At Fublis, our Design Dialogues series is dedicated to showcasing architects and designers who are shaping the future of the built environment through innovation, sustainability, and cultural sensitivity. In this edition, we sit down with Ishaq Rochman, an architect whose work seamlessly integrates environmental responsibility with community-driven design.

Rochman’s projects, such as Cibus City and Gap of Nusa, reflect a deep commitment to contextual analysis, biomimicry, and circular economy principles. His vision transcends traditional architecture, reimagining urban spaces as living ecosystems that harmonize nature, culture, and technology. Through his approach, he challenges conventional city planning and maritime architecture, proving that sustainable design can be both highly functional and deeply rooted in local identity.

In this conversation, Rochman shares his insights on polycentric urbanism, biophilic integration, and the evolving role of adaptive design in response to climate change and societal needs. He also discusses the delicate balance between tradition and modernity, demonstrating how architecture can be a tool for regeneration and cultural storytelling.

Join us as we explore his groundbreaking ideas and the transformative potential of architecture in designing a future where humans and nature thrive together.

Your projects emphasize a deep understanding of context and community needs. How do you approach the process of contextual analysis to ensure that your designs are both culturally relevant and environmentally responsive?

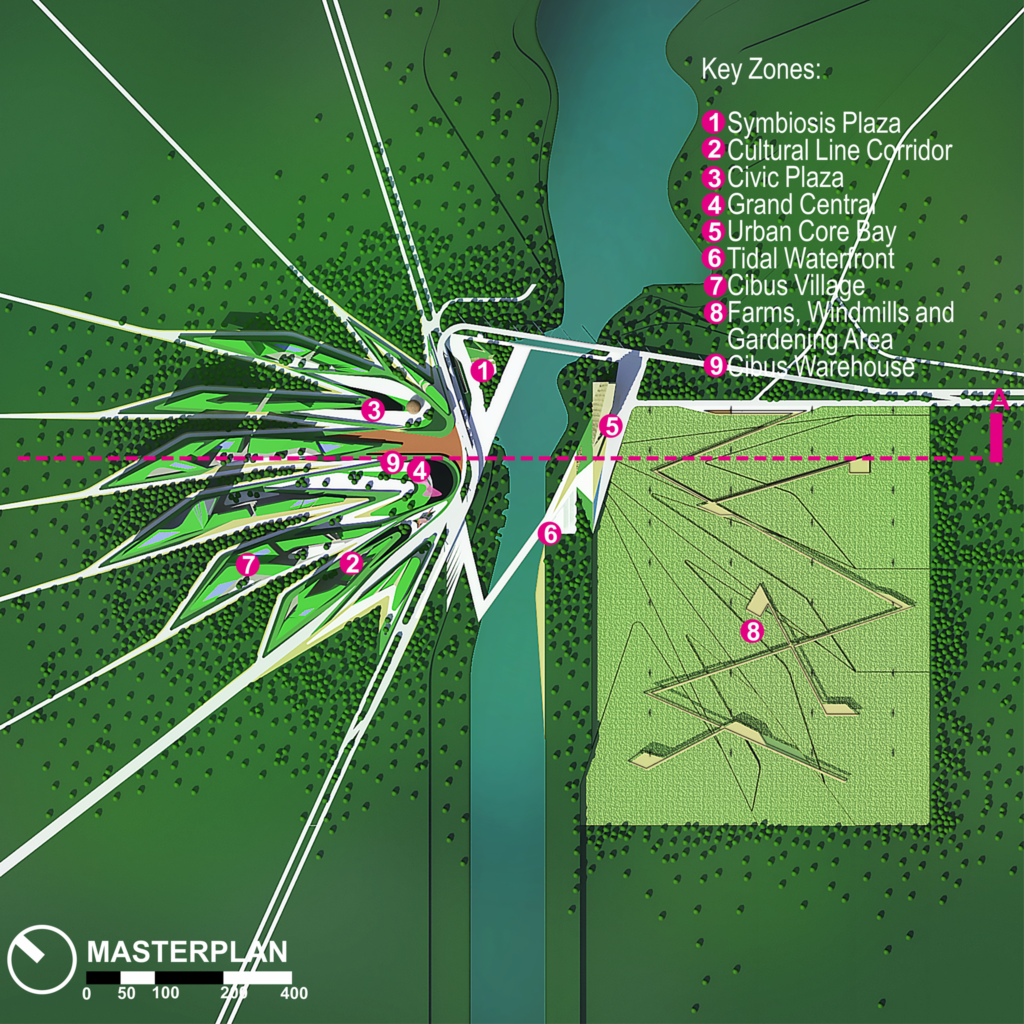

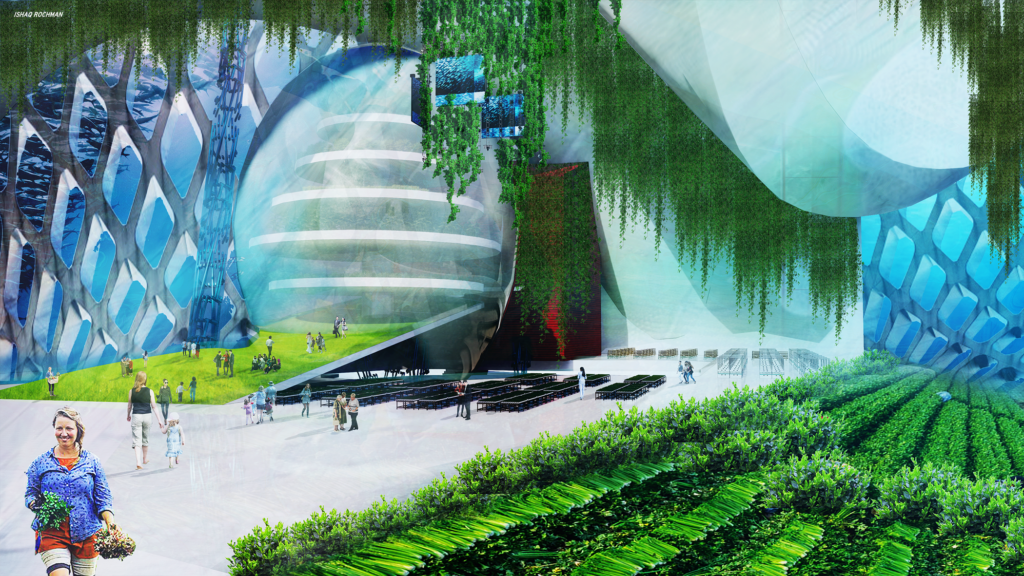

Ishaq Rochman: I believe architecture is not merely about constructing spaces, but about weaving connections between humans, nature, and culture. My vision is to create designs that unify sustainability, local identity, and innovation. Each project, such as Cibus City and Gap of Nusa, emerges from deep dialogue with environmental and community contexts. Cibus City was designed as an urban landscape integrating sustainable food systems, transforming cities into living ecosystems where agriculture and communities grow symbiotically. Meanwhile, Gap of Nusa serves as a bridge between cultural heritage and nature, crafting spaces that celebrate local wisdom without compromising progress.

My philosophy is rooted in circular economy principles—minimizing waste, restoring resources—and biophilic design through contemporary, which brings natural elements into human-made structures. For me, architecture must restore the balance between humans and nature, addressing not just energy efficiency but also psychological and spiritual sensitivity.

My work transcends physical buildings; it is about transformative experiences. I aim for every project to become a story that inspires ecological awareness, inviting communities to actively engage in building a sustainable future. By embracing cultural narratives and cutting-edge ecological practices, I am convinced architecture can be a tool to reweave our connection with the Earth and one another. This is my mission: to design a future where humans and nature thrive together, leaving a meaningful legacy for generations to come.

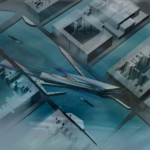

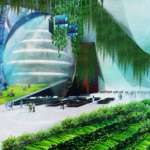

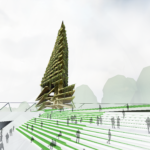

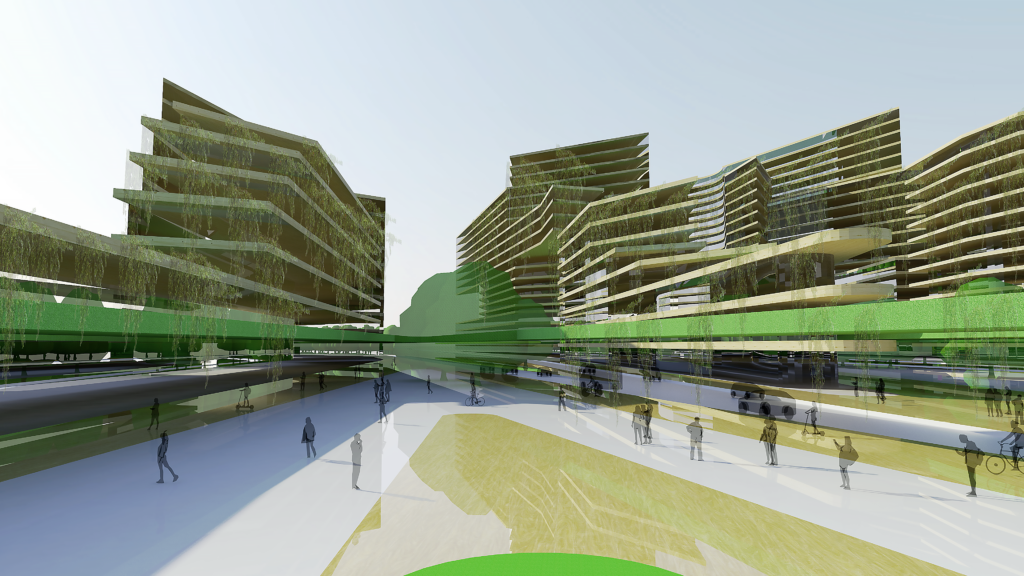

“Cibus City” is envisioned as a self-sustaining urban permaculture-based biophilic design. Can you elaborate on how you approached integrating natural ecosystems within an urban environment while ensuring functionality and modernity?

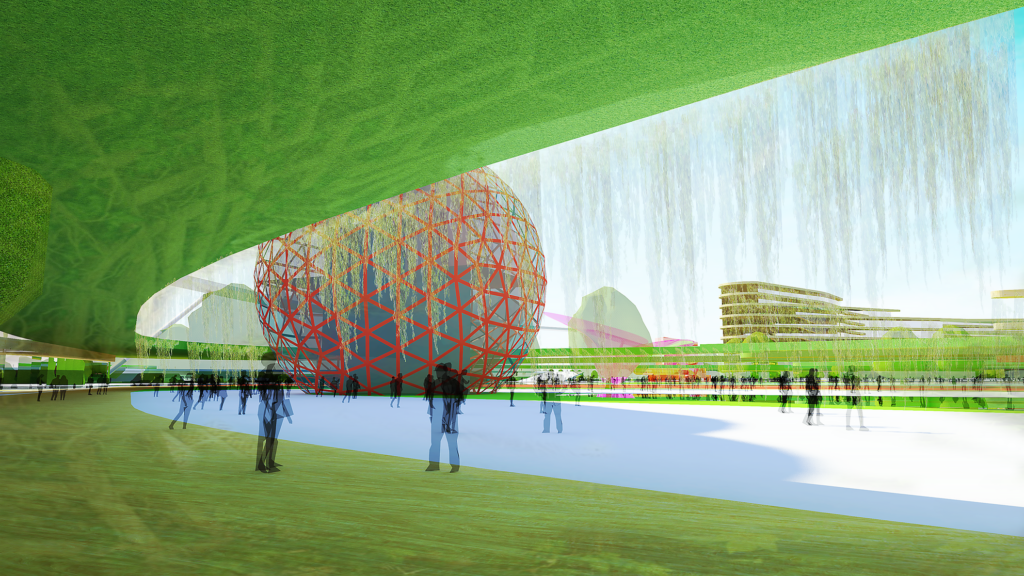

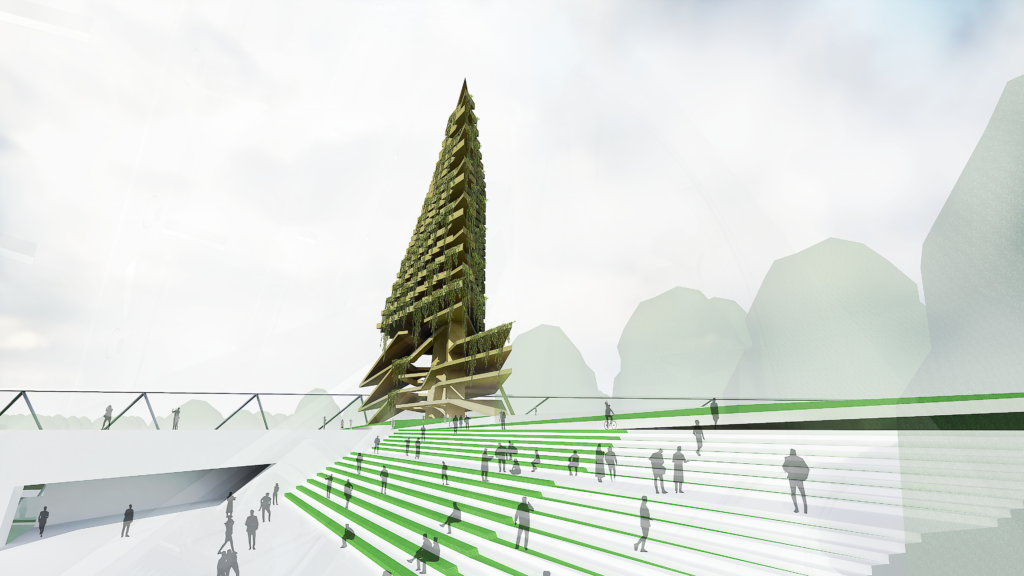

Ishaq Rochman: Cibus City was born from a simple yet radical question: How can cities nourish both people and the planet? My approach began by reimagining urban spaces as living ecosystems. I layered permaculture principles into the city’s DNA, creating a “foodscape” where agriculture isn’t an afterthought but the backbone of urban design. Rooftop farms, vertical food forests, and edible green corridors are woven into neighborhoods, ensuring fresh produce is steps away from residents. This isn’t just about aesthetics—it’s functional ecology.

To harmonize nature with modernity, I embedded biophilic design at every scale. Natural ventilation systems mimic forest airflow, while recycled rainwater cascades through terraced wetlands, cooling microclimates and filtering water organically. Materials like bamboo and mycelium-based composites connect structures to the region’s ecology, reducing carbon footprints without sacrificing contemporary aesthetics.

Functionality demanded innovation. Smart grids manage renewable energy from solar canopies, and AI-driven sensors monitor soil health in community gardens, ensuring food security. The circular economy is pivotal: organic waste becomes biogas for cooking, while agricultural byproducts feed 3D-printed compostable building materials.

But modernity isn’t just tech—it’s cultural relevance. Cibus City honors Bandung’s agrarian roots through communal balai (traditional pavilions) reimagined as hubs for urban farmers. By blending ancestral wisdom with cutting-edge systems, we’ve created a blueprint where cities don’t just sustain life—they regenerate it. Cibus City isn’t a utopia; it’s proof that when we design with nature, urban environments can be both hyper-functional and deeply humane.

©Cibus City by Ishaq Rochman

©Cibus City by Ishaq Rochman

©Cibus City by Ishaq Rochman

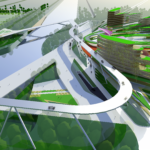

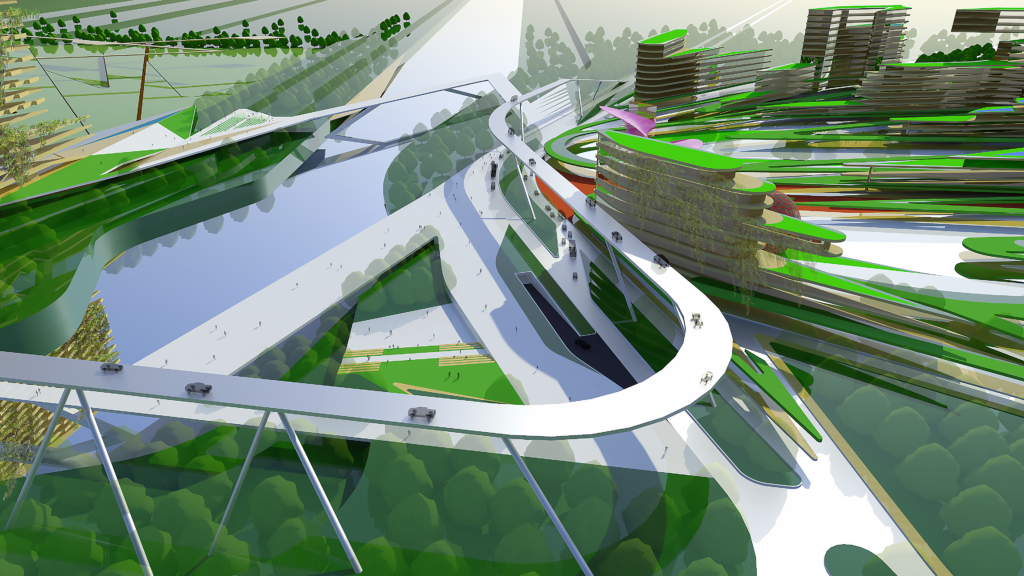

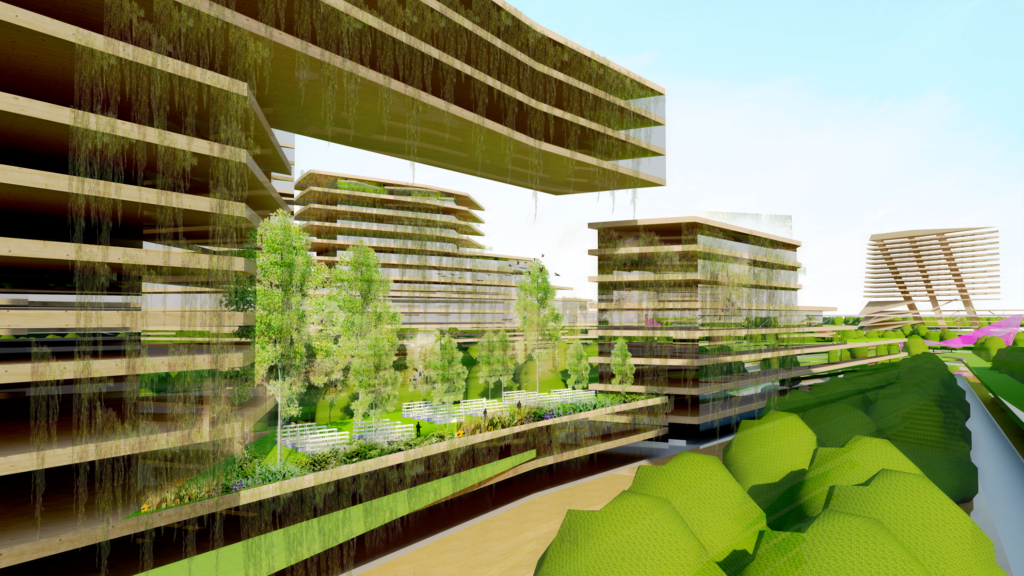

Your vision emphasizes polycentric development and sustainable mobility. What were the main challenges in designing a multi-core urban environment, and how did you address issues related to connectivity and accessibility?

Ishaq Rochman: Designing a polycentric urban environment like Cibus City required confronting two fundamental tensions: balancing decentralization with cohesion and reconciling human-scale mobility with ecological integrity. The core challenge lay in avoiding fragmentation—ensuring that multiple hubs could thrive independently while remaining synergistically connected.

1. Spatial Fragmentation vs. Ecological Continuity

In a polycentric model, there’s a risk of urban sprawl disrupting natural corridors. To address this, I redefined “connectivity” beyond transportation. Each hub in Cibus City is anchored by a green nucleus—a food forest, wetland, or community farm—that doubles as an ecological and social anchor. These nuclei are linked by biodiversity corridors that serve dual purposes: wildlife pathways and pedestrian/cycle greenways. For example, edible hedgerows along bike lanes not only provide shade and food but also stitch habitats together.

2. Equitable Accessibility in a Multi-Core System

A polycentric city can inadvertently create inequity if hubs lack equal access to resources. My solution was modular, layered mobility:

– Hyper-local networks: Walkable “15-minute neighborhoods” where daily needs (food, education, healthcare) are met within each hub

– Regional loops: Light rail and electric shuttle systems powered by renewables, connecting hubs via routes optimized by AI to reduce energy use

– Cultural connectivity: Pathways designed around historic trade routes or communal gathering patterns, ensuring mobility respects cultural memory (e.g., Gap of Nusa’s revived pilgrimage trails repurposed as scenic transit routes)

3. Resistance to Decentralization

Communities often associate “progress” with centralized density. To shift this mindset, I embedded shared-value infrastructure. For instance, decentralized waste-to-energy plants in each hub not only power local grids but also create jobs, turning residents into stakeholders of their hub’s sustainability. Similarly, mixed-use hubs blend housing, agro-industry, and cultural spaces, making self-sufficiency tangible.

4. Scalability Without Homogeneity

Polycentric design risks uniformity. In Cibus City, each hub’s identity emerged from its ecological and cultural niche. The “agricultural core” uses terraced rooftop farms echoing West Java’s sawah (rice terraces), while the “innovation core” integrates bamboo smart-grid pavilions. This diversity is unified through a circular resource network—compost from one hub fertilizes another’s farms, and reclaimed water systems link wetlands across nodes.

Ultimately, polycentricity isn’t just urban planning—it’s a philosophy of distributed resilience. By designing hubs as interconnected ecosystems rather than isolated units, we create cities that adapt, endure, and empower. The key was to make connectivity felt—not as a logistical chore, but as a lived experience of belonging to a larger, living organism.

©Cibus City by Ishaq Rochman

©Cibus City by Ishaq Rochman

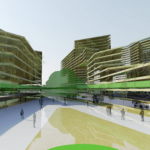

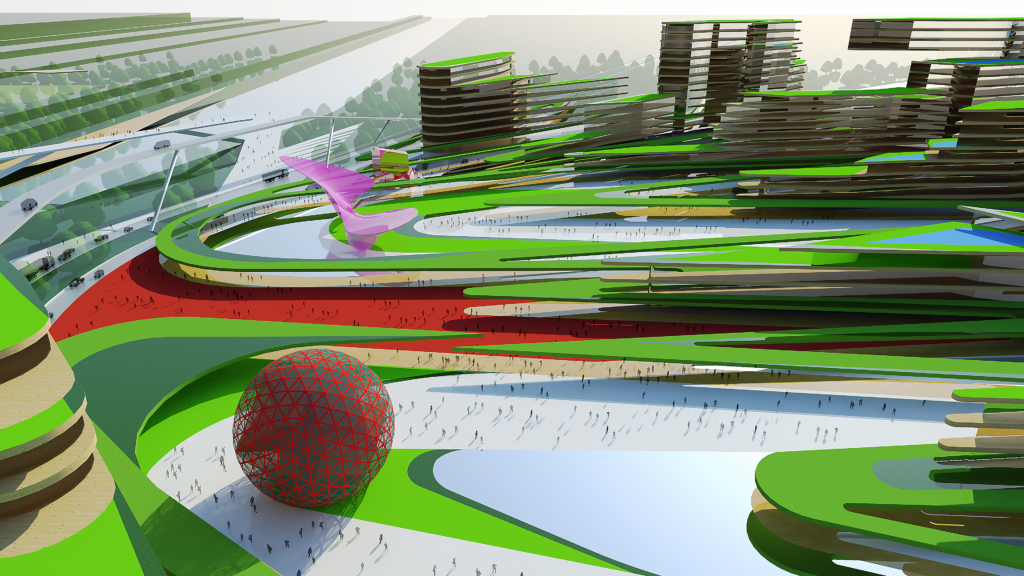

With a vision to repurpose and maximize efficiency through adaptive design, how do you foresee the evolution of “Cibus City” in response to future urban challenges and technological advancements?

Ishaq Rochman: Cibus City is designed not as a final solution, but as an evolving urban organism. Its vision is to create a city that “learns”—responding to new challenges through adaptive design, technology, and community participation.

1. Modular & Regenerative Infrastructure

The main structures of Cibus City are built on a plug-and-play principle. For example, residential blocks use bamboo frameworks that can be expanded or repurposed based on demographic needs. Rooftop farms currently growing vegetables could one day integrate next-generation organic solar panels or algae bioreactors for carbon capture. Materials like self-healing microbial concrete will replace conventional ones, ensuring climate resilience.

2. Collaborative Intelligence

The city will adopt community-driven AI. IoT sensors won’t just monitor air quality or crop yields but also gather data on residents’ consumption patterns to optimize food distribution. For instance, algorithms could redirect surplus chili from rooftop farms to local markets in need or predict the need for new wetlands as rainfall increases. Technology isn’t the ruler but a tool guided by the ecological ethics of the community.

3. Climate Adaptation as DNA

Facing rising temperatures and floods, Cibus City will evolve with dynamic green infrastructure. Constructed wetlands can expand as flood-absorbing “sponges,” while modular green canopies (with heat-tolerant plants) will grow along transit corridors. Water recycling systems will integrate hydroponic fog capture—technology that turns fog into irrigation, inspired by the wisdom of Java’s highlands.

4. Circular Economy 2.0

Organic waste won’t just become compost or biogas. I envision micro-factories in each hub using bioengineered enzymes to recycle plastics into construction materials or construction waste into hydroponic nutrients. Blockchain will track resource flows, ensuring transparency from farm to plate.

5. Culturally Rooted Innovation Hubs

Cibus City will become a living lab where tradition and technology mutually enrich each other. For example, Awan (traditional Sundanese rice barns) will be adapted into vertical storage with biogas-powered cooling, while the Seren Taun (harvest festival) becomes an urban agriculture innovation festival.

The Biggest Challenge? Ensuring this evolution remains inclusive. Technology must be balanced with ecological literacy among residents. I envision “garden schools” in each hub, where grandmothers and engineers co-design solutions.

Cibus City isn’t about a perfect future but about collective capacity to adapt. It will grow like a forest—organic, resilient, and always seeking new balance.

©Cibus City by Ishaq Rochman

©Cibus City by Ishaq Rochman

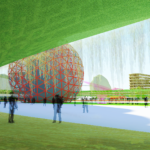

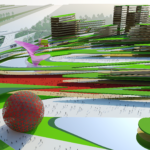

Your designs reflect a disciplined yet contemporary approach. Can you share how you navigate the tension between maintaining traditional values and embracing modern architectural trends?

Ishaq Rochman: My approach to contemporary design is about finding harmony between traditional values and modern architectural trends. I have always believed that tradition and innovation are not opposing forces—they can enrich one another when combined with sensitivity and creativity. However, achieving this balance is never simple. Every project becomes a dialogue, sometimes even a debate, between the past and the future.

1. Respecting Cultural Context

Before starting any project, I dedicate time to understanding the cultural and historical layers of a place. In the Gap of Nusa project, for instance, I spent weeks studying the traditional architecture

of Flores Island, particularly the distinctively curved roofs. I still remember the moment when a local artisan explained the significance of the curved roof. Later, I saw a grandmother selling food under a reimagined version of it, which reinforced its cultural importance for me.

At first glance, these forms seemed purely aesthetic, but through discussions with local artisans, I discovered that their design had been carefully developed to withstand strong coastal winds. The challenge was maintaining this wisdom while integrating modern efficiency. Collaborating with structural engineers, we reimagined the form using lightweight steel and glass, preserving its iconic silhouette while improving durability and sustainability. The result was a structure that remained deeply rooted in tradition yet embraced the advancements of contemporary architecture.

2. Adapting Tradition to Modern Functions

I see tradition as something dynamic, not rigid. In Cibus City, I was inspired by the balai—a traditional pavilion that serves as a communal hub for various activities, from morning meetings to midday markets and evening performances. My goal was to retain its essence while adapting it for urban life.

Situated over the water, the design reimagines the balai’s open and inviting nature with flexible spatial layouts and contemporary materials. This approach allows the space to seamlessly transform its function while preserving its cultural identity. The integration of local motifs into flooring and railings subtly reinforces its connection to tradition, ensuring that it remains familiar yet forward-thinking.

3. Creating a Dialogue Between Old and New

To me, design is a conversation—a continuous exchange between history and innovation. While working on Connecting Line in Amsterdam, I had to carefully balance modern intervention within a historically rich setting. The idea emerged after observing how the city’s canals shape its movement, inspiring the fluid form of the structure.

I was initially skeptical about using corten steel in Amsterdam, but seeing it blend naturally with the historic surroundings was truly satisfying. Rather than replicating the surrounding 17th- century architecture, I chose weathered corten steel, allowing it to age naturally and harmonize with the historic brick facades. At the base, smart glass adjusts its transparency in response to changing light conditions, creating a dynamic visual interplay throughout the day. Initially, some critics found the design too futuristic. But over time, it has become an integral part of the urban fabric, seamlessly blending into the cityscape while adding a new layer to its architectural narrative.

4. Flexibility for the Future

Architecture should evolve alongside the people who use it. This philosophy shaped my approach in Cibus City, where I designed modular structures that could be easily modified or repurposed.

One particular space was originally planned as a coworking hub, but during the pandemic, the community urgently needed a kitchen to distribute meals. Thanks to the modular design, we transformed the space within days—removing partitions, adjusting utilities, and integrating a community-driven food distribution system. As life returned to normal, the space evolved again into a youth learning center.

This adaptability ensures that architecture stays relevant—not just for today’s needs, but for the unexpected challenges of the future.

Ultimately, I strive for more than just preserving cultural heritage—I aim to make it a living part of the future. It’s about crafting spaces that feel both familiar and forward-looking, deeply rooted yet endlessly adaptable. True success in design isn’t measured by awards or aesthetics alone but by the everyday moments it fosters. Honestly, finding that balance is never easy—sometimes, you just have to trust the process.

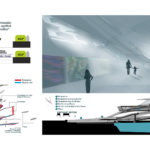

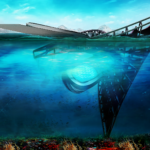

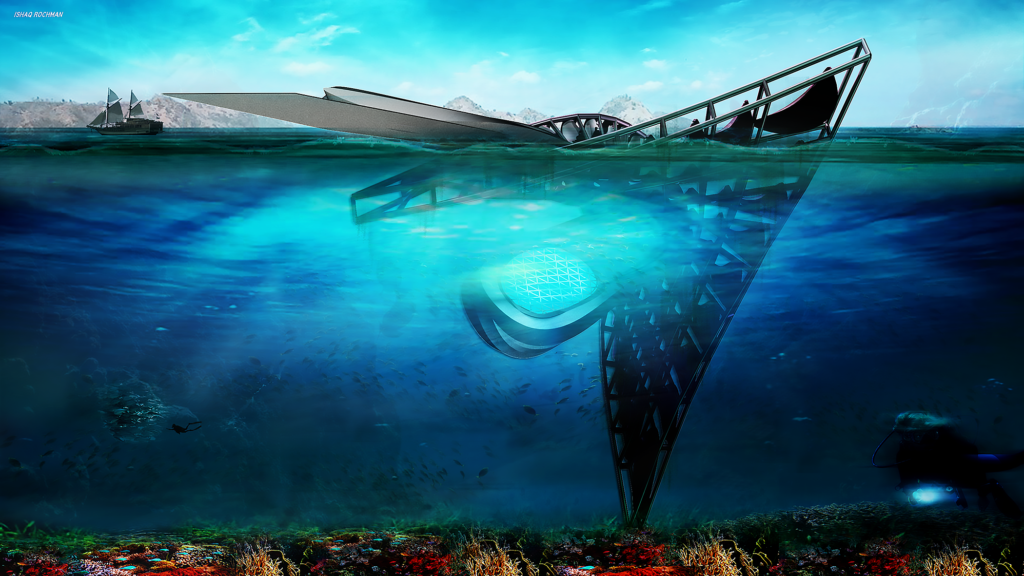

Gap of Nusa integrates a biomimetic approach inspired by chlorophyll cavities to enhance buoyancy and support underwater ecosystems. Could you elaborate on how this biomimicry influenced the overall design process and how it contributes to environmental harmony?

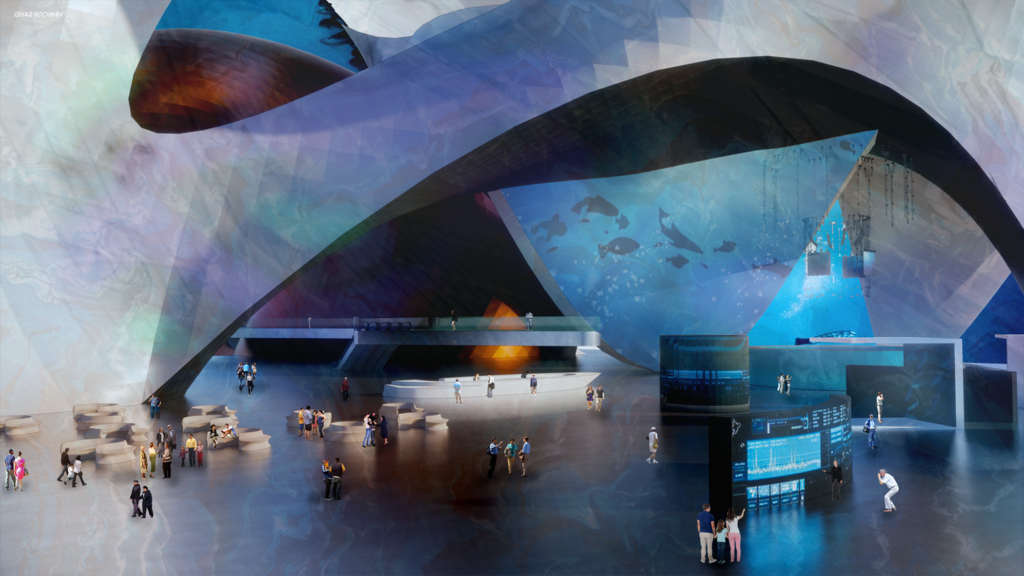

Ishaq Rochman: Gap of Nusa is a project inspired by the genius of nature, particularly the chlorophyll cavities in plants that enable them to float and photosynthesize efficiently. This biomimetic approach became the heart of the design, where underwater structures were crafted to mimic how natural cavities create buoyancy and support life.

The design process began by studying how chlorophyll cavities function—creating air pockets that not only stabilize the plant’s position in water but also serve as habitats for microorganisms. We applied this principle to the modular structures of Gap of Nusa, using geometries that maximize buoyancy while providing spaces for underwater ecosystems to thrive. Each module was designed as an “artificial reef” resembling natural formations, allowing marine biota like corals, fish, and microbes to attach and grow.

The contribution to environmental harmony is evident in two main aspects:

1. Ecosystem Restoration: The structure functions as a breeding ground for marine life, helping to restore biodiversity in the waters of Flores, which are threatened by climate change and human activities

2. Human-Nature Symbiosis: Gap of Nusa is also designed as a sustainable educational and tourism space. Visitors can dive and witness firsthand how this biomimetic design supports marine life, fostering awareness of the importance of protecting underwater ecosystems

By combining nature’s intelligence with human innovation, Gap of Nusa is not just infrastructure but a symbol of how we can live in harmony with nature.

©Gap Of NUSA by Ishaq Rochman

©Gap Of NUSA by Ishaq Rochman

One of the key aspects of this project is the application of a circular economy model. Can you share some of the challenges you faced in incorporating this model into maritime architecture, and how did you overcome them to maintain both functionality and sustainability?

Ishaq Rochman: Implementing a circular economy model in maritime architecture like Gap of Nusa presented several significant challenges. First, sourcing sustainable local materials. Many conventional materials used in underwater construction, such as concrete and metals, have high carbon footprints and are difficult to recycle. To address this, we turned to alternative materials like natural fiber composites (e.g., water-resistant bamboo) and eco-friendly concrete embedded with microbes that self-heal cracks.

Second, logistics and energy in construction. Building at sea requires substantial energy for transportation and installation. We overcame this by designing prefabricated modules that could be produced on land and assembled on-site, reducing energy needs and waste. Additionally, we utilized renewable energy sources like floating solar panels and tidal turbines to power construction operations.

Third, integration with local ecosystems. The biggest challenge was ensuring the structures didn’t disrupt existing marine life. Our biomimetic design mimics natural coral and chlorophyll cavity forms, allowing marine organisms to use them as habitats. Furthermore, construction waste was repurposed into substrates for coral growth, creating a circular cycle that supports ecology.

Finally, community involvement. A circular economy isn’t just about materials—it’s about people. We collaborated with local fishermen and coastal communities to manage and maintain these structures, while also creating new jobs in sustainable tourism and ecosystem restoration.

Through this approach, Gap of Nusa not only functions as infrastructure but also serves as a tangible example of how circular economy principles can be applied to sustainable maritime architecture.

©Gap Of NUSA by Ishaq Rochman

©Gap Of NUSA by Ishaq Rochman

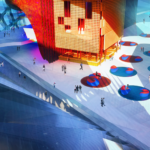

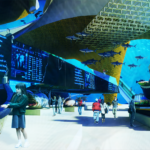

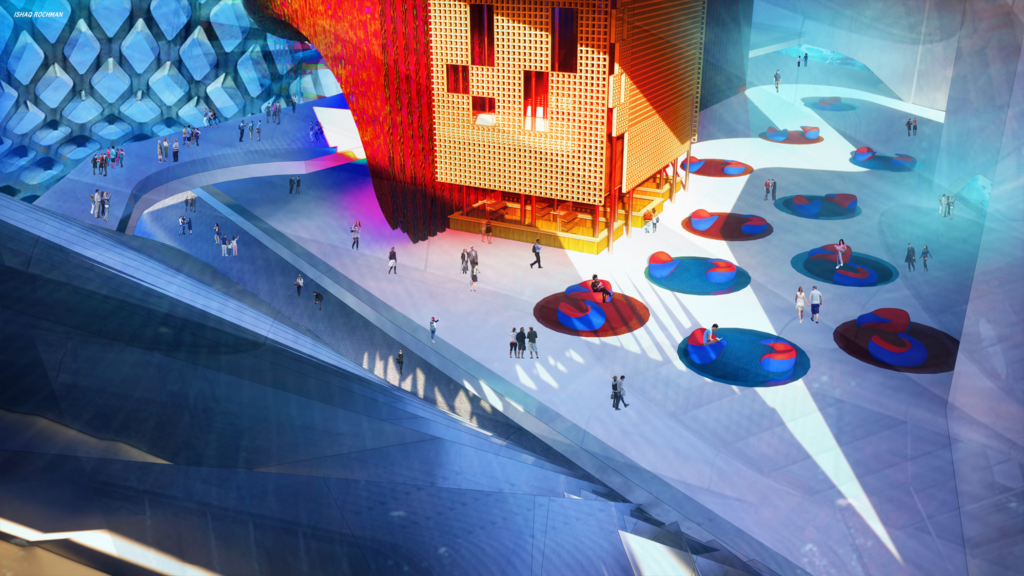

With your experience in projects that enhance the quality of urban life, what role do you believe public spaces play in fostering community interaction and well-being?

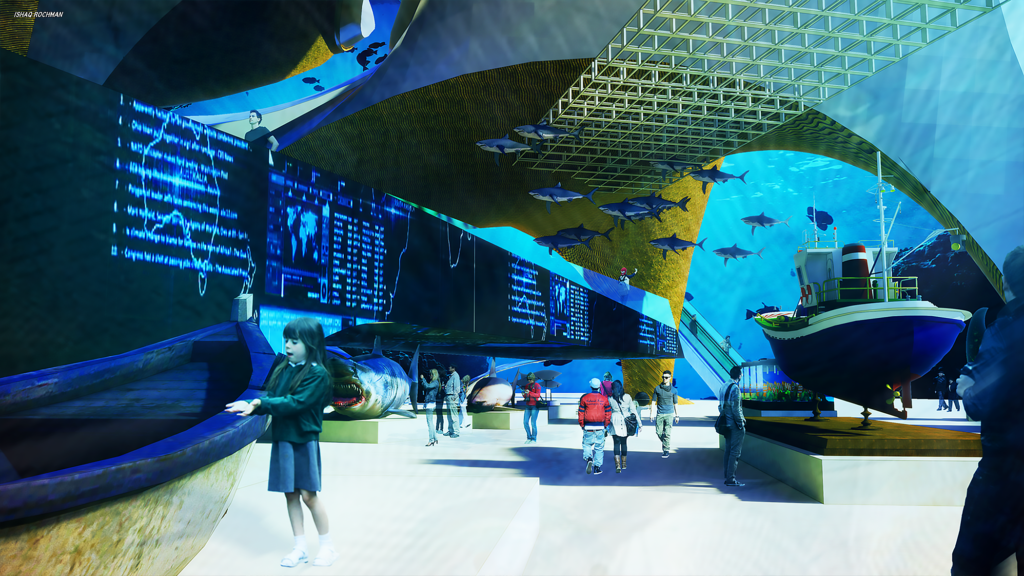

Ishaq Rochman: Public spaces are the heartbeat of urban life. They are not just gathering spots but places where social, cultural, and natural interactions converge, creating a collective identity and sense of belonging. In my projects, public spaces are designed as dynamic “living spaces” that encourage active citizen participation and enhance both physical and mental well-being.

1. Spaces for Social Interaction

Great public spaces break down socio-economic barriers. For example, in Cibus City, plazas with community gardens become places where farmers, artists, and families meet, share stories, and build connections. These are democratic spaces where everyone feels represented

2. Connection with Nature

Public spaces should bridge humans and nature. In Gap of Nusa, green corridors and floating parks not only beautify the city but also provide mini-ecosystems that purify air, reduce heat, and calm the mind. Such biophilic designs improve mental health by integrating natural elements into daily life

3. Adaptive, Multifunctional Spaces

Public spaces must be flexible, adapting to community needs. For instance, a town square can transform into a morning market, an art performance venue, or an environmental education space. In Cibus City, I designed modular stages that can be reassembled, allowing residents to organize events as they see fit

4. Spaces for Learning and Innovation

Public spaces can also serve as living laboratories. In Gap of Nusa, coastal areas are designed as educational spaces about marine ecosystems, where children can learn while playing. This fosters a generation that cares deeply about the environment

5. Well-being Through Inclusive Design

Public spaces must be accessible to everyone, including children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. In every project, I ensure safe pedestrian pathways, inclusive play areas, and comfortable seating for rest

Ultimately, great public spaces reflect the values of their communities. They are not just places but shared experiences that strengthen social bonds, improve quality of life, and create more humane cities.

©Gap Of NUSA by Ishaq Rochman

©Gap Of NUSA by Ishaq Rochman

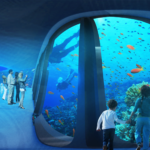

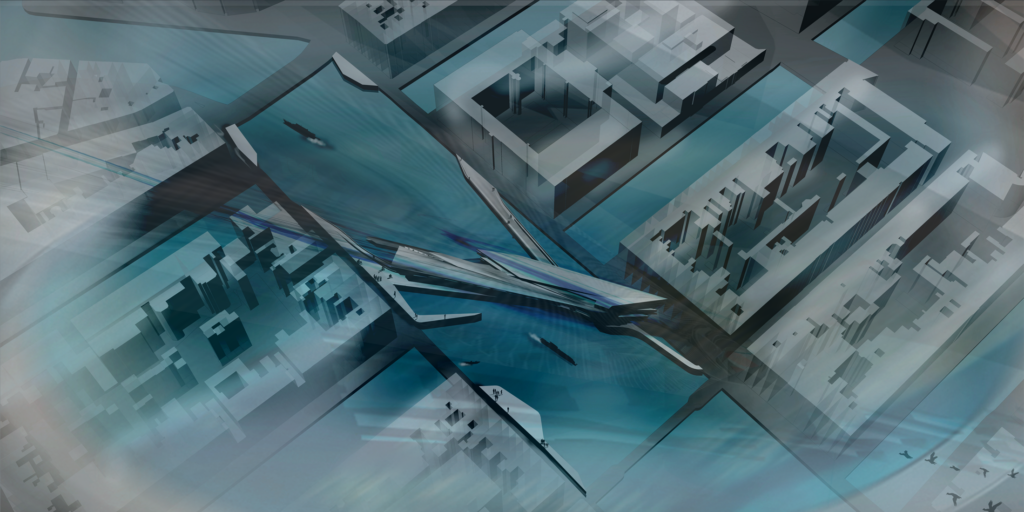

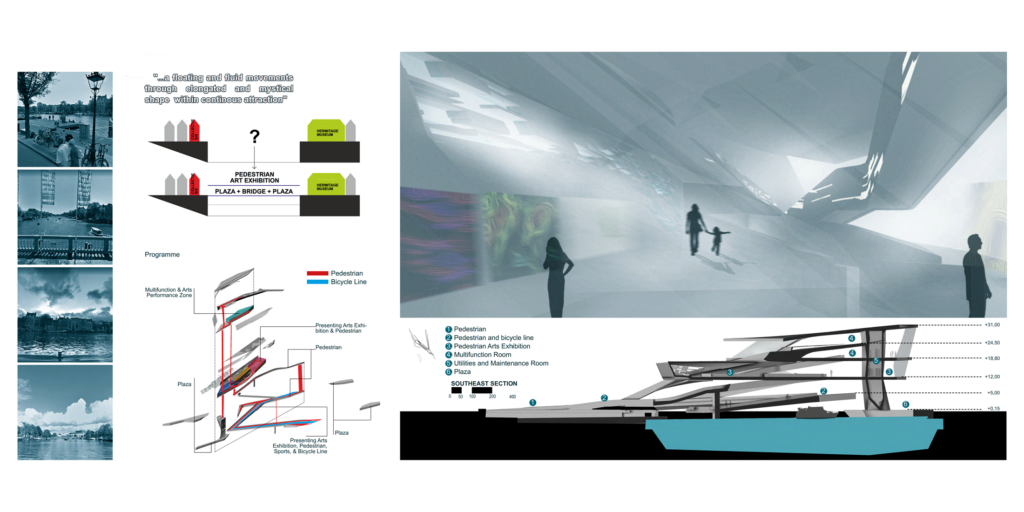

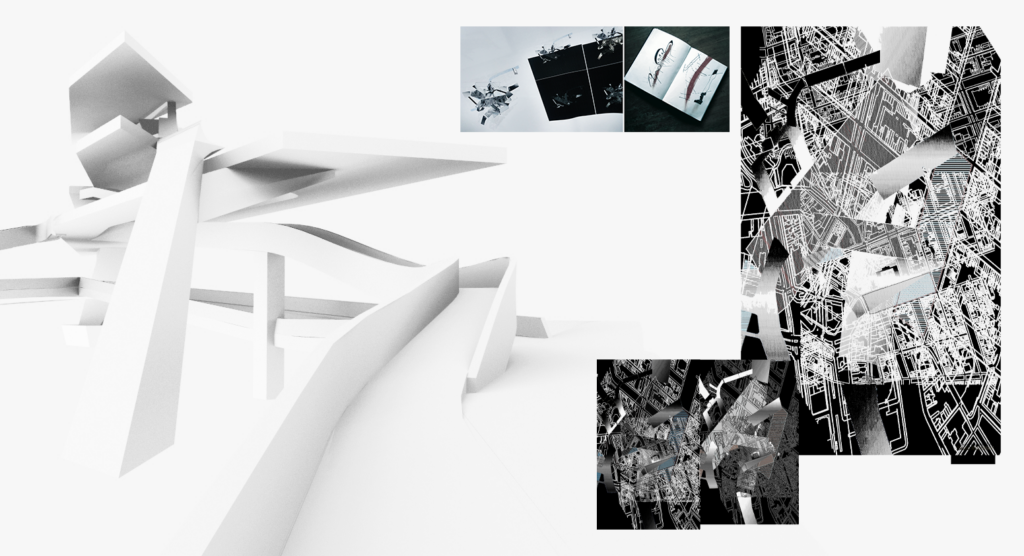

The design of the Connecting Line aims to create a mystical, floating line that enhances movement and connectivity while maintaining harmony with the surrounding cultural landmarks. Could you elaborate on the inspiration behind this elongated, flowing shape and how it complements the historical and cultural context of the Amstel River area?

Ishaq Rochman: The Connecting Line draws inspiration from the flow of water and cultural history along the Amstel River. Its elongated, flowing shape mirrors the movement of the river itself, which for centuries has been the lifeblood of Amsterdam—serving as a transport route, a source of life, and a symbol of the city’s identity.

1. Inspiration from Nature and Culture

The sinuous form of the Connecting Line is inspired by the way water moves: calm yet energetic, fluid yet connected. It also references Amsterdam’s iconic canals, which are not just infrastructure but living works of art. The design creates a dialogue between modernity and tradition, where the floating line appears to “dance” harmoniously with the surrounding historical buildings

2. Bridging Past and Future

The Connecting Line is designed to respect historical context without overshadowing it. For example, the use of transparent glass and lightweight steel allows the structure to “disappear” visually, ensuring cultural landmarks like old bridges and historic churches remain the focal point. At the same time, its futuristic shape introduces a contemporary touch, creating a contrast that enriches the area’s visual narrative

3. Enhancing Connectivity and Experience

This line doesn’t just connect point A to point B—it creates a pathway of experiences. By integrating seating areas, strategic viewpoints, and interactive art installations, the Connecting Line becomes a space where residents and visitors can pause, reflect, and connect with the river and its history. It’s a public space that invites interaction while celebrating the cultural identity of the Amstel

4. Harmony with the Environment

The design considers the river’s ecology. The floating structure is engineered to minimize disruption to water flow and aquatic habitats, while nighttime lighting uses low-energy LEDs that don’t disturb nocturnal wildlife

The Connecting Line is a tribute to the Amstel River—as a witness to history, a source of life, and an eternal inspiration. It’s not just infrastructure but a symbol of connectivity that ties together the past, present, and future.

©Connecting Line by Ishaq Rochman

©Connecting Line by Ishaq Rochman

©Connecting Line by Ishaq Rochman

©Connecting Line by Ishaq Rochman

In an ever-changing world where lifestyles, technologies, and cultural contexts continuously evolve, how do you ensure that your designs remain relevant and meaningful across generations?

Ishaq Rochman: In an ever-changing world, designs that remain relevant and meaningful must be flexible, adaptive, and rooted in timeless values. I ensure this through several approaches:

1. Responsive Design

I create spaces and structures that can evolve over time. For example, in Cibus City, residential modules and public spaces are designed to be repurposed as future needs change. Modular systems allow elements to be added or removed without compromising the design’s integrity.

2. Integrating Technology Wisely

Technology is a tool, not an end goal. I use updatable technologies like renewable energy systems and smart materials but ensure designs don’t rely entirely on tech that may become obsolete. For instance, in Gap of Nusa, IoT sensors monitor ecosystem health, but the physical infrastructure is designed to function even without them.

3. Respecting Cultural Context

Meaningful design celebrates local identity. I always involve communities in the design process, ensuring projects reflect local values and wisdom. For example, in the Connecting Line, the form inspired by the Amstel River and Amsterdam’s canals creates a sense of ownership for locals.

4. Prioritizing Ecological Sustainability

Climate change is a cross-generational challenge. My designs prioritize ecological resilience, using recycled materials, self-sufficient energy systems, and integrated green spaces. This ensures future generations can enjoy a healthy environment.

5. Creating Spaces for Interpretation

Great design “speaks” to each generation in its own way. I design spaces that allow for creative interpretation and adaptation. For instance, plazas in Cibus City can transform into morning markets, art spaces, or community gathering spots, depending on residents’ needs.

By combining flexibility, sustainability, and cultural respect, I aim to create designs that are not only relevant today but also meaningful legacies for future generations.