understand that architecture is a service we provide to our clients to fulfill the practical need for a building—one that, as a secondary consideration, may be beautiful, unattractive, or simply unremarkable. It is in this second stage that art comes into play.

ÔCO began as a utilitarian architecture studio, focused on addressing the everyday needs of the community. Our first projects were legalizations of clandestine neighborhoods and unauthorized homes, as well as simple expansions to meet basic building needs, without major aesthetic ambitions. Once these primary needs were met and clients were satisfied with the guaranteed functionality, we then infused the building—and the way it was constructed—with artistic and poetic character.

It is worth noting that in Portugal, particularly within the community for whom we designed our early projects, there is a certain skepticism toward architecture. The myth persists that architecture exists only to create beautiful and expensive buildings. At one point, only 7% of the buildings constructed in Portugal were designed by architects. This is why our approach to architecture initially leaned more toward function—above all, it was utilitarian rather than intellectual or aesthetic.

The Lóios Gymnasium project focused on low-cost construction using primary materials as the final finish. What were the biggest challenges in achieving a sophisticated look while maintaining cost efficiency, and how did you overcome them?

João Bucho: The great challenge is to convince clients that an inexpensive material can have a sophisticated appearance, breaking preconceived notions and common assumptions. The materials themselves already possess all the qualities needed to achieve this—it is simply a matter of articulating and manipulating them correctly. Exposed metal structures painted in bold colors, using infrastructure elements to create a mechanical and technological aesthetic, or designing doors in a way that departs from traditional configurations can all contribute to this effect.

One example was the treatment of walls originally intended to be plastered and painted white. When we proposed a concrete-like finish, we were told there was no budget for it and that plastering and painting were the only options. So, we used the first layer of plaster as the final material—applying it as smoothly as possible—and replaced the paint with varnish. Essentially, these are choices that, in a typical scenario, might seem like cost-cutting measures or even mistakes. But when executed correctly and deliberately, they convey a sense of sophistication.

©Lóios Gymnasium by ÔCO

©Lóios Gymnasium by ÔCO

©Lóios Gymnasium by ÔCO

Reflecting on the project’s completion in 2016, how do you evaluate its impact on the community since then, and have there been any lessons learned that influenced your approach to subsequent community-focused projects?

João Bucho: For this particular building, we anticipated a high likelihood that its façades would soon be covered in graffiti. The pavilion is located in a social housing neighborhood where facades and communal areas are often degraded and vandalized. So, we decided to take the first step ourselves. We convinced the client to launch a competition for a graffiti artwork. We did not participate as judges—we wanted to minimize our influence in the selection process so that the client and the community would take full responsibility for the outcome. The artist was chosen, and the work was executed. Eight years later, the building remains free from vandalism.

©Lóios Gymnasium by ÔCO

©Lóios Gymnasium by ÔCO

©Lóios Gymnasium by ÔCO

Your ethos reflects a poetic exploration of emptiness and the in-between spaces. How does this philosophy influence your spatial organization and material choices in your architectural projects?

João Bucho: I believe that our design approach prioritizes functionality—ensuring that the practical needs of our clients are met first. Only after that do we consider the sensory impact of architecture, in terms of volume, light, and materials. However, we always seek to create an element of surprise in the spaces we design—something that, in a highly practical community like ours, might be perceived as bold.

©Lóios Gymnasium by ÔCO

©Lóios Gymnasium by ÔCO

Casa Caramão respects the neighborhood’s historical identity while introducing modern functionality. How did you strike a balance between preserving the architectural heritage and meeting the contemporary needs of the young couple?

João Bucho: Naturally, when designing buildings, we aim to respect and enhance not only the structures themselves but also their surroundings. In this case, the project was situated among a group of single-family homes built by the government in the 1940s to house poor families. This ensemble has a cohesive aesthetic and volumetric character that we sought to preserve and honor. While our initial design already aimed for this contextual harmony, the Lisbon City Council, which issues construction permits, raised the level of requirements and mandated that the exterior aesthetics and facade design remain unchanged. As a result, most of the innovations took place within the building rather than on its exterior. In essence, the “core” of the house was demolished to create open, multifunctional spaces with a structural system independent of the perimeter walls.

©Casa Caramão by ÔCO

©Casa Caramão by ÔCO

©Casa Caramão by ÔCO

You maintained continuity with the neighborhood’s aesthetic but introduced innovative interior features like the ‘reading cabinet’ and flexible compartmentalization. What inspired these creative solutions, and how did they contribute to the home’s functionality and character?

João Bucho: In some cases, the most creative and original functional solutions came from the clients themselves. Sometimes we provoke these ideas, playfully pushing boundaries, and clients collaborate. In this case, the clients were particularly open to such solutions.

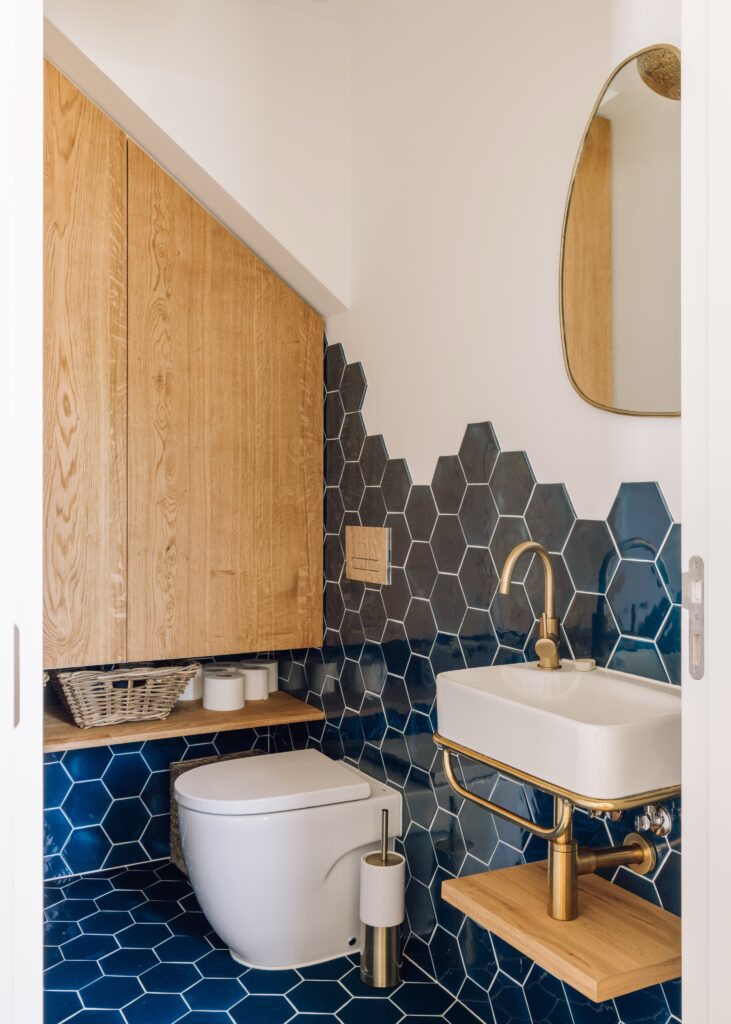

©Casa Caramão by ÔCO

©Casa Caramão by ÔCO

©Casa Caramão by ÔCO

You’ve described your design process as iterative, embracing accidents and evolving ideas. How do you foster a studio culture that encourages experimentation while maintaining architectural integrity and coherence?

João Bucho: At ÔCO, we often embrace mistakes as a tool to drive solutions and accelerate project development. This requires some initial context for clients so that they are not alarmed at the beginning of the process. Paradoxically, this approach increases our responsibility and rigor in achieving the final result. Mistakes are something we playfully take very seriously.

The SB44 Building preserves the historical identity of a 19th-century “Gaioleiro” structure while introducing modern interiors. How did you approach the challenge of maintaining the original facades while creating innovative, contemporary living spaces inside?

João Bucho: Once again, as with the Caramão House, this project involved the rehabilitation of a protected building under the Lisbon City Council’s jurisdiction. The city’s strict regulations for historic buildings impose significant constraints on interventions, particularly on façades. As a result, much of the creativity in Lisbon’s contemporary architecture—across all studios—has shifted toward interior design, while exteriors remain largely conservative. We focused more on designing the interiors, particularly common areas such as staircases and access points, while preserving the façades.

©SB44 Building by ÔCO

©SB44 Building by ÔCO

©SB44 Building by ÔCO

You chose traditional materials like pine flooring, Lioz stone, and patterned cement tiles to maintain the building’s historical character. How did you ensure these materials met modern performance standards, particularly in terms of durability and maintenance?

João Bucho: Durability, maintenance, and cost! For this building, we prioritized traditional, locally sourced materials for sustainability reasons (avoiding imported materials) and to enhance the property’s market value. The building was intended for sale to foreign buyers, who often value tradition and local character. Thus, we ruled out universal materials—such as ceramic tiles and laminate flooring—that could be found just as easily in Lisbon as anywhere else in the world. While these contemporary materials are often more durable and cost-effective, they do not meet the expectations of buyers seeking an authentic local experience.

©SB44 Building by ÔCO

©SB44 Building by ÔCO

Reflecting on your journey as an architectural firm, what philosophy or principle has consistently guided your design decisions, and how do you see it evolving to meet the challenges of the future built environment?

João Bucho: At ÔCO, our goal is to serve everyday people—we do not reject or selectively choose clients. If we can, along the way, create photogenic projects, unleash our creativity, push boundaries, and have fun collaborating with our clients, then we consider that a success.