At Fublis, our Design Dialogues series is dedicated to exploring the visionary work of architects and designers who are reshaping the built environment. Through in-depth conversations, we uncover the creative journeys, design philosophies, and groundbreaking projects that define contemporary architecture.

In this edition, we are honored to feature Nervegna Reed Architecture, a practice known for its innovative intersection of architecture, contemporary art, and urbanism. Their work challenges conventional boundaries, integrating bold spatial interventions with nuanced historical narratives. From the transformation of the Central Goldfields Art Gallery to the striking urban presence of the PEP cogeneration plant, Nervegna Reed Architecture’s designs redefine functionality, storytelling, and public engagement.

This conversation delves into their approach to balancing artistic expression with utility, the role of architecture in fostering dialogue, and the evolving landscape of Australian cities. With sustainability, heritage, and community at the core of their practice, Nervegna Reed Architecture continues to push the limits of architectural thought and form.

Join us as we explore their inspirations, challenges, and the future of design in a rapidly changing world.

Nervegna Reed Architecture’s work blends architecture with contemporary art and urbanism. How do you navigate the balance between functionality and artistic expression in your projects?

Toby Reed: This is a good question as it raises the point that we don’t really see functionality and artistic expression as mutually exclusive, or as being on opposite poles from each other. I think we need to be open minded about what exactly functionality is, and also realise that unexpected issues from brief, site or structure can often spark interesting creative resolutions.

The Central Goldfields Art Gallery project challenges conventional restoration by ‘surgically’ cutting through the building’s colonial fabric to reveal multiple narratives. How did this approach influence the way visitors experience the space, and what unexpected discoveries emerged during the process?

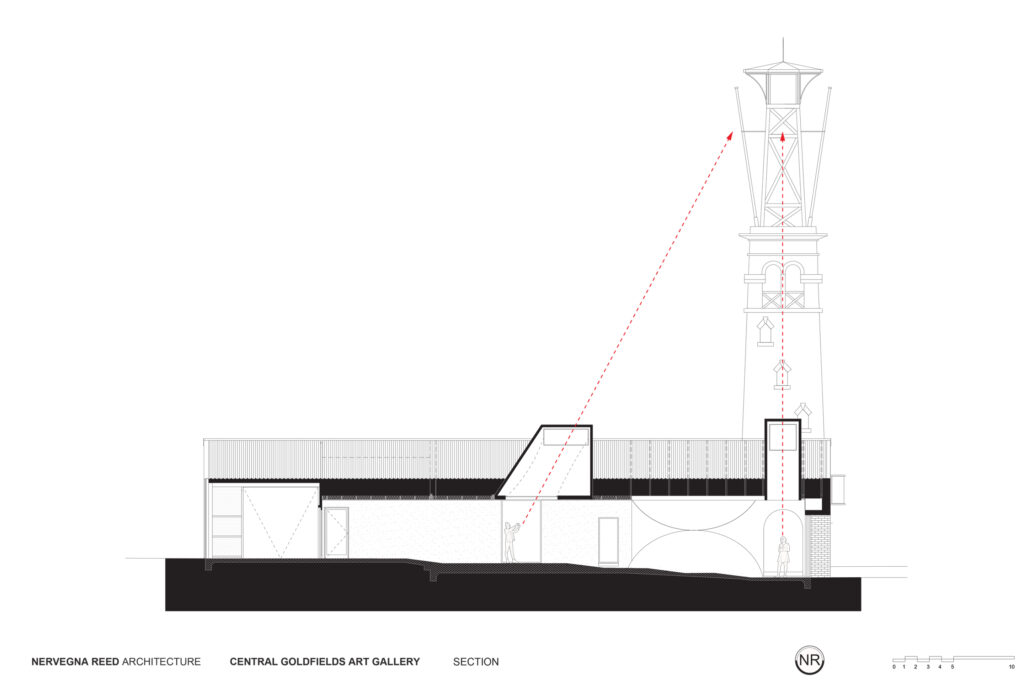

Toby Reed: From the earliest meeting with the clients for that project we discussed the collaboration between the Dja Dja Wurrung, who are the traditional owners of the land and the concept that the transformation of the old Victorian buildings needs to be open for everyone and not prioritising a single history, or version of history. So we decided not to “restore” the buildings to the exact state that they would have been in the 19th century. We developed a series of spatial cuts through the buildings which created spatial channels between the rooms with artworks and the Indigenous sculpture garden designed by the Dja Dja Wurrung Members. These are subtle spatial channels which visitors experience as they move through the building. A visitor could be standing looking at an artwork and will realise that they also have a view directly to the Indigenous Garden outside, which would not have happened with the closed Victorian architectural system. We also cut two spatial channels from inside the gallery, through the roof and aiming at views of the old Victorian fire tower. These views come as a pleasurable surprise to visitors, are spatial rather than form-driven, and are running against the Victorian spatial system. In these ways the building is deceptive as it seems quite simple but subtly draws the visitor into an unexpected experience.

©Central Goldfields Art Gallery by Nervegna Reed Architecture

©Central Goldfields Art Gallery by Nervegna Reed Architecture

©Central Goldfields Art Gallery by Nervegna Reed Architecture

The design introduces ‘displaced geometries’ and ‘spatial channels’ to disrupt the rigidity of the original colonial architecture. Can you share how these interventions contribute to the storytelling within the space?

Toby Reed: The spatial channels, as mentioned above, put the visitor in a subtle new relation with their reality. Any shift in the normal in architecture forces an awareness of reality (sometimes conscious, sometimes subconscious), our spatial reality and life in general. This in a very subtle way can provoke an openness for dialogue and storytelling. The displaced geometries work in a similar way. The circles in the Victorian arches are taken for granted. So, when we use the arch as a cutting device through the underside of the tower to the main gallery it forms a spatial corridor which feels like it could have always been there. In the foyer we needed a column and an edge to the ramp. So, we use the same circular geometry but split in half and rotated (the spit moon wall) for the side of the ramp and hidden column in the entry foyer. It formed a relation to the other geometry but is obviously composed in a way that seems wrong for Victorian architecture, which automatically starts a thought process in the visitor. The moon wall that connects the education room and the Indigenous Garden also reiterates this approach of the displaced geometry. When objects are displaced, they will encourage a shift in dialogue and storytelling. The success of the gallery in the community would attest to this.

©Central Goldfields Art Gallery by Nervegna Reed Architecture

©Central Goldfields Art Gallery by Nervegna Reed Architecture

©Central Goldfields Art Gallery by Nervegna Reed Architecture

Australia’s urban landscape is evolving rapidly. How do your designs respond to the challenges of density, heritage preservation, and contemporary city living?

Toby Reed: Australia’s urban landscape is evolving rapidly, and unfortunately with very little intelligent urban and architectural thought. The situation reminds me of Rem Koolhaas’ Junkspace essay. We do not have strong traditional cities like Europe that have evolved slowly. What we have is an infinite spread of new suburbia, often in the good farming land, and too many new bad quality high rises with not enough medium density in-between. Our buildings in some way comment on this situation as you can see with the PEP responding to a notion of the city as urban assemblage, and the Arrow Studio as displaced object in the landscape.

©Central Goldfields Art Gallery by Nervegna Reed Architecture

©Central Goldfields Art Gallery by Nervegna Reed Architecture

The PEP building is more than just an energy facility—it is a public landmark designed to spark discussion about sustainability. How did you balance the technical requirements of a cogeneration plant with the need to create an engaging and visually compelling urban space?

Toby Reed: The PEP being a cogeneration plant needed to be placed centrally in the city of Dandenong, as otherwise the efficiencies of the piped hot water would not work as well. Therefore, it could not be in a greenfield site outside town. It needed to be in the centre. So we had to make the building engaging to the public, who would likely never be able to go into the building while it is operating. I saw the metaphor of the television screen as a workable way to deal with the issue. The perforated screen has the ink blot splatter and the big switch and power points, working much like a screen which has a sliding scale between static and image. The building has been very popular, and the local youth sit around it at night as if it were a fire or TV in an external living room.

©PEP – Precinct Energy Project by Nervegna Reed Architecture

©PEP – Precinct Energy Project by Nervegna Reed Architecture

©PEP – Precinct Energy Project by Nervegna Reed Architecture

The use of super-graphics, perforated skins, and optical lighting patterns introduces an element of playfulness and abstraction to the project. What inspired this design language, and how do you see it shaping public interaction with the building?

Toby Reed: As mentioned, I saw the building as a type of three-dimensional screen where abstraction and image come into play. The artistic precedents are many, but the combines of Robert Rauschenberg were particularly influential on me. The giant splatter, which is formed by the variation in perforation sizes, is a nod to the earliest abstractions and the play of chance in the DADA works of Jean Arp, as well as Hermann Rorschach. I thought the guessing game that abstract shapes have always provoked (as we can see in the writings of Leonardo da Vinci and Alberti) would help provoke some urban interaction.

©PEP – Precinct Energy Project by Nervegna Reed Architecture

©PEP – Precinct Energy Project by Nervegna Reed Architecture

Sustainability is a growing priority in architecture. How does your firm integrate sustainable strategies beyond materials—such as in spatial planning, adaptive reuse, or community engagement?

Toby Reed: Wherever possible we encourage clients to go down the adaptive reuse route. This is the best way to stop the release of carbon into the atmosphere, as it reduces the production of new materials and reduces the destruction of old building fabric, both of which cause the release of carbon. It is important to see the existing urban fabric as a type of canvas upon which we work, not a tabula rasa. The concept of making minimal architectural manoeuvres to recontextualise space and form is integral and must replace the notion of the grand formal gesture.

The project Victorian Quaker Centre transforms a 1960s office building into a peaceful worship and community space. What were the biggest challenges in balancing the simplicity of Quaker philosophy with the architectural complexities of adaptive reuse?

Toby Reed: The Victorian Quaker Centre (sometimes known as the Melbourne Quaker Centre) was also a situation where we tried to make just a few spatial gestures to recontextualise the existing building. The hardest aspect to the project was getting consensus as according to Quaker philosophy, every member had to agree on the design. If there is one person who is unsure about something then a new path must be taken, as it could be a spiritual message. Once a plan was agreed by everyone, we did not change anything. The quaker belief in simplicity and consensus influenced the design, as did Quaker astrophysicist Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington. Some Quakers questioned the excessive expense of the coloured lights after construction, but once it was explained that the colour was free, everyone was happy.

©Victorian Quaker Centre by Nervegna Reed Architecture

©Victorian Quaker Centre by Nervegna Reed Architecture

©Victorian Quaker Centre by Nervegna Reed Architecture

The worship space is defined by shifting asymmetrical circles, creating a sense of fluidity and impermanence. How did this spatial strategy evolve, and how do you see it influencing the experience of those using the space?

Toby Reed: Quaker meetings are always in a circle. As we know, the panopticon prison was a Quaker design which was intended as an improvement to the inhumanity of incarceration. The original space had a column in the middle which destroyed the spatiality of the circular meeting. Melbourne has two orthogonal grids with a shift between them. The city grid and the wider inner suburban grid. The site for the VQC is in a triangular wedge between these two grids, the triangle being a wedge left over by the shift. The asymmetrical circles in the worship space denote the movement between these grids, while also referencing the proto-op art of Marcel Duchamp’s Anemic Cinema film from 1926. This attitude to the shifting of the site, the creation of place through circularity and the shifting of the geometries as a form of freedom of thought seemed like the right coalescence of ideas for the space. As all 80 Quaker members in the meeting agreed in the design presentation, we felt like we shouldn’t question it anymore.

©Victorian Quaker Centre by Nervegna Reed Architecture

©Victorian Quaker Centre by Nervegna Reed Architecture

If architecture is a reflection of its time, what story do you hope Nervegna Reed Architecture’s future projects will tell about the era we are shaping today?

Toby Reed: Although architecture is one of the most abstract arts, we hope that architecture can continue to create critical thought and debate through poetic spaces, forms, and materials. This is not easy, and we can only hope to contribute in a small way to a global situation. With our media saturated world, it is easy to lose touch with reality and we need to create spaces that bring people back to a sense of consciousness of reality and the positive possibilities.