Welcome to Design Dialogues, an interview series by Fublis dedicated to showcasing the innovative minds and creative journeys of architects and designers who are making a significant impact in the industry. Through in-depth conversations, we celebrate achievements, explore unique perspectives, and share insights that inspire both peers and emerging talent.

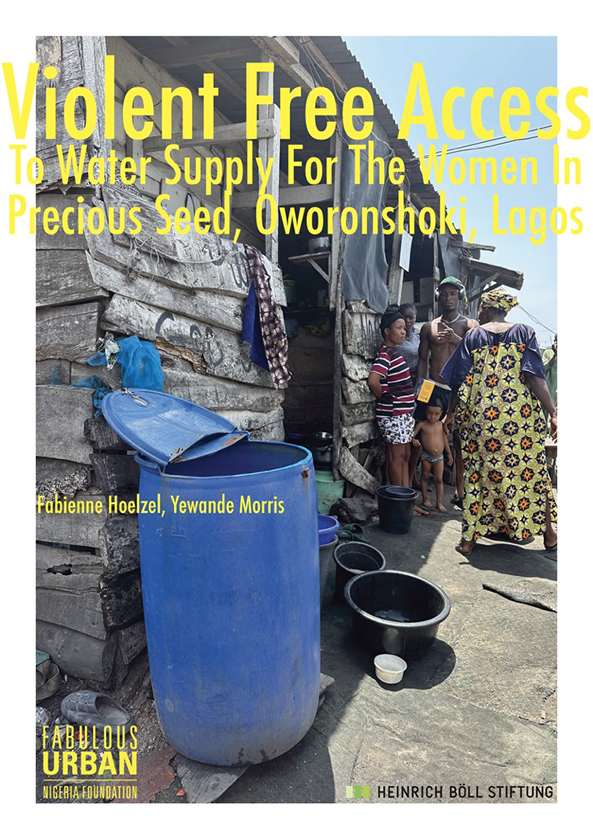

In this edition, we are proud to feature Fabulous Urban, a research-led and community-focused urban design practice with a remarkable presence in the Global South. Founded in Switzerland in 2014 and further established as Fabulous Urban Nigeria Foundation in 2021, the studio is committed to tackling critical urban challenges in some of the world’s most marginalized communities.

Under the leadership of Fabienne Hoelzel, the practice takes a feminist and community-centered approach to urban design, addressing issues such as water accessibility, housing affordability, and women’s empowerment. Fabulous Urban’s projects blend immediate, impactful solutions with long-term, systemic strategies, positioning them as a pioneering force in inclusive urban design.

In this conversation, we explore how Fabulous Urban embeds itself into local practices, collaborates with strategic actor-networks, and leverages urban planning as a tool for social equity. From modular housing solutions to circular sanitation systems like MDDT, Fabienne Hoelzel and her team demonstrate how thoughtful, context-sensitive design can transform lives and communities.

Join us as we delve into their challenges, achievements, and unwavering commitment to creating equitable urban systems that serve those who need it most.

Your studio Fabulous Urban emphasizes a research-led and community-based approach to urban design. Could you elaborate on how embedding into local practices and strategic actor-networks has shaped your projects and outcomes in the Global South?

Fabienne Hoelzel: Fabulous Urban is registered in Switzerland since 2014, and in Nigeria as Fabulous Urban Nigeria Foundation since 2021. We work with and in poor “slum” communities. There are two types of projects: One is to respond to the needs of – mostly – women with immediate effect. An example of such a project is MDDT. Two is to act as think-tank with either providing research on issues such as female everyday practices or providing position statement that can be fed into the political process. Hence, local practices are the starting point and the target of all our projects. However, we use whatever knowledge and/or technology that is useful to provide approaches and knowledge to improve the lives of poor people, and especially poor women.

The report highlights the intersection of social, economic, and infrastructural issues in Precious Seeds. How do you approach designing urban systems that address the immediate need for reliable water access while also tackling the broader social and economic inequities faced by women in such communities?

Fabienne Hoelzel: This dilemma will probably never go away, as we work in certain systems (of belief), which are hard to change, i.e. the subordinate position of women (a mix of culture, politics, religion etc.) or that only large-scale infrastructure is real politics. The approach is hence two-fold: Implement situational, selective projects and approaches, that serve for ourselves as research and for the public as examples, how several systems could coexist, i.e. large-scale network solutions and small-scale, relational off-grid solutions. Like that, hopefully, the systems (of belief) could be changed. In the end, it’s about power and access to the decision of power.

©Fabulous Urban

Given the cultural environment where women are solely responsible for household chores, how can urban design and planning empower women socially and economically while addressing the critical issues of water accessibility?

Fabienne Hoelzel: This is a dilemma as well. By proving projects for the women that ease their lives, e.g., better/faster/safer access to (clean) water, we’re in a way reinforcing the gender roles that, e.g., foresee that women are responsible to fetch the water. On the other hand, improving the access to water for the women, makes room and time in their lives, which they can invest in running their businesses. This again enables them to have (one day) a self-determined life. However, one should not overestimate the influential power urban design and planning may have, but we should also not underestimate the power it can have, especially when done from a feminist perspective.

Your focus on feminist urban planning and infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa is unique. What challenges have you faced in advancing these principles in your projects, and how do you address cultural and systemic barriers?

Fabienne Hoelzel: The biggest challenge is certainly that feminist urban design and planning is considered to be something for women only, hence it’s considered to be an add-one and inferior (it’s only for the women). Unfortunately, “feminist” is perceived as “combat term”, as “something against men”. A way out is to use terms like gender-responsive or inclusive urban design. However, as a feminist I think we should name things by name. Women represent half of humanity, yet they are in almost every country discriminated – culturally, politically, not to speak of religion. If we do not name that, and if do not implement feminist urban research and feminist urban design, things will change. In the end, again, it’s about power, access to power, and access to decision making processes. So, I/we keep going, get used to criticism and rejection, sometimes get a rest, and then keep on improving communication in the sense of: explaining things better. It’s a bumpy road but the only way to go. Social rights were never given, they have to be fought for.

©Fabulous Urban

©Fabulous Urban

©Fabulous Urban

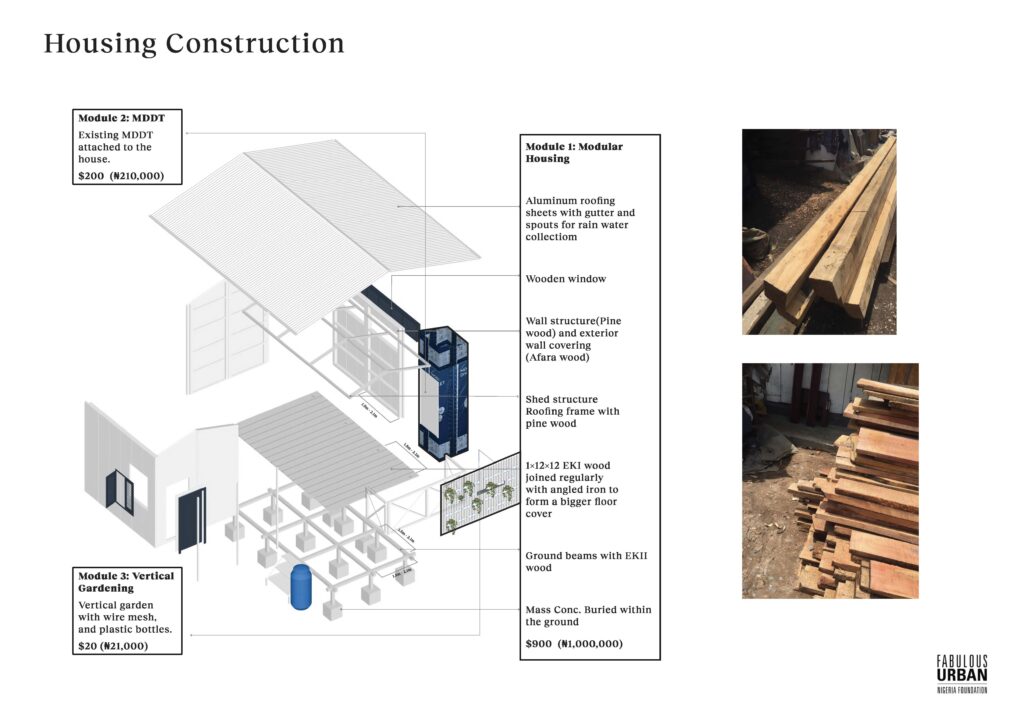

The reconstruction scheme of Precious Seeds focuses on simple, modular, and affordable housing. How did you approach designing a system that balances functionality, cost-efficiency, and adaptability for a community with such significant socio-economic constraints?

Fabienne Hoelzel: When working for the extremely poor who live on one or two dollars a day, the entire thinking and approach has to come from the economic angle. This is not a choice, it’s simply a given. However, despite of attempting to design a house for roughly 1000US$, the women can’t afford it. The combination of a strong(er) US$ and of permanently low(er) local currency that has lost permanently value over the last years, lead to ever soaring material prices (wood, metal, etc.). Even when the cost price of the house is pre-financed, without interest rates of course, the women could pay back in four years or so. This does not make a lot of sense in an environment where forced evictions are a permanent threat and the women live from hand to mouth. To cut it short: we have not succeeded to come up with housing design that is affordable enough and/or we have not found the (pre(funding models that would enable it. For a number of reasons, we do not want to work with purely donation-oriented models. It’s not sustainable and not “systemic” enough. But we have also not given up, but we will have to invest more brain and time. Depending on our own funding, we plan to do that in the course of 2025 or 2026.

Incremental development is a critical aspect of the scheme, given funding and logistical challenges. How do you plan to maintain design consistency and community cohesion as the project progresses over time?

Fabienne Hoelzel: I’m not sure whether “incremental” is the right term. As mentioned, I believe it’s about a two-fold approach. One aspect is about immediate support and/or improving the lives of maybe even “only” a handful women. The second aspect is about showcasing trough the latter and additional research/position statements etc. offering an additional system, changing parts of the system, or potentially an entire system (by introducing a mortgage system for extremely poor women, a new law, etc.). We have not yet found that key, maybe we never will. But we’re trying hard to be able to offer such an affordable, fundable house that might ideally then become more systemic, both in terms of implementing a “master plan” or creating housing solutions for extremely poor women in general.

©Fabulous Urban

©Fabulous Urban

Fabulous Urban operates across multiple scales, from strategic planning to detailed construction design. How do you maintain a cohesive design vision while addressing the diverse and complex needs of the communities you serve?

Fabienne Hoelzel: I would give a similar answer as above. The cohesive (design) vision has the two aspects of the immediate emergency relief aspect and of the longterm systemic change or adaption. This is well visible in the MDDT project. It provides now a few dozen women-led households with private toilets but of course, the goal is that it becomes large scale, which really would make a difference concerning safety, health, and (personal) hygiene for neighborhoods and cities. It was also enable more economic approaches, hence a systemic waste disposal that might create jobs. Right now it’s still quite situative and selective. It’s not about the classic scaling up but about designing strategic projects that can be both, small and big, but not in terms of sheer size and mass, but efficiency in providing lasting solutions for the most urgent, simplest and yet unsolved issues.

The use of waste as a resource, either for income generation or home gardening, is a unique aspect of the MDDT project. How do you support and educate the beneficiaries to maximize the economic and environmental benefits of this circular system?

Fabienne Hoelzel: In Lagos. the women and their households are pragmatic and hands-on. The waste disposal was never an issue. We maintain a closely timed monitoring system, once a week, but the households do empty and exchange the waste sacks and urine cans themselves. The next step here really is to have as many MDDTs in a neighborhood that we have a professional waste collection. In Nairobi, where we plan to start with MDDT as well, it’s quite the opposite. The waste disposal is a big issue, there is more fear and skepticism around the waste disposal. We’re still working on it but still hope to be able to start a round of pilot MDDTs in the first quarter of 2025. The women were already selected.

©Fabulous Urban

The MDDT has been carefully designed with women’s safety and dignity in mind. What were the key insights from the field tests and user feedback that shaped the final design, and how did these insights influence your approach to addressing the needs of low-income communities?

Fabienne Hoelzel: It was quite a bumpy road and still is. The cost price is right at 250 US$, which is still too high. The goal is 50 US$ or so … I’m very happy that we’ve now implemented the first series with a “counter-funding” model. The toilet is given to the women, funded by one of our donors, a Swiss foundation. Half of the cost-price they will back though, in the course of 12 months with tiny monthly repayment rates. We’re now also exploring other models like rent or lease systems. Having said that, we’re struggling with the costs. Nevertheless, there are plans to add solar-powered light, for even more security.

The idea was from the beginning to think in modules. We were planning to sell only the “engine” (squat pan, tubes, barrels, and can) and the “shell” (frame and tarpaulin), with the idea in mind that the “shell” is optional and could theoretically be built by the women as they wish and as resources can be mobilized (funds, materials). In practice, everybody wants engine and shell … the form and functional elements were developed in a very experimental way. We first produced a prototype that was discussed and modified, then we produced two refined prototypes that were used during 6 months, closely monitored. One of these prototypes is still in use. The changes applied were mostly concerning materials, hence the durability and the resulting aesthetics. We improve with every round of new implementations, which is usually ten MDDTs at once. It’s still small-small and very carefully done as we are looking for a 100% success quote. One MDDT failed as the husband wouldn’t allow his wife to use the toilet. We talked to him, gave him time to reflect and his insisted of not letting her using it, we had to take it away from him. From that day one, we have only been working with the women directly. This was a hard learning: whenever both, husband and wife, man and women, are addressed and included into the project at once, the husband/man would take over and the wife/woman is automatically subordinate. This of course confirms the necessity of explicitly feminist urban design approaches.

Your work reflects a deep commitment to addressing critical urban challenges. What inspired you to pursue this path, and what continues to drive your passion for creating equitable urban solutions? What advice would you offer to fellow urban designers aiming to make a meaningful impact in similar contexts?

Fabienne Hoelzel: I believe I was always interested in engaging in pressing challenges. In 2010 I moved to São Paulo (Brazil), where I worked three years at the city’s housing and urban development department responsible for the local slum-upgrading program, funded by tax money and international funds. After that experience of three years in total, I decided to found my own organization, applying a more research-led and strategic approach. As I have had almost always one leg up in academia and research, I do not have to rely on the organization to pay my rent. Since 2017 I have been a full professor of urban design, providing the freedom we need to run the organization with a small-small approach, slowly developing, implementing, and testing approaches without the pressure to “scale up” and become “big”. I’m not sure whether I have an advice but I would like to invite everybody to contribute to the most pressing yet unsolved issues like safely managed toilets for everybody and especially women and girls, access to safely managed water, and decent housing for all, especially the women – hence proving privacy and space that can be safely locked. Domestic violence, including sexual violence is one of the most prevailing issues extremely poor women and girls from age 10 on have to deal with.