In this edition of Design Dialogues, Fublis is proud to feature AD+studio, a Vietnam-based architectural practice known for its thoughtful, context-responsive designs that embrace the complexity of place, culture, and human experience. Rather than adhering to a fixed stylistic language, AD+studio approaches each project as a unique dialogue between environment, users, and the design team—an ethos that fosters architecture deeply rooted in locality while remaining open to innovation.

From exploring the layered roofscapes of Thai Nguyen in Stacking Roof House to reinterpreting the spatial depth of Hoi An’s historic townhouses in Rotating House, the studio’s portfolio reflects a keen sensitivity to both cultural memory and contemporary living. Their projects balance tradition and modernity with quiet confidence, often revealing surprises through spatial rhythm, material reuse, and nuanced storytelling.

In this conversation, AD+studio shares insights into their creative process, their engagement with Vietnam’s rich regional diversity, and the values that shape their work—from sustainability and emotional resonance to architectural education and long-term relevance. Their reflections offer not only a window into the evolving landscape of Vietnamese architecture but also inspiration for practitioners and enthusiasts worldwide.

AD+studio’s work consciously avoids developing a singular architectural language, instead embracing the diversity of local culture and user habits. How do you balance this openness with maintaining a consistent design quality across your projects?

Nguyen Dang Anh Dung: At AD+studio, we believe that every architectural work is shaped by the interaction of three core factors: the context, the users, and the designer.

– Vietnam’s built environment offers an incredibly stimulating “laboratory” for design — marked by vast geographical and climatic diversity, rich regional cultures, and a rapidly urbanizing landscape with uneven development across cities, rural areas, and transitional zones. These conditions form a highly complex yet fertile ground for experimentation, demanding adaptability while also offering the opportunity to develop context-specific solutions that are both inventive and rooted in place.

– The users – the people – are always the most dynamic variable. Every individual is a unique presence, and for us, they are the most important source of inspiration in the design process. Whether designing for a person, a family, or an entire community, we begin by observing their habits, behaviors, and needs — and sometimes even their memories or dreams. These are living materials that help us craft spaces that are not only functional, but also soulful, spaces that reflect their identity and rhythm of life.

– The designer, paradoxically, tends to be the least flexible variable. As individuals, we all carry our own limits, biases, and comfort zones. For this reason, the AD+studio is committed to expanding our perspectives by reading more, learning more, experiencing more, and above all, observing and listening more. We see each project not just as a finished product, but as the result of a continual process of study, dialogue, and reflection on everyday life.

From these three factors, architecture emerges – as a tangible, inhabitable form that can be felt, used, and lived with each day. Our designs are not about showcasing personal style, but about seeking harmony — between people, space, and context. If we can achieve that, then the quality of the project is ensured, and each building has the potential to become a meaningful part of life.

The Stacking Roof House project beautifully captures the layered roofscape of Thai Nguyen while introducing contemporary elements. What were some of the most significant design decisions you made to ensure this balance between tradition and modernity?

Nguyen Dang Anh Dung: There were three key strategies we adopted in designing the Stacking Roof House.

First, we retained part of the existing structure – including the foundation, floor slab, columns, and several concrete decks – elements that quite literally “rose from the ground.” This act of reuse was not only an economical decision, but also a way for us to engage with and inherit the memory of the land — a surface that has silently witnessed the lived history of the home.

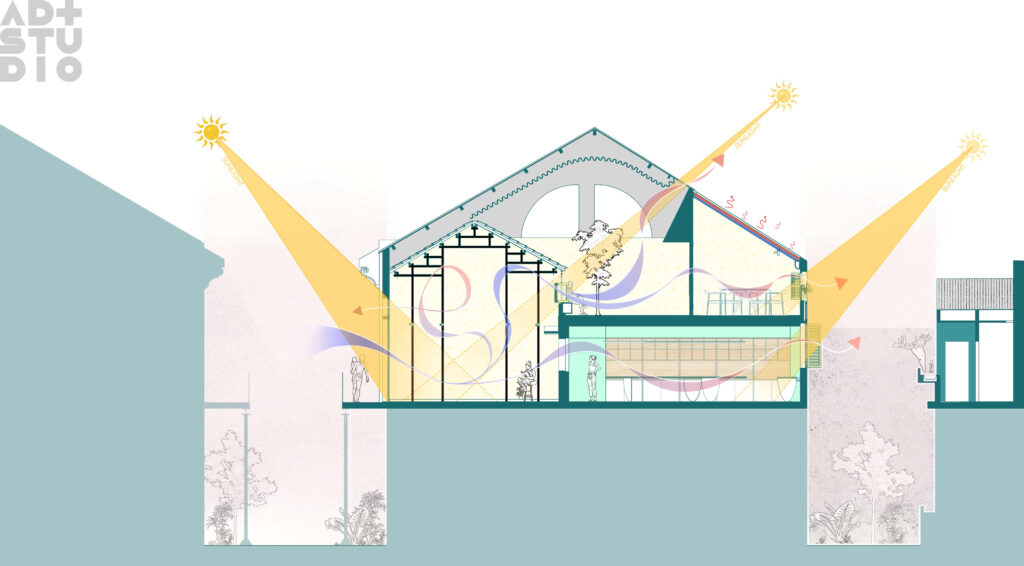

Second, we drew inspiration from the layered roofscape characteristic of Thai Nguyen’s urban fabric — a local vernacular element reinterpreted as a series of new roof structures placed atop the existing concrete frame. These roof layers employ a mix of materials — from translucent polycarbonate to metal over glass ceilings — depending on the function beneath, promoting natural ventilation while reducing heat gain from direct sunlight. In this way, the roof becomes more than just shelter; it becomes an aesthetic and climatic device — a means of reimagining the memory of the sky.

Third, we reorganized the “in-between” spaces based on the lifestyle of the client — introverted individuals with a deep affinity for nature. While the front block was kept deliberately enclosed to buffer the noise and chaos of the street, the rear of the house unfolds into an internal ecosystem. Private zones are nestled within a series of existing gardens, creating a sense of stillness and intimate connection — a place where one can slow down, embrace light and greenery, and find peace in everyday life.

©Stacking Roof House by AD+studio

©Stacking Roof House by AD+studio

©Stacking Roof House by AD+studio

The notion of “space compression” leading to a moment of surprise is a poetic gesture in the design. Could you speak more about how you conceptualize movement and discovery in residential architecture?

Nguyen Dang Anh Dung: We believe that, despite their differing mediums of expression, all forms of art ultimately strive toward a shared core value – beauty. By observing and learning from other artistic disciplines, we seek to discover expressive techniques that can be meaningfully applied to architectural design.

One of the influences that has shaped our spatial organization is the cinema of Ozu Yasujirō – the renowned Japanese director known for his use of static, low-angle shots that simulate the perspective of sitting on a tatami mat. This cinematic device not only evokes the intimacy of traditional domestic life but also reflects a deep appreciation for slowness and introspection. Drawing from this inspiration, we employ spatial compression, controlled openings, and a careful choreography of transitions to modulate rhythm within our architecture: a narrow corridor, an unexpected turn, a window framing a courtyard or a patch of sky – each shift is a quiet surprise, adding subtlety and richness to the experience of moving through the space.

©Stacking Roof House by AD+studio

©Stacking Roof House by AD+studio

In a context as culturally rich and varied as Vietnam, what are some specific lifestyle nuances or regional identities that have most surprised or inspired your architectural responses?

Nguyen Dang Anh Dung: Vietnam is a country rich in geographical and cultural diversity — each region bears its own unique set of traditions, lifestyles, landscapes, and climates. These contextual variations shape the way people live and interact, giving rise to distinct architectural characteristics across the country. In that sense, Vietnam is like a “living archive” — abundant, authentic, and full of inspiration — offering a fertile ground for architecture to truthfully reflect how people live, perceive, and connect with their surroundings.

Rather than being drawn to a specific location or identity, we seek out the unique essence inherent to each project. This diversity makes every work a journey of exploration: non-repetitive, non-prescriptive, and always beginning with openness. Yet, as the design process unfolds, each project tends to arrive at its own internal logic, often diverging from our initial expectations. It is this element of surprise that makes the creative process so compelling, like an open dialogue between the architect and the space.

At MODANO Coffee, inspiration came from the “nhà đá” “nhà đạp” (referring to the notion of a temporary and fragile dwelling – so impermanent that, if no longer needed, it could be knocked down with a simple push or kick – reflecting the seasonal, water-driven shifts in the Mekong Delta’s living environment) and the floating structures typical of daily life on water in the Mekong Delta. At CLOSER House, the challenge was to optimize a very limited footprint located deep within a dense urban fabric — leading to a strategy of spatial compression that still ensured ventilation, comfort, and a sense of human intimacy. At ROTATING House, we drew on the interwoven layering and inside-outside interplay of Hoi An’s traditional architecture to craft a flexible structure that balances privacy with openness. And at Stacking Roof House, the stacked roofing system evokes the silhouette of Thai Nguyen’s urban landscape — simultaneously symbolic and functionally responsive, helping to regulate the microclimate of the spaces below.

©Stacking Roof House by AD+studio

©Stacking Roof House by AD+studio

©Stacking Roof House by AD+studio

The rotation of both the ground and first floors is a powerful spatial gesture in the Rotating House project. Could you share more about how this decision emerged—was it initially conceptual or a response to constraints like climate, privacy, or feng shui?

Nguyen Dang Anh Dung: The ROTATING House project presented a series of complex design challenges from the initial analysis phase. First, the site is directly confronted by a rear-facing road axis. This condition raises concerns regarding feng shui, a culturally sensitive factor requiring careful consideration in the residential design. Second, the narrow gaps between neighboring buildings, ranging from only 2 to 4 meters, called for a precise strategy in placing openings on the side elevations to preserve privacy. Third, the views from the site were less than ideal: the front faces a similarly scaled building, while more valuable views – toward a museum and a public park – are only accessible at oblique angles to the left and right. Fourth, the house needed to ensure natural ventilation within a hot and humid climate, while also maintaining security in a densely populated neighborhood. Finally, the client expressed an interest in referencing the spatial model of traditional Hoi An townhouses, characterized by deep, tube-like proportions and layered spatial transitions. However, with a site depth of only 25 meters, the question arose: how could we recreate the spatial depth and rhythmic progression of a traditional Hoi An home, typically extending over 60 meters in length?

The solution came in the form of rotating the building 45 degrees – a move that ultimately addressed all of these concerns.

By reorienting the house off-axis from the main road, we not only mitigated the problematic feng shui condition but also reorganized the visual focus, redirecting views toward more desirable angles, such as the museum and park, while minimizing direct exposure to adjacent buildings to ensure privacy. The rotated massing created interstitial voids that allowed for controlled airflow and cross-ventilation even when the house is closed, effectively balancing ventilation and security needs. Additionally, the skewed wall planes introduced interior parallax effects, visually dissolving the building’s true end-point and evoking the sense of spatial depth and layered progression found in traditional Hoi An homes, despite the actual site being only 25 meters long.

evoking the sense of spatial depth and layered progression found in traditional Hoi An homes — despite the actual site being only 25 meters long.

©Rotating House by AD+studio

©Rotating House by AD+studio

©Rotating House by AD+studio

Hoi An’s traditional layered architecture and tile roofs are reinterpreted in a modern context here. What challenges or surprises did you encounter in translating this vernacular logic into a contemporary urban house?

Nguyen Dang Anh Dung: In developing the architectural language, we oriented the building’s exterior toward a modern aesthetic, with minimalist forms, a dominant white palette, and no decorative elements, ensuring it harmonizes with the overall spirit of the streetscape. However, once inside, the space begins to shift, gradually revealing a sense of familiarity through traditional elements: a warm yellow tone, characteristic tiled roofing, and an interwoven organization of interior and exterior spaces inspired by the architectural fabric of Hoi An’s ancient town.

The design technique of being ‘closed off’ on the outside and ‘open’ on the inside creates an engaging journey of discovery, where each viewpoint offers a different experience, sparking a dialogue between tradition and modernity, between past and present.

House XOAY was also the first project in which we experimented with organizing the entire spatial layout based on a diagonal orientation. Experiencing the structure at full scale, when only the raw walls had been erected, brought a surprise: we all felt disoriented when moving through the space, subtly guided by the directional geometry. Though this navigation effect was anticipated in the design, the unfamiliar sensation it created was beyond what we had imagined. This memorable outcome reinforced our intention to use parallax to blur the boundaries of spatial depth, unlocking multiple layers of perception.

©Rotating House by AD+studio

©Rotating House by AD+studio

You’re also an educator. How has your experience teaching architecture influenced your design process at AD+ Studio—or perhaps challenged it?

Nguyen Dang Anh Dung: An interesting difference between these two roles lies in the approach. At AD+ Studio, I take the initiative in directing design proposals for collaborators, making clear and deliberate decisions. Each project must meet a certain quality standard before it is released—this is a rigorous practice process to ensure professionalism and responsibility in the field. However, in teaching, I intentionally follow the students’ individual approaches. I don’t teach them a formula or a specific style, but rather help them interpret context, frame questions, and build a workflow, through which they can develop their own ideas. My role is to accompany, guide, and help them go further on their creative journey.

Although the approaches differ, I believe there’s a methodological similarity between architectural practice and teaching: both involve a continuous process of asking questions, searching for answers (sometimes with guidance), refining ideas, and arriving at solutions. It’s a cycle of iteration and growth.

Teaching also helps keep my design thinking fresh, thanks to frequent interaction and dialogue with students, a generation with a sharp, distinctive perspective. Through them, I gain insights into the shifting needs and lifestyles of young people, who are both the studio’s main clients and the driving force behind emerging social trends. They’ve grown up amid rapid economic development, embracing a lifestyle that values openness, responsibility, enjoyment, and individuality. This also brings new demands for architecture, not only in form, but in how space is created to truly reflect the spirit of the times.

©Rotating House by AD+studio

©Rotating House by AD+studio

©Rotating House by AD+studio

How did you navigate the balance between preserving the architectural memory of Hao Sy Phuong and introducing modern functionality—especially in a building that’s not officially protected in the The Core | AD+ Office project?

Nguyen Dang Anh Dung: The strong impression of the shared atrium space in the neighborhood when I first visited—just as a guest—deeply influenced and eventually inspired the design concept when I had the chance to use one of the apartments as my own design studio. The fact that the building was not listed as a heritage site also gave us the opportunity to intervene in its structure, layout, and spatial details.

The Core is located in the Hào Sỹ Phường neighborhood, where typical tube houses are divided into two parts: the front opens onto a shared courtyard, while the rear connects to a vertical core space. In the communal front area, we made minimal interventions, preserving original elements as a way of respecting the historical value and surrounding context. However, in the rear—now the new office—the design language was completely simplified. We used neutral colors, an open layout, and natural light to create an airy, calm space.

The central design idea was to respect and emphasize the shared core spaces—buffer zones that are both functional and emotionally evocative. Instead of using all the available area for physical functions, we intentionally condensed them, leaving behind ‘a void.’

This vid acts as a transitional space between the old and the new—where past and present can engage in dialogue. It allows the layering of time to be felt more clearly, adding depth to the spatial experience.

©The Core by AD+studio

©The Core by AD+studio

©The Core by AD+studio

Reusing original roof tiles and preserving certain spatial relationships show a deep respect for material memory. Could you talk about the emotional or symbolic value that these gestures carry for you and your team?

Nguyen Dang Anh Dung: To me, this is a way of saying: “We are building something new, but we’re not forgetting the old.” Architecture is one of the few things that allows people to see time with their eyes. A worn-out tile may not be beautiful, but it has been on a roof for 30 years, enduring the rain and sun, witnessing the comings and goings of people. That history imbues it with an emotional value that new materials lack. We don’t use old tiles just for cost-saving purposes; we use them because we want the residents — and even visitors— to feel that the story isn’t over, and that the people living there are the ones who will continue writing it.

More broadly, this behavior also reflects a sustainable mindset in architecture – one that views historical and cultural values as integral to the development of modern living spaces. Rather than creating a rupture between the old and the new, architecture functions as an accumulative system, where layers of value are intentionally arranged and inherited. In the ever-changing urban landscape, designing with a long-term, stability-oriented perspective – rather than chasing short-term trends – helps shape an architecture that is both deep-rooted and sustainably adaptive.

©The Core by AD+studio

©The Core by AD+studio

As a studio that draws so deeply from cultural memory and lived experience, what do you think architecture should feel like—beyond what it looks like—for the people who inhabit it?

Nguyen Dang Anh Dung: Architecture should not stop at merely fulfilling functional needs or expressing form; it must also evoke a deep sense of connection with both the past and present of those who inhabit the space. I believe that is the feeling of belonging—when we enter a space and know that we are here, we are alive, breathing, and fully present. A beautiful house can leave a strong impression, but a livable house is one that brings calm, safety, and the freedom to be oneself. This sense of belonging can stem from elements that may seem simple but are deeply meaningful—such as harmonious interaction with nature, smooth transitions between spaces, or design details that recall memories and cultural values of individuals or communities.

Architecture should not be loud or imposing; it should create an environment where people can live authentically, deeply, and closely connected to nature and their own emotions. When I design, I always hope the users can feel a gentle transition between layers of space—or, if possible, between the past and the present. A building is not just a shelter; it is a place that nurtures relationships, memories, and emotions. Architecture can serve as a bridge between generations, creating a space where every time someone enters, they feel welcomed and as if they are part of a larger story.