As part of our Design Dialogues series on Fublis, we are thrilled to present an in-depth conversation with Nithin Hosabettu, Design Director, IMK Architects. Established in 1957, IMK Architects is a trailblazing firm renowned for its commitment to sustainable, site-sensitive design. The firm has played a pivotal role in shaping India’s architectural landscape, marrying tradition with innovation to create spaces that prioritise harmony with nature and human well-being.

Through their legacy of groundbreaking projects—from pioneering terrace gardens in urban high-rises to integrating biophilic principles into institutional and residential designs—IMK Architects continues to lead the way in environmentally holistic architecture. Their work reflects a deep-seated philosophy of social and ecological responsibility, exemplified by projects such as the Symbiosis University Hospital and Research Centre and Balador Talegaon.

In this interview, we delve into IMK Architects’ design philosophy, their integration of modern technology with traditional principles, and their vision for architecture’s role in fostering wellness and sustainability. Offering a blend of thoughtful reflections and practical insights, this discussion is a source of inspiration for both seasoned architects and emerging talents striving to create meaningful, future-focused spaces.

Given the firm’s deep roots in sustainable and site-sensitive design, how has IMK’s approach to environmentally holistic architecture evolved over the decades, particularly with advancements in green technology?

Nithin Hosabettu: Since its inception, IMK Architects has focused on social consciousness and urban ecological sensitivity. The firm has designed green buildings since the 1960s, meaning a love for the natural environment is inherent to our practice and part of our architectural heritage. Our design and construction methods have always emphasised the careful selection and sourcing of materials.

For instance, at the Symbiosis University Hospital and Research Centre, Pune, we wanted to design a façade which required minimum maintenance. This influenced the choice of using the most abundantly available material in that region—earth. We used sundried Compressed Stabilised Earth Bricks made of a natural mix of different types of locally available soils, stabilised with 5% cement, ensuring their durability. They were made on-site using a block-making machine, cutting carbon emissions. The on-site manufacturing process also reduced transportation costs and material wastage. The bricks were sundried instead of kiln-fired, making it an environmentally friendly process. CSEB, through its porosity and its use in elements such as cavity walls and jaalis, enables the building to cope with the regional climate by allowing the building to breathe. This reduces the internal heat gain, allowing for maximum thermal comfort and reducing energy consumption.

The Sona University Centre integrates a vibrant, functional design while catering to student needs. How did you approach balancing aesthetic considerations with the functional requirements for students and faculty in this space?

Nithin Hosabettu: The design of the Sona University Centre and Library Block prioritises user-centricity while focusing on the spatial harmony of the campus and efficiency. The Block’s striking stepped facade and modern materials create a visually dynamic identity that complements the campus’ architectural language. The design incorporates multiple interactive areas, such as an indoor plaza, amphitheatre, and café, to encourage collaboration. The Block also incorporates natural ventilation, daylight integration, and heat-reducing louvres ensure a comfortable and bright indoor environment. The design choice to build the granite steps leading up to the Block around the existing trees enhances the campus experience by adding character to it while respecting the site’s natural context.

©Sona College of Technology,Salem by IMK Architects

©Sona College of Technology,Salem by IMK Architects

©Sona College of Technology,Salem by IMK Architects

©Sona College of Technology,Salem by IMK Architects

This center showcases modern architectural themes while respecting the educational context. What were some challenges in integrating a forward-looking design within the existing campus aesthetics, and how were these overcome?

Nithin Hosabettu: The design process of the Sona University Centre and Library Block presented several challenges, including maintaining visual harmony with the historic Heritage Block, preserving the campus’ cohesive identity, and addressing the scale and prominence of the new structure. As a result, the design carefully modulated the size and placement of the Admin and Library Block. The stepped facade ensured that the new building did not dominate the vista while establishing its status as a landmark.

The design also prioritised the site’s natural environment and worked around existing trees. They were incorporated into the layout, with the granite steps serving as an outdoor plaza connecting the building to the rest of the campus, seamlessly blending the natural and built environments.

The university block was designed to sit next to the main block, which had well-balanced proportions. The goal was to create a structure that would complement, rather than dominate, the main block, making it an integral part of the main plaza. The proportions were carefully worked out to enhance the space. We retained the essence of the entire plaza by reusing the existing brick paving and maintaining the same texture and alignment. This approach ensured that the new block harmonised with the plaza while preserving the original character and legacy of the main block. This way, we revitalised the plaza while staying true to its original spirit.

With a long-standing legacy of innovative projects, how does IMK Architects maintain a balance between honoring its architectural heritage and embracing modern techniques and technologies in its designs?

Nithin Hosabettu: Architecture is about envisioning what can be created anew for the user—how a space can improve upon what came before. It’s about progress: refining the design to enhance the user’s experience, making the space more comfortable, functional, and aesthetically pleasing. Over time, we have advanced in our design approach, focusing on improving how people feel in the spaces we create and how they interact with them.

We progress from embracing new technologies, construction methods, and materials always striving to create something better. Every project is an opportunity to push boundaries—integrating innovation, sustainability, and social responsibility. We are committed to learning from our past mistakes and using those lessons to improve our future work. Architecture is about helping the user thrive, refining the balance between form, function, and environment. It’s about challenging ourselves to create spaces that are not only user-friendly but also forward-thinking, responsible, and sustainable.

Could you share how specific architectural choices in Symbiosis University Hospital and Research Center were guided by the goal of enhancing patient comfort and well-being?

Nithin Hosabettu: The design of Symbiosis University Hospital and Research Center (SUHRC) was guided by a deep commitment to enhancing patient comfort and well-being. Biophilia is a key design consideration, with terrace gardens, courtyards, and landscaped areas offering patients and their families calming natural landscaped spaces, which foster healing and reduce stress.

The hospital’s internal spaces are designed to emphasise daylight and natural ventilation. We used courtyards and skylights to ensure that the interiors receive sufficient daylight and that areas like the Out-Patient Department (OPD) and waiting zones are naturally ventilated, reducing the need for artificial air conditioning. This approach creates a more human-centric atmosphere. Intuitive layouts, wayfinding, and clear markers like colour-coded nurse stations reduce the anxiety of navigating the building.

For inpatients, the design of SUHRC prioritises privacy and comfort. Wardrooms feature soothing colours, the natural feel of wooden palettes, and views of the landscaped surroundings. Critical areas such as ICUs and operation theatres are strategically located to ensure sterility and separation from high-traffic zones, while wide corridors adjacent to courtyards enhance accessibility. Acoustic materials reduce noise pollution, contribute to a serene environment, and custom-designed furniture caters to diverse patient needs.

©Symbiosis University Hospital and Research Center, pune by IMK Architects

©Symbiosis University Hospital and Research Center, pune by IMK Architects

©Symbiosis University Hospital and Research Center, pune by IMK Architects

©Symbiosis University Hospital and Research Center, pune by IMK Architects

©Symbiosis University Hospital and Research Center, pune by IMK Architects

©Symbiosis University Hospital and Research Center, pune by IMK Architects

©Symbiosis University Hospital and Research Center, pune by IMK Architects

Given that the hospital is part of an educational institution, were there unique challenges in blending a professional medical facility with the campus setting, and how did you approach these?

Nithin Hosabettu: Blending a professional medical facility with an educational campus did present unique challenges. One was designing for diverse user groups, including medical professionals, patients, students, and researchers. The hospital’s layout incorporates zones that cater to these varied needs, with clearly defined spaces for treatment, education, and research. For example, classrooms and seminar halls are strategically located away from patient care areas to avoid disruptions while facilitating ease of access for medical students and faculty.

For young architects interested in multidisciplinary practice, what key insights from IMK’s decades of expertise would you suggest they consider as they develop their own approach to socially and environmentally responsive architecture?

Nithin Hosabettu: The construction industry is responsible for approximately 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions, making its impact on climate change significant. As architects, it becomes our responsibility to design buildings that are both socially and environmentally responsible—architecture that is sustainable. Every aspect of our approach should reflect this commitment, so much so that it becomes second nature, an involuntary reflex.

Our design process must always consider sustainability as the baseline. This means not only addressing the specific needs of our clients but also going beyond those needs to create structures that are in harmony with nature. The buildings we design should meet current demands and ensure that they do not harm the environment in the future. We should prioritise reusable materials, reduce carbon footprints, and embrace sustainable practices as the standard approach. A responsible design approach should no longer be seen as an exception but as the norm—a necessary step toward a more sustainable and harmonious future.

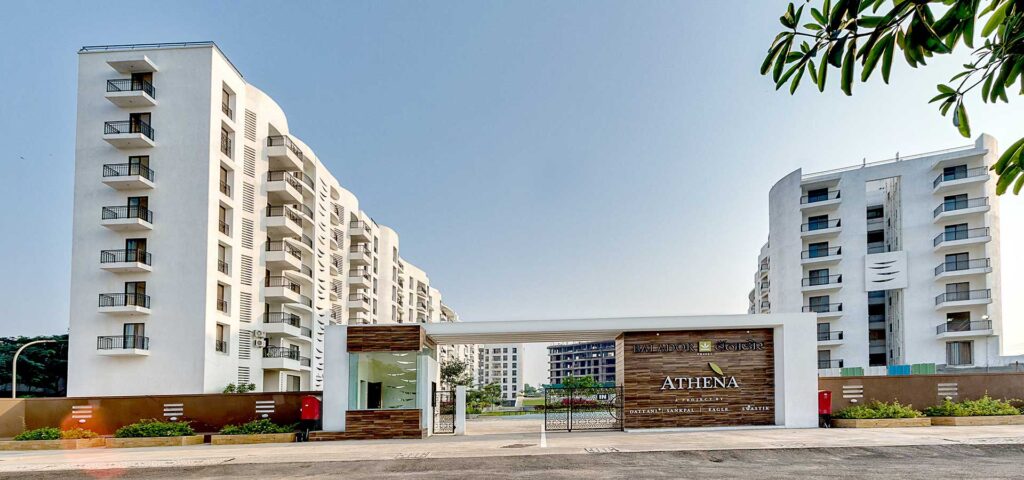

The project Baledor Talegoan’s vision emphasizes harmony with its natural surroundings. Could you elaborate on how specific design elements were incorporated to blend with the local landscape and enhance residents’ connection to nature?

Nithin Hosabettu: The design of Balador Talegaon seamlessly integrates with its natural surroundings by incorporating elements that echo the local landscape. The central courtyard, inspired by the contours of the Sahyadri mountain range, features cascading water elements and tiered green spaces that mirror the natural terrain. Buildings are oriented to maximise views of the Talegaon lake and mountains, while large balconies, green rooftops, and open facades create a strong indoor-outdoor connection. Vehicular routes are relegated to the periphery, ensuring a pedestrian-friendly central zone that enhances residents’ interaction with nature. The façade of the project was designed with the concept of blending the wings into one continuous form. The entire curvilinear façade features three distinct curves at different levels, seamlessly merging, creating a sense of unity. The wings do not have separate identities; instead, they combine to form a cohesive whole. This design enhances the feeling of a single, unified community within the project.

©baledor talegoan,Pune by IMK Architects

©baledor talegoan,Pune by IMK Architects

©baledor talegoan,Pune by IMK Architects

©baledor talegoan,Pune by IMK Architects

©baledor talegoan,Pune by IMK Architects

Considering the community’s goal to promote wellness, what architectural strategies did you implement to promote a sense of calm and rejuvenation within the space?

Nithin Hosabettu: To foster wellness, Balador Talegaon incorporates design strategies that promote relaxation and social interaction. The central courtyard, with its amphitheatre, water cascades, and green courts, provides a serene community space. The pedestrian-friendly layout also ensures a safe and peaceful environment. The buildings’ hierarchy of spaces ensures privacy within homes, while the dining and living areas are oriented to maximise natural light and ventilation, fostering a sense of openness. The smooth, curvilinear façade and interplay of textures evoke a feeling of warmth and comfort, further enhancing the overall sense of well-being.

Given IMK’s dedication to biophilic architecture, how do you envision this approach shaping the future of architecture? Do you think it is crucial for addressing urban challenges, well-being, and sustainability in the built environment?

Nithin Hosabettu: Biophilic architecture is a defining feature of IMK, with the firm setting a benchmark for integrating nature into design. IM Kadri pioneered the concept of terrace gardens in Mumbai, bringing nature into the heart of urban spaces. Landmark projects such as the Nehru Centre, Shivsagar Estate, and numerous five-star hotels have embraced this vision. Each project blends seamlessly with nature rather than standing apart from it. In addition to their aesthetic and environmental benefits, IMK’s projects focus on using natural, sustainable materials, reducing energy consumption, and minimising client costs. The future of architecture lies in this efficient, sustainable approach that reduces the construction industry’s environmental impact.

Architecture’s role in mitigating climate change is vital. By collaborating with other stakeholders and raising awareness, we can create a built environment that meets today’s needs and ensures a sustainable future that future generations will be grateful for. The approach to design, rooted in sustainability, should be the foundation of every project moving forward.