At Fublis, our Design Dialogues series is dedicated to exploring the minds of architects and designers who are redefining the built environment. Through in-depth conversations, we highlight the creative journeys, design philosophies, and industry contributions of leading professionals. These dialogues not only celebrate innovation but also provide valuable insights for both established practitioners and emerging talents.

In this edition, we feature Alva Roy Architects, a firm that seamlessly integrates research with design to create meaningful architectural solutions. Led by Alva Roy, the practice is known for its meticulous attention to materiality, spatial relationships, and human experience. Their projects push the boundaries of conventional design, prioritizing sustainability, contextual sensitivity, and the emotional resonance of space.

From reimagining multi-unit housing in Toronto to challenging traditional notions of indoor-outdoor living, Alva Roy Architects demonstrates how architecture can elevate everyday experiences. In this conversation, we delve into their approach to integrating research into the design process, balancing urban density with comfort, and crafting buildings that not only respond to their surroundings but also shape the way people live and connect.

Join us as we explore the vision and methodology of Alva Roy Architects—where every project is a dialogue between past and future, form and function, nature and structure.

Alva Roy Architects engages in both design and research simultaneously. How does ongoing research influence your design process, and can you share an example where research significantly changed the course of a project?

Alva Roy: At Alva Roy Architects, research is not something that follows design — it’s embedded in the process from the very beginning. Every project starts with a question: how can architecture not only serve its functional requirements, but elevate the human experience through context, material, and innovation?

Ongoing research allows us to engage deeply with site conditions, environmental performance, cultural patterns, and user behavior, often revealing insights that completely shift the trajectory of a project.

One example that stands out is the Tower of Love in Mississauga. Initially conceived as a minimalist high-rise, the project evolved significantly after research into urban loneliness, vertical community dynamics, and local zoning constraints. That research led us to integrate shared spaces and transitional zones within the vertical form — encouraging interaction, creating micro-neighborhoods, and ultimately rethinking what a tower could be for the people who live in it.

In that way, research isn’t just an analytical tool — it’s a creative catalyst that allows us to challenge assumptions and design with more purpose, depth, and relevance.

The Brother’s Residence is a triplex that carefully integrates into its urban surroundings while ensuring each unit maintains a sense of privacy and comfort. How did you approach the challenge of creating a multi-unit dwelling that feels both spacious and intimate for its residents?

Alva Roy: Designing a triplex that feels both spacious and intimate required us to approach the Brother’s Residence not just as a building with multiple units, but as a set of individual homes layered within a shared structure.

Located on a long and narrow lot in Toronto’s Bloor West neighborhood, the project had to navigate a tight urban footprint while respecting the scale and rhythm of the surrounding streetscape. Our goal was to ensure that each of the three families had a strong sense of identity, privacy, and access to light and outdoor space — all within a cohesive architectural language.

We began by carefully planning the layout across four levels to optimize both horizontal and vertical space. Each unit was given its own separate entrance and egress, along with independent mechanical systems, allowing the families to live autonomously without overlap in daily function.

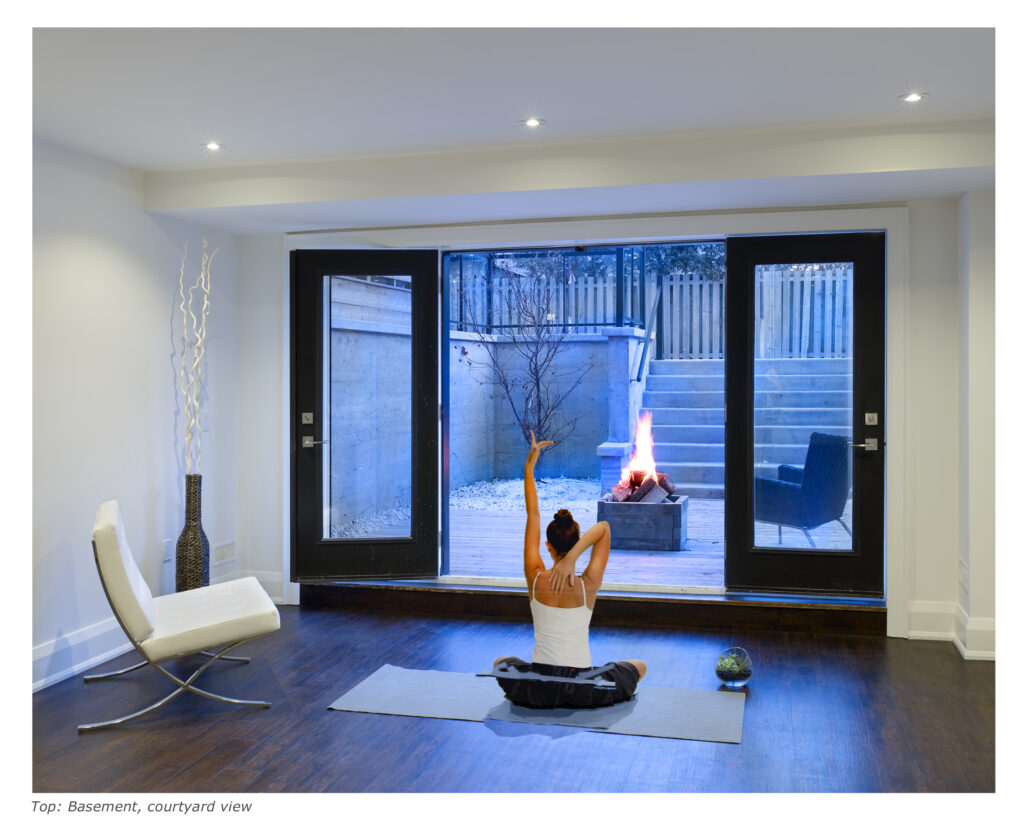

Spatial intimacy was achieved through a layering of private and shared zones, and through the thoughtful integration of outdoor elements. For example, the lower-level master bedrooms open onto a sunken courtyard, providing a sense of retreat while still engaging the site’s natural light. The top-floor unit includes a private front-facing terrace, and a rear balcony off the main floor ensures that every unit has a personal connection to the outdoors — something often missing in multi-unit dwellings.

Material choices also played a role in creating warmth and individuality. The use of Shou Sugi Ban cedar, Eramosa stone, and laser-cut aluminum screens introduced tactility and rhythm to the façade, while oak finishes and skylit stairwells brought softness and light into the interiors.

Ultimately, the Brother’s Residence is a study in how density can coexist with comfort — a way to create housing that is urban, efficient, and deeply personal.

©The Brother’s Residence by Alva Roy Architects

©The Brother’s Residence by Alva Roy Architects

The project is described as forming a distinct street edge with sharp, orthogonal geometries. How do you see the role of multi-unit residential buildings like this in shaping the character of Toronto’s midtown neighborhoods?

Alva Roy: Multi-unit residential buildings like the Brother’s Residence play a crucial role in shaping the evolving fabric of Toronto’s midtown neighborhoods. As the city grows and intensifies, there’s a need to increase density without sacrificing character, scale, or the human experience — and architecture is central to finding that balance.

With the Brother’s Residence, we were very intentional about using sharp, orthogonal geometries and material articulation to create a distinct street edge — one that feels contemporary yet sits comfortably within the existing context. The project engages with the rhythm of the street without replicating it, offering a fresh but respectful contribution to the neighborhood.

Midtown Toronto is defined by its eclectic mix of residential forms — from older single-family homes to walk-ups and commercial infill. Buildings like this one can act as transitional architecture, bridging the gap between past and future. They provide a model for gentle intensification: delivering more housing while maintaining a pedestrian-friendly scale and reinforcing the street’s identity.

Ultimately, I believe multi-unit projects should not disappear into the background — nor should they dominate. They should enhance the neighborhood with thoughtful design, contribute to urban vitality, and support a more inclusive, sustainable city.

©The Brother’s Residence by Alva Roy Architects

©The Brother’s Residence by Alva Roy Architects

Given your extensive experience with complex urban towns and institutional projects, how do you approach the challenge of integrating large-scale developments into existing cityscapes while maintaining a sense of place and identity?

Alva Roy: Integrating large-scale developments into existing cityscapes requires a balance between vision and respect — the ability to push design forward while honoring the unique DNA of a place.

Whether it’s an urban townhouse development or an institutional building, I always begin by asking: What’s already here? What are the patterns, materials, rhythms, and histories that define this neighborhood? From there, we work to introduce a project that doesn’t impose itself, but rather contributes to the ongoing conversation of the city.

My approach is rooted in research, observation, and empathy. I believe architecture at any scale must remain human-centered. Even the largest projects should create opportunities for intimacy, connection, and moments of quiet identity within the urban fabric.

For example, in past developments, we’ve used layered massing, public interface zones, and carefully scaled transitions to help large buildings feel grounded and welcoming. Materiality plays a key role as well — blending familiar textures and tones to create continuity while introducing a clear and contemporary design language.

In the end, it’s about creating buildings that belong — not just because they fit the zoning envelope, but because they resonate with the people who live, walk, and move around them every day.

©The Brother’s Residence by Alva Roy Architects

©The Brother’s Residence by Alva Roy Architects

Blanche Chapel House maintains a strong connection to the existing fabric of the neighborhood while introducing modern design elements. How did you ensure that the new massing and materials blended harmoniously with the original structure and surrounding context?

Alva Roy: With the Blanche Chapel House, our goal was never to mimic the original 1950s structure, but rather to engage in a respectful dialogue with it. The house sits within a traditional Toronto neighborhood near Bloor and Jane, where context and continuity are essential — but so is the evolution of how people live.

To maintain harmony with the existing fabric, we chose to work with traditional forms and familiar materials, but reinterpret them through a contemporary architectural lens. The upper mass, for example, is subtly offset from the original footprint, visually expressing the addition while creating spatial opportunities at the second floor. This gesture clearly defines the relationship between the old and new volumes — they are connected, but distinct.

The chapel-like form of the new entry acts as both a nod to the home’s history and a personal expression of the client’s identity. Its clean lines and carefully proportioned façade introduce modernity without disruption, while new material choices — including a restrained palette of wood and masonry — reflect both warmth and restraint.

In essence, the project was about finding balance: honoring the scale, texture, and rhythm of the neighborhood while introducing a new layer that feels both rooted and forward-looking.

©Blanche Chapel House by Alva Roy Architects

©Blanche Chapel House by Alva Roy Architects

©Blanche Chapel House by Alva Roy Architects

The project incorporates a chapel-inspired form that defines the façade and entry. What was the inspiration behind this element, and how does it shape the experience of the home from both the interior and exterior?

Alva Roy: The chapel-inspired form emerged as both a personal reflection of the client’s story and a symbolic gesture of transformation. The original 1950s house had a modest, unassuming presence, and the renovation was as much about honoring the past as it was about creating a new beginning.

We wanted to create an architectural element that gave the home a sense of dignity and serenity, and the idea of a chapel-like volume — with its clean lines, quiet strength, and sense of purpose — felt deeply appropriate. It not only shapes the identity of the façade but acts as a spatial anchor for the home.

From the exterior, it gives the house a defined presence within the neighborhood — contemporary yet timeless, expressive without being loud. From the interior, it brings in natural light through carefully placed openings, creating a moment of verticality and openness as you enter the home.

More than just a formal design move, the chapel element serves as a threshold — a transition between public and private, between the historical and the new. It invites a sense of calm, and sets the tone for the spaces that follow.

©Blanche Chapel House by Alva Roy Architects

©Blanche Chapel House by Alva Roy Architects

©Blanche Chapel House by Alva Roy Architects

Your firm emphasizes the use of honest materials in your projects. How do you define “honest materials” in contemporary architecture, and how do you balance material authenticity with modern innovation and client expectations?

Alva Roy: At Alva Roy Architects, we define honest materials as those that are true to their nature, origin, and expression — materials that age with dignity, reveal their imperfections, and tell a story through their texture, weight, and presence.

In our work, this often means using real stone, Shou Sugi Ban (burnt wood), raw sand-textured finishes, oak, and metal that is left exposed rather than coated or disguised. These materials carry cultural and sensory memory — they feel grounding, timeless, and human. They don’t pretend to be something else; they are what they are, and in that honesty, they create spaces that feel deeply rooted and emotionally resonant.

Balancing this material authenticity with modern innovation and client expectations requires careful consideration. We’re not nostalgic or dogmatic — we’re not trying to recreate the past. Instead, we look for ways to combine real materials with advanced detailing, thermal performance, and fabrication techniques so that the architecture feels both raw and refined.

Clients today often appreciate the tactile and visual richness that comes with real materials — but we also guide them through durability, maintenance, and cost-performance considerations, helping them understand why authenticity often brings long-term value, not just aesthetic impact.

Ultimately, it’s about building with integrity — materials that speak for themselves, and spaces that feel honest, grounded, and alive.

©Blanche Chapel House by Alva Roy Architects

©Blanche Chapel House by Alva Roy Architects

The Garden Void House challenges conventional notions of a garden by placing it at the core of the home rather than surrounding it. What inspired this approach, and how does it transform the way the residents interact with nature within their daily lives?

Alva Roy: The idea for the Garden Void House began with a simple question: What if the garden wasn’t around the house — but within it? Instead of treating nature as something external and decorative, we wanted it to be central, emotional, and alive — something the family could grow with, experience from every level, and feel connected to at all times.

The vertical garden begins at the basement level and rises through a void at the heart of the house, acting as both a spatial and emotional anchor. It brings light, greenery, and a sense of calm into the core of the home — reshaping how the residents experience nature on a daily basis.

This inversion of the typical layout challenges traditional ideas of how we relate to landscape. Rather than being separated from nature by walls or glass, the family is immersed in it — they live around it, move alongside it, and watch it change with the seasons.

The void also allows light to cascade into all levels of the home, creating a sense of openness and vertical flow that enhances both privacy and connection. Paired with the use of honest materials and strategically placed windows, the result is a home that is both grounded and uplifting — a space designed not only to function, but to nurture emotion, reflection, and growth.

©Garden Void House by Alva Roy Architects

©Garden Void House by Alva Roy Architects

©Garden Void House by Alva Roy Architects

You mention that Garden Void House avoids the typical “stick-on solar panel” approach and instead integrates sustainability into the architectural fabric. Could you share some of the most innovative passive design strategies used in this project to improve energy efficiency and comfort?

Alva Roy: At Alva Roy Architects, we believe that true sustainability begins with form, orientation, materiality, and how a space is lived in — not just by adding green technologies after the fact. In the Garden Void House, our goal was to integrate passive design strategies so deeply into the architecture that they feel invisible but essential to the experience of the home.

One of the most impactful strategies was the creation of the central vertical garden void, which acts as a natural light well and ventilation core. This void draws light deep into the basement level, reducing reliance on artificial lighting, and facilitates natural stack ventilation — allowing warm air to rise and exit while drawing in cooler air below.

The contrast of large and narrow windows was also intentional: larger openings were strategically placed on the north and interior-facing void side to maximize daylight without overheating, while smaller apertures on the sun-exposed elevations reduce heat gain and increase privacy.

Material selection played a key role too. We used thermal massing and natural, breathable materials to regulate internal temperatures and minimize mechanical loads. The building envelope was detailed to be highly efficient, reducing energy leakage and improving overall comfort.

©Garden Void House by Alva Roy Architects

©Garden Void House by Alva Roy Architects

©Garden Void House by Alva Roy Architects

Your projects consistently push the boundaries of architecture, blending innovation with deep respect for materials, nature, and human experience. Looking ahead, how do you see the role of architecture evolving in shaping not just buildings, but the way people live, connect, and experience the world?

Alva Roy: I believe the role of architecture is evolving from simply designing buildings to shaping the way we live, connect, and feel. In a time of rapid urbanization, social change, and environmental urgency, architecture has to be more than functional — it has to be meaningful.

Looking ahead, I see architecture as a medium through which we can reclaim slowness, authenticity, and emotional resonance in our environments. It’s no longer just about maximizing square footage or optimizing flow — it’s about creating spaces that support wellbeing, foster community, and reconnect people to nature and to themselves.

Materials will continue to play a vital role. We need to build with honesty and longevity, using materials that ground us and age with grace, while embracing innovation that serves both performance and poetic expression.

Technology will continue to evolve, but I believe the most important shift will be toward designing with intention — crafting architecture that is anchored in place, enriched by culture, and open to the lives that unfold within it.

At Alva Roy Architects, we’re interested in that future — one where architecture doesn’t just shape the skyline, but helps shape a more human, connected, and emotionally intelligent world.