At Fublis, our “Design Dialogues” series is dedicated to exploring the minds of architects and designers who are redefining the built environment through innovation, cultural sensitivity, and fresh perspectives. Through in-depth conversations, we celebrate their achievements and uncover the philosophies that shape their work, offering valuable insights for both industry professionals and emerging talent.

In this edition, we feature ELSE Design, a practice known for its unconventional approach to architecture. ELSE challenges conventional boundaries by finding opportunities for transformation within everyday spaces. Their work is not about creating iconic landmarks but about reshaping perspectives on how design integrates into daily life, fostering meaningful engagement with the built world.

In this interview, ELSE Design delves into the philosophy behind their projects, from the Beiqing Experimental School Boundary Renovation, which reinterprets traditional Chinese architecture in a contemporary context, to the Periscope Hut, a structure designed to enhance the experience of nature. They also discuss the complexities of working across diverse cultural and regulatory landscapes, the balance between cultural heritage and modernity, and their unique global outlook shaped by experiences in China, Europe, and the United States.

Join us as we explore ELSE Design’s thought-provoking approach to architecture—one that embraces alternative perspectives and challenges the status quo.

ELSE Design emphasizes innovation and boundary-breaking in everyday reality. Could you elaborate on how this philosophy influences your approach to integrating design into daily life?

Zhifei Xu: I’m bored of uninspired architecture. I don’t like design that feels lazy in its thinking—doing something mundane just for the sake of making a living is not why we stay in this profession. We want to design something else.

Daily life is full of design potential. It’s not just about constraints or routines we blindly accept. And it doesn’t have to be about big, flashy projects—landmarks by star architects or radical statements. Even in the most ordinary briefs, functional requirements, or seemingly unremarkable sites, there’s always room for a twist, a shift in perspective that brings something unexpected.

This is what makes architecture meaningful. For us, the best thing architecture can offer is an alternative perspective on the world—one that encourages new ways of thinking and engaging with our lives.

Beiqing Experimental School Boundary Renovation project redefines the school’s boundary by integrating traditional Chinese architectural elements with an innovative folding design. How did you balance the preservation of cultural identity with the need for contemporary functionality?

Zhifei Xu: Being an architect in a country with such a long architectural history comes with a certain historical weight. China has a rich architectural tradition, but unlike many Western countries that naturally evolved their own modernist movements, we encountered a sudden and intense external influence before fully transitioning into a modern architectural era of our own. For me, rethinking and reinterpreting Chinese architecture is not just a creative pursuit—it’s a responsibility, a challenge, and an opportunity.

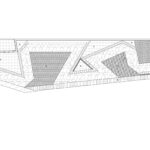

That said, the Beiqing Experimental School Boundary Renovation is a relatively small- scale project, driven more by practical needs than aesthetics. The boundary needed to manage pedestrian and vehicular flow, prevent traffic congestion, and provide a comfortable waiting area for parents. In most cases, the visual and cultural aspects ofschool gate design are secondary—many Chinese schools prioritize strict functionalism over architectural expression. I grew up in such schools myself, where the entrance was often just a gap in a wall or an exaggerated, imposing structure.

However, when looking at Chinese universities, especially those built earlier, many still carry the essence of traditional architecture. Their entrance gates serve as markers of identity and continuity with the past. This project became an opportunity to bridge that gap—drawing from the cultural significance of traditional gateways while adapting to the needs of a contemporary school environment.

The folding design in this project unifies three distinct functional elements of the new boundary: the gate, the guardroom, and the parent waiting area. At the same time, it distills the fundamental spatial and formal composition of traditional Chinese architecture, allowing its spirit to be felt even in a contemporary form.

©Beiqing experimental school boundary renovation hut by ELSE

©Beiqing experimental school boundary renovation hut by ELSE

The decision to push the boundary inward by 10 meters created a new triangular plaza, reshaping both the entrance experience and public engagement. How did this spatial intervention evolve from an architectural and urban planning perspective?

Zhifei Xu: The decision to push the boundary inward by 10 meters was both a practical response to urban conditions and an opportunity to improve the entrance experience. Since this project involved turning the original back gate into the new main entrance, the site presented a significant challenge—the back gate was located on a narrow secondary road, with limited pedestrian space that couldn’t handle the surge of students and parents during peak hours. Without intervention, congestion and conflicts between pedestrians and vehicles would have been unavoidable.

By setting the boundary back, we created a buffer zone that helps ease pressure on the sidewalk and improve overall safety. The new triangular plaza absorbs waiting crowds,

allowing for a smoother and more organized flow of people. At the same time, this shift transformed the entrance from a simple gate in a wall into a spatial transition, making the school feel more open and engaged with its surroundings. More than just a functional adjustment, this intervention creates an urban gesture, subtly redefining the relationship between the school and the city through a carefully considered spatial move.

©Beiqing experimental school boundary renovation hut by ELSE

©Beiqing experimental school boundary renovation hut by ELSE

The transformation of an institutional boundary into a welcoming public space is a rare architectural approach. Were there any unexpected challenges—whether cultural, regulatory, or technical—that reshaped your design thinking during the project?

Zhifei Xu: In the process of bringing this project to reality, we encountered several challenges. The school administration naturally had concerns about boundary management, and coordinating with municipal authorities on the interface between the school and the public space was more complex than anticipated.

Ultimately, the final built project did not fully achieve the ideal outcome, but that is the nature of architecture. Interestingly, after completion, a municipal agency in Guangzhou included it in their best practice case studies, which perhaps signals a broader recognition of this approach. In some ways, the project serves as an example of an alternative way to think about institutional boundaries, opening up possibilities for future explorations.

©Beiqing experimental school boundary renovation hut by ELSE

©Beiqing experimental school boundary renovation hut by ELSE

With projects spanning the United States, Europe, and China, how does ELSE Design navigate the diverse cultural and regulatory landscapes to maintain a cohesive design ethos?

Zhifei Xu: At ELSE, our way of seeing comes from the way we have lived. Though we are both Chinese, one of us spent ten years in the U.S., the other ten years in Europe. A part of us has always been here, yet much of our lives has been shaped elsewhere.

Abroad, we were familiar outsiders—deeply engaged, yet always aware of the lines that defined us as foreign. Back in China, that feeling doesn’t disappear. We see things a little differently from those who have always been here, not distant, but slightly apart. It’s a perspective that lingers between worlds, close enough to understand, distant enough to observe. Our practice name ELSE reflects this in its own way—almost like being “somebody else.”

This experience has made us sensitive to different places and cultures, attuned to the contrasts and connections between them. That’s why our projects often carry two distinct qualities: on one hand, they feel contemporary, standing apart from their surroundings; on the other, they are deeply rooted in local culture, subtly resonating with things buried in collective memory. It’s about finding that space where something new can feel unexpectedly familiar.

The Periscope Hut reinterprets the relationship between people and nature by framing the waterfall in a unique way. How did the idea of using a periscope element emerge, and what were the key design challenges in integrating this feature into the hut?

Zhifei Xu: The idea for the Periscope Hut comes directly from the site. In the distance, there’s a waterfall—subtle, almost just a thin line in the landscape. We didn’t want visitors to walk past without noticing it. Instead, we hoped the hut could draw attention to it in a quiet but intentional way.

That’s how the periscope element emerged. Rather than just offering a clear view, it creates a small moment of discovery—a way to pause and see differently. It frames the waterfall so that it doesn’t just blend into the background but becomes something to notice and experience. The hut, in this sense, isn’t just a shelter; it’s a tool for seeing.

The challenges came mostly during the construction. The periscope relies on an arrangement of mirrors to redirect the view. Achieving the right angles and ensuring a clear reflection required meticulous testing and adjustments.

©Periscope hut by ELSE

©Periscope hut by ELSE

Given the remote nature of the site, what specific environmental and climatic factors did you have to consider in the construction and material selection to ensure durability and minimal ecological impact?

Zhifei Xu: The approach to construction and material selection for this project was largely shaped by the competition brief, which set clear yet thought-provoking constraints. The organizers required the use of locally sourced spruce wood, harvested directly from the site. Unlike standardized timber—such as the industrial 2x4s commonly used in the U.S.—these logs were unprocessed and varied in size. This meant that the design had to account for a degree of uncertainty in construction, favoring a relatively simple and adaptable building method.

What’s particularly interesting is that, under the competition’s framework, structures like this are not meant to be permanent. Once the pavilion reaches the end of its use, villagers will dismantle it and repurpose the wood as firewood for winter. In a way, the project seamlessly integrates into the local material cycle, reinforcing its connection to the place—not just through its construction, but through its eventual return to the landscape.

©Periscope hut by ELSE

©Periscope hut by ELSE

Given your international experience with renowned firms, how have these diverse influences shaped the design principles and practices at ELSE Design?

Zhifei Xu: One of the most valuable lessons from working at renowned international firms was understanding how they operate, the standards they set, and the effort required to achieve

them. At the same time, because our experiences have been so diverse, we’ve also made a conscious effort to ensure that our work has its own identity, rather than being a reflection or imitation of the well-known firms we’ve been part of.

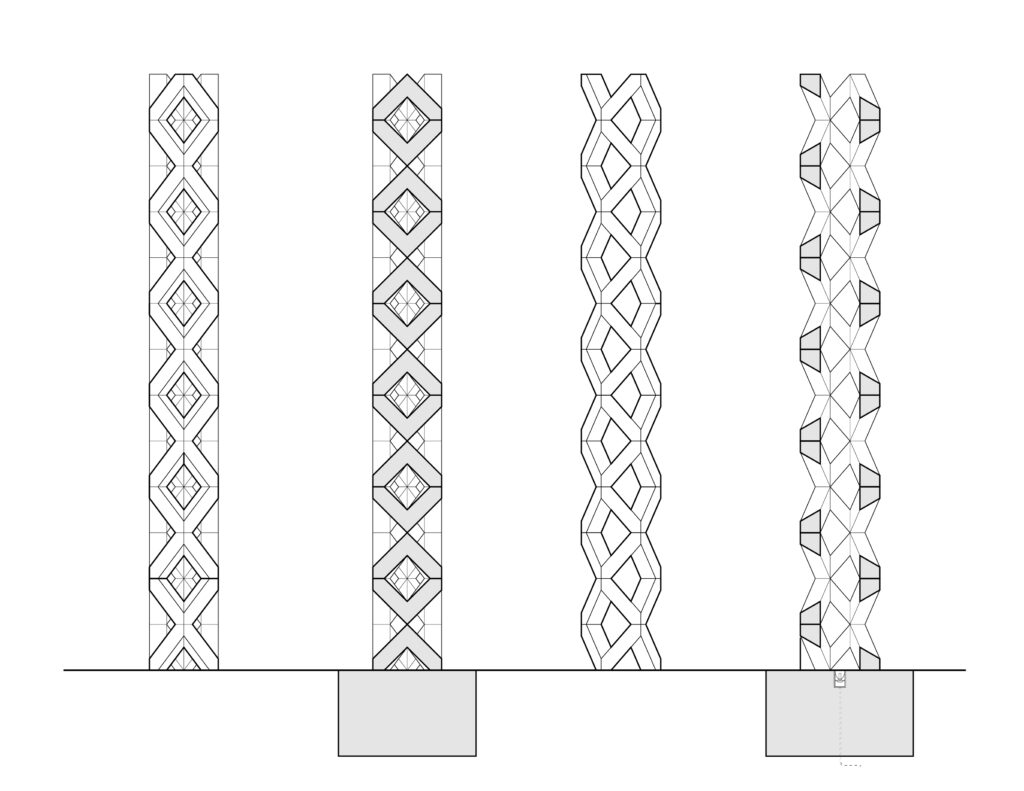

Architecture often serves as a bridge between history and modernity. When designing Shenchong Totem, how did you approach the delicate balance between preserving cultural memory and making a bold, contemporary statement with the entrance sequence?

Zhifei Xu: For Shenchong Totem, balancing cultural memory with a bold contemporary statement began with studying the village’s unique masonry technique. Shenchong is known for its black volcanic rock laid in a diamond pattern, a method that defines its architecture and reflects the villagers' deep connection to nature.

Inspired by this tradition, we extracted and simplified its geometric essence, creating a distinct motif that reinterprets local craftsmanship while symbolizing the village’s identity. The form subtly recalls regional plant life, such as sugar apples and palm trees, reinforcing its connection to place. This motif was translated into a series of modular black volcanic rock pillars, rhythmically placed along the entrance road to introduce order and spatial progression, guiding visitors into the village. Their verticality and abstraction evoke a totemic presence, creating a sense of monumentality and mystery, while remaining deeply rooted in local memory.

©Shenchong Totem by ELSE

©Shenchong Totem by ELSE

©Shenchong Totem by ELSE

ELSE has received multiple awards and media coverage shortly after its establishment. To what do you attribute this rapid recognition in the architectural community?

Zhifei Xu: We’ve been fortunate to receive recognition so early on, but it also reflects a broader shift in the architectural community. There is a growing interest in new perspectives, in hearing what the next generation has to say, and in exploring approaches that challenge conventional ways of thinking about space and culture. At the same time, the field is facing unprecedented upheaval—from technological transformations to rapid social and political shifts, climate crisis, and economic instability. The architecture field has grown weary of repetition—the same established formulas, the same aesthetic norms. In this moment of uncertainty, many small studios like ours have emerged, offering fresh ideas and alternative ways of practicing architecture. We’re grateful to be part of this shift.