At Fublis, our Design Dialogues series highlights the innovative minds shaping the future of architecture and design. In this edition, we speak with alsar-atelier, a practice that emerged during the pandemic and continues to challenge conventional approaches to architecture in the public realm.

Founded on the principles of adaptability, resourcefulness, and socio-economic responsiveness, alsar-atelier embraces a design philosophy that prioritizes necessity over convention. From reimagining urban spaces with repurposed materials to integrating ephemeral and mobile structures into informal environments, the studio’s work addresses pressing social issues through pragmatic yet inventive solutions.

In this conversation, we explore the influence of the studio’s pandemic-era origins, its approach to designing for socio-economically constrained contexts, and its commitment to sustainable, community-driven architecture. With recent projects such as the Hydroponics Module and Community Built Fog Catcher, alsar-atelier demonstrates how lightweight, prefabricated structures can serve as both functional solutions and educational tools for urban and rural communities alike.

As the studio gains international recognition, including a nomination for the Mies Crown Hall Americas Prize EMERGE, we discuss its evolving vision and how its unconventional methods might inform future large-scale projects. Join us as we delve into the thought process behind alsar-atelier’s work, uncovering valuable insights into the role of architecture in shaping resilient, equitable, and adaptable built environments.

How does alsar-atelier’s pandemic-born origin influence its approach to designing need-based architectures in the public realm?

Alejandro Saldarriaga Rubio: I still like to define my practice as a pandemic-born architecture studio because it has had such a strong influence on how I approach design. During the pandemic, I was asked to develop public proposals in an environment marked by socio-economic scarcity. This period pushed me to find design solutions outside the box, focusing on non-traditional materials and strategies to solve specific problems in the public realm. For instance, when government institutions or clients needed spaces, like restaurants reopening for outdoor service during the pandemic—such as in New York—there was no budget for new architecture. Public organizations also weren’t dedicating funds for design. As a result, we had to get creative, using recycled materials or repurposing infrastructure like scaffolding and concrete formwork to create functional spaces.

Moreover, these projects were inherently tied to ephemerality. The pandemic itself was an uncertain reality, and even though we were proposing architecture, we knew it wasn’t necessarily going to be permanent. The experience made me more conscious of how architecture could be disassembled rather than demolished—an idea that has shifted many of my design paradigms. I now think much more about the end of a project’s life cycle and how we can make temporary spaces that can easily be taken apart or repurposed.

Most of these proposals were aimed at addressing socio-economic inequities. For me, the pandemic was an emergency, but it lasted long enough to highlight chronic problems. Coming from Colombia in the Global South, I’m familiar with the informal growth of cities on the urban periphery, where people build without official permissions due to violence or socio-economic scarcity. These environments exist in a state of ongoing crisis, which is why the logic of pandemic architecture works so well there.

I’ve since built my practice around this “pandemic logic”—thinking outside the box with materials, considering the ephemerality of projects, and always keeping socio-economic needs at the forefront. This approach has led me to engage with issues beyond informal settlements, expanding into cities like the US, where socio-economic inequities are also prevalent. Moving forward, I’m interested in taking this methodology and applying it to larger, more permanent projects, such as social housing in Bogotá. My goal is to transform this logic into scalable solutions that have a lasting impact on communities in need.

Given the project low-tech Hydroponics Module’s emphasis on adaptability and reuse, how do you see this design evolving if replicated in other urban or rural settings with different environmental and social constraints?

Alejandro Saldarriaga Rubio: To answer this question, I would emphasize that this design is meant to be mobile and adaptable to different contexts. For example, Bogotá is located 2,600 meters above sea level, with a tropical climate that doesn’t experience distinct seasons. While it’s not necessarily cold, it can be quite chilly, particularly in the mornings. In this environment, having a greenhouse is crucial, since plants that grown in traditional agricultural settings could freeze at night. To address this, we wanted to create a greenhouse effect that could retain heat and ensure that the plants could thrive.

If this module were to be replicated in another tropical setting with a different altitude, like other areas of Colombia, the materials used might need slight adjustments. The design would have to generate a different environmental effect or temperature regulation to work effectively. Additionally, the water’s pH balance in hydroponics must be maintained, so temperature control would be essential for success.

On the other hand, if this design were placed in, for example, the Northeast of the United States, it wouldn’t work as intended. This is due to its lightweight and simple structure, which doesn’t provide the necessary thermal comfort or environmental control needed in colder climates. I believe this type of project would be more suited for the Global South, where we can reinterpret the materials and facade elements to suit the local climate.

©A low-tech Hydroponics Module by Alsar-Atelier

©A low-tech Hydroponics Module by Alsar-Atelier

©A low-tech Hydroponics Module by Alsar-Atelier

What were the biggest architectural challenges in designing a semi-permanent hydroponic module for an informal urban environment, and how did your team address them?

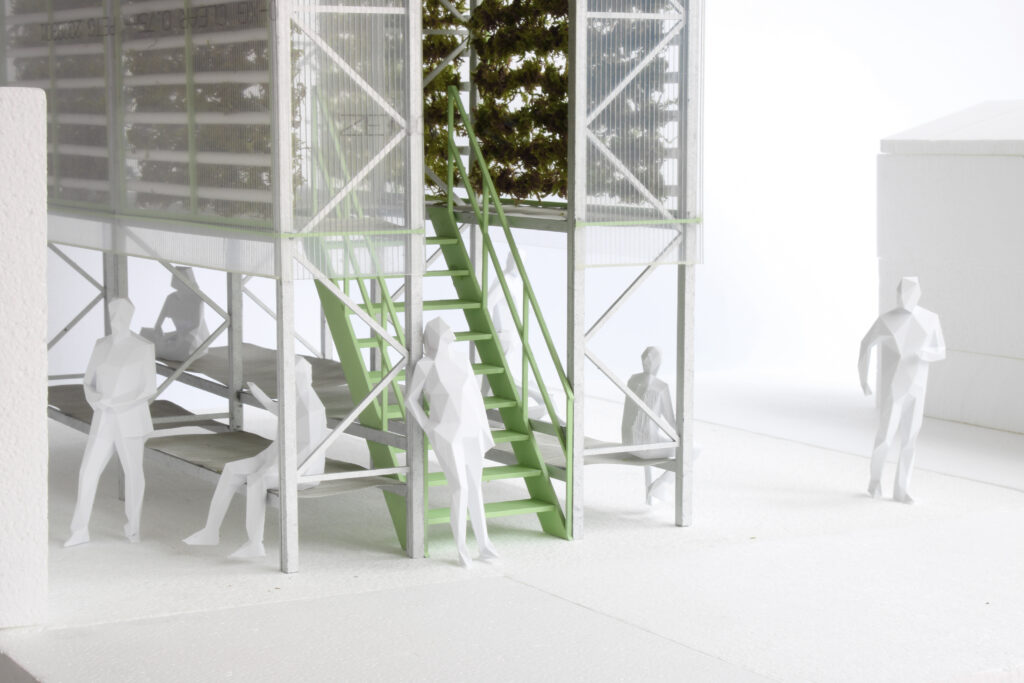

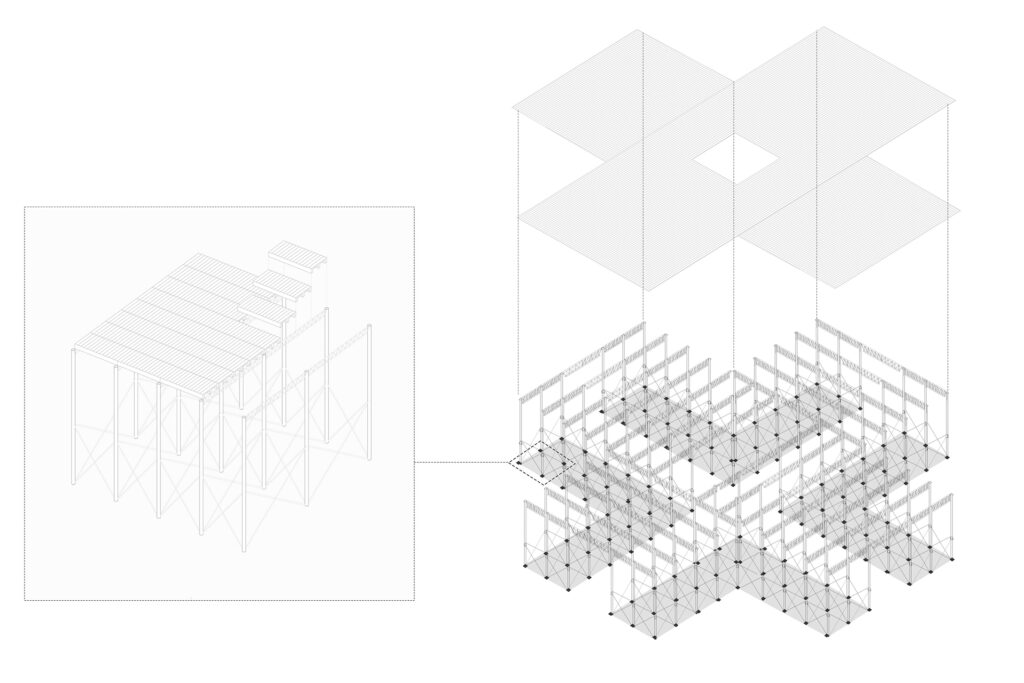

Alejandro Saldarriaga Rubio: The main challenge we faced was finding a material that could fit within the limited budget we had, which was $10,000 provided by NEACOL, a nonprofit organization based in Boston. While this is a significant amount in Colombia, it’s not an unlimited budget, so we had to be creative in sourcing materials that were cost-effective. Additionally, we had to consider the ephemerality of the project. We were working with Fondacio, a French nonprofit, which was renting a plot of land in an informal urban environment. Since they didn’t own the land, we needed to design a structure that could be disassembled and moved if needed.

The challenge was finding a material that was both affordable and modular, while also being easily transportable. Our solution was to repurpose an existing material—industrial shelving typically used in department stores like Home Depot. This shelving is inexpensive, structurally sound, and readily available through platforms like Amazon or eBay, making it a quick solution to meet our budget and mobility requirements.

By using this shelving system, we were able to address both the budget constraints and the need for a modular, temporary structure. The project is currently on the land rented by Fondacio, but it could easily be relocated if necessary.

©A low-tech Hydroponics Module by Alsar-Atelier

©A low-tech Hydroponics Module by Alsar-Atelier

With the project functioning as both an agricultural space and an analog school, how did you integrate educational considerations into the design to make learning an intuitive and engaging experience?

Alejandro Saldarriaga Rubio: In this project, we focused on how we distributed the interior spaces. If you look at the elevation of the proposal, the first floor serves as a flexible educational space, with tables and benches, while the actual hydroponic gardens are located on the second floor. The pedagogical experiences are mostly managed by the organization itself, as they run workshops with local community members, especially children from the nearby school.

The involvement of the community is crucial because they essentially become the administrators of the space. They ensure that the hydroponic gardens and the community gardens are functioning properly. Additionally, they help manage the community learning workshops that take place on the first floor.

Within this environment, particularly in the hydroponic module, community members are taught how to practice urban agriculture in informal settings, as well as how to develop healthy eating habits. They learn how to apply hydroponics in their own homes, grow their own vegetables in the hydroponic garden, and even cook and potentially process the produce to make it more commercially viable.

©A low-tech Hydroponics Module by Alsar-Atelier

How did the extreme time constraint of just four days shape your design decisions, and what were the key architectural strategies that allowed for such rapid assembly and disassembly in Alhambra’s Cross?

Alejandro Saldarriaga Rubio: The extreme time constraint of just four days played a crucial role in shaping our design decisions for the chapel. We were working under a very unique set of circumstances—the chapel was to be built in a parking lot for an elderly community in Bogotá, during the pandemic, and only for the span of Holy Week. The elderly community, already living in semi-isolation, faced even more challenges during the pandemic, especially when it came to socializing or going to church. Religion plays an important role in Colombian culture, and for these senior citizens, attending church is not just a matter of routine but also a vital part of their mental health and social engagement.

Given that we had to create a temporary space for this community, we focused on materials that could accommodate the extreme temporality of the project. Our challenge was to design something that could be assembled and disassembled within a very short period, so we knew we had to prioritize speed, efficiency, and functionality.

We considered scaffolding as an option, but it was a vertical material and, given the age of the users, we didn’t want them circulating in a vertical manner. We needed something that could be deployed horizontally and still offer the necessary structure. That’s when we thought of using concrete formwork, specifically the kind used in horizontal slabs for skyscraper construction. This material works for temporary structures in construction, as it holds concrete in place for just 24 hours before it’s removed—ideal for a project that had to be put up quickly and then taken down just as swiftly.

Not only did this material fit the time constraint, but it also offered a natural tectonic quality, with vertical elements arranged in a rhythm that, to me, resonates with religious architecture. The concrete formwork also gave the structure a sense of permanence, even though it was inherently temporary. The project itself was completed in half a day, and we were able to use it throughout the Easter period, providing a meaningful space for the community.

Ultimately, our focus on speed, the use of adaptable materials, and the understanding of the spiritual and emotional needs of the community led us to a solution that worked both pragmatically and aesthetically.

©Alhambra’s cross by Alsar-Atelier

©Alhambra’s cross by Alsar-Atelier

©Alhambra’s cross by Alsar-Atelier

Given that the chapel was dismantled and its materials returned to their original use, how do you think ephemeral architecture can influence future sustainable urban interventions?

Alejandro Saldarriaga Rubio: I think that’s a really interesting question, and it’s something I’m constantly exploring in my practice. I’m focused on how architecture that is disassembled or has an organic, ever-changing, or ephemeral nature can be repurposed in more permanent urban interventions. I like to think of the architecture I’m working on as having qualities similar to tactical urbanism—specifically, the principles of tactical urbanism. This involves temporarily taking over a public space, like a street, and creating a low-cost intervention. You then observe how it functions until it eventually transforms into a more permanent feature, like a public plaza or park. Ideally, this is the direction I’d like to take: seeing architecture serve as a successful initial experiment that informs and inspires a more permanent urban intervention.

©Alhambra’s cross by Alsar-Atelier

©Alhambra’s cross by Alsar-Atelier

What role does community engagement play in your design process, and how do you incorporate feedback from local residents into your projects?

Alejandro Saldarriaga Rubio: Community engagement in my design process really depends on each specific proposal, the accessibility of the community, and, quite frankly, financial and time constraints. Ideally, what I strive for is to define a project at a conceptual level—whether it’s a temporary chapel or a hydroponics module—so that we have a clear program in place. This allows us to gather valuable feedback from community members about what they imagine, what they like, and what they dislike. Typically, this feedback is collected through workshops, where we first ask community members to share their ideas. We then take those ideas and create a design, which we share with them again for further input. However, this process isn’t always as straightforward as it may sound. Sometimes, it’s challenging to find a space where a lot of community members can physically gather at a time and place that aligns with the project’s budget and timeline.

How does the studio balance the dual locations of Boston and Bogotá in terms of design philosophy, cultural influences, and project execution?

Alejandro Saldarriaga Rubio: I’m originally from Bogotá, and I did my undergraduate degree at La Universidad de los Andes, or the University of the Andes. That experience really helped me develop strong technical knowledge about how to build. Later on, I decided to pursue a master’s degree at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in Boston, where I learned about more conceptual approaches to architecture, which tend to be more skeptikal.

I think the combination of deeply understanding the construction logic of the Colombian context, mixed with more innovative and cutting-edge design approaches from the Global North, has led me to develop a dual design philosophy. I focus on reapplying ideas commonly found in the developed world and adapting them to the context of the Global South, which often involves cultural influences and materials that are specific to the region.

When it comes to project execution, I get asked about this a lot. To be honest, this is part of why I consider my studio to be a “pandemic studio.” During the pandemic, design proposals were being made digitally, via Zoom, and that shift allowed me to operate in a more remote way. I’ve been able to maintain a small team in Bogotá, which helps me oversee day-to-day construction, while I’m based in Boston. I engage with clients virtually, which makes it a manageable setup despite the distance.

Self-built environments often rely on brick and concrete due to familiarity and perceived durability in Community Built Fog Catcher. What strategies did your team use to convince the community of the feasibility of lightweight, prefabricated structures? Were there any initial resistances or misconceptions that had to be addressed?

Alejandro Saldarriaga Rubio: I understand where the question is coming from, but I’d say we didn’t exactly have to convince the community about the feasibility of the lightweight prefabricated metal structure we used for the Community Built Fog Catcher. The goal was more about providing an example of what could be done. It wasn’t really a project where we had to persuade the community to build with these materials. Instead, it was about showing them how they could visualize using this material in their own structures.

At the same time, with the hydroponics module, and in our third project, we’re working on how to introduce lightweight, more sustainable materials into informal environments. Ultimately, these projects are meant to serve as inspiration for community members to reapply these ideas on their own. Changing a traditional context, where brick and concrete are so deeply ingrained, is difficult, but the hope is that these examples spark new possibilities.

©Community Built Fog Catcher by Alsar-Atelier

©Community Built Fog Catcher by Alsar-Atelier

©Community Built Fog Catcher by Alsar-Atelier

Reflecting on alsar-atelier’s recent nomination for the Mies Crown Hall Americas Prize EMERGE, how does the studio envision its evolution in the next five years?

Alejandro Saldarriaga Rubio: Reflecting on our recent nomination for the Mies Crown Hall Americas Prize EMERGE, I see it as a pivotal moment for Alsar-Atelier. As the office has been gaining a more consistent flow of projects, I envision us evolving toward a more traditional practice methodology. While we will continue to focus on small-scale research projects—something that has always been central to our work—we are planning to explore more traditional architectural design projects in the near future. These will likely include multi-family housing, single-family homes, and possibly public competitions.

At the same time, we want to maintain a strong connection with academia, which has always been an important part of our identity. I also see us pursuing publications that explore our design methodology, particularly how we’ve adapted the three rules of pandemic architecture to different global contexts. We’re also interested in speculating on how this moment in time has shifted paradigms for architects and designers in the contemporary world.