At Fublis, our Design Dialogues series is dedicated to showcasing the innovative minds and creative journeys of architects and designers who are shaping the future of our built environment. Through in-depth conversations, we explore their unique perspectives, celebrate their achievements, and share insights that inspire both peers and emerging talent.

In this edition, we speak with 35-51 ARCHITECTURE, a studio recognized for its poetic yet purposeful approach to design—where cultural heritage, material sensibility, and spatial experimentation converge. Known for projects like Dasht-e-Chehel Villa, Vanoosh Villa, and Shafaq Tomb, the studio reflects a deep commitment to context-driven architecture that bridges past and present.

From reinterpreting vernacular forms to designing immersive spaces that respond to climate, culture, and community, 35-51 ARCHITECTURE offers a compelling vision of what timeless, thoughtful architecture can be in a rapidly globalizing world.

Your studio is known for merging artistry with functionality while staying rooted in both global standards and local context—how would you personally define your design ethos, and how has it evolved as you’ve navigated different cultures, materials, and client needs?

Hamid Abbasloo: Our design ethos is rooted in cultural continuity through reinvention, proving that beauty and utility can coexist. We see architecture as a bridge between past and present—preserving local identity not by replication but by reinterpretation. Over time, as we’ve worked in different climates and with diverse materials, that core belief has remained constant; what has evolved is our palette of strategies, materials, and our responsiveness to client needs.

The design of Dasht-e-Chehel Villa blurs the boundary between indoors and outdoors, especially in a cold climate. How did you balance the psychological comfort of enclosure with the openness that invites nature in—even during snow or rain?

Hamid Abbasloo: We believe true comfort combines shelter with sensory connection. In a landscape of snow and wind, the challenge is to create refuge without isolation. The diagonal roof cut and north facing glazing invite snow and rain to become poetic elements rather than obstacles. Residents can sit under the extended roof during storms—physically sheltered yet sensorially connected to the weather. Psychologically, this threshold acts as a buffer: it feels “outside” yet remains safe. Meanwhile, the Trombe wall on the southern façade stores daytime heat to warm the interiors at night. By controlling exposure—through transparency, strategic openings, and transitional spaces (like ramped pathways)—we ensure the landscape is always an immersive presence. The result is a continuum rather than a binary of in and out: a space that nurtures both our instinct for refuge and our yearning for elemental exposure.

©Dasht-e-chehel villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Dasht-e-chehel villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Dasht-e-chehel villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

The diagonal cut and orientation toward the north view are striking decisions. Could you share more about how this spatial strategy influenced the daily experience of the residents—and perhaps even their behavior within the space?

Hamid Abbasloo: The diagonal cut served as both a spatial and psychological intervention. By angling the building’s axis toward the northern view, we transformed a static corridor into a dynamic, view focused spine that guides movement and daily rituals. Residents naturally gravitate toward this “heart” of the villa—whether preparing meals, reading, or gathering—because the space frames the landscape like a living painting. The cut also creates sheltered outdoor zones along the ramp, encouraging people to linger outside even in cold weather. Over time, we observed that this layout fosters a slower, more deliberate engagement with the environment; the architecture doesn’t just accommodate life but gently shapes it.

©Dasht-e-chehel villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Dasht-e-chehel villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Dasht-e-chehel villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

Can you walk us through how your design approach shifts when working in vastly different cultural or geographic settings? What remains constant, and what adapts?

Hamid Abbasloo: Our core principle—treating context as collaborator—remains unchanged, though its expression adapts to each setting. In northern Iran’s humid climate (Vanoosh Villa), we prioritized ventilation and green roofs; in the desert (Shafaq Tomb), we reinterpreted sabats (covered passageways) to combat heat. Culturally, the same applies: a villa’s privacy in Iran might manifest as dispersed pavilions, while elsewhere it could take the form of layered thresholds. What remains constant is our focus on sensory storytelling—using architectural elements to evoke a sense of belonging.

©Dasht-e-chehel villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Dasht-e-chehel villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

Vanoosh Villa challenges the idea of a centralized home by distributing key functions across the site. What inspired this spatial separation, and how has it impacted the way residents interact with both the architecture and the landscape?

Hamid Abbasloo: Vanoosh Villa’s dispersed plan was inspired by the archetypal Iranian home organized around a central courtyard. By separating the sleeping, cooking, and gathering zones into distinct pavilions, we created a village like microcosm where movement through gardens, shaded corridors, and past reflective pools becomes a ritual. This layout fosters both connection and solitude: family members can retreat to private pavilions yet remain linked through visual axes and shared outdoor spaces. The landscape itself becomes an active participant, and the retractable walls allow the villa to “breathe” with the seasons, blurring the boundary between architecture and landscape.

©Vanoosh Villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Vanoosh Villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Vanoosh Villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

There’s a poetic rhythm in the villa “opening to welcome and closing to defend.” How did Iranian vernacular traditions influence your interpretation of openness, privacy, and protection in this design?

Hamid Abbasloo: Iranian architecture has long employed layers—screen walls, circulation, courtyards, spatial organization —to balance hospitality with privacy. In Vanoosh Villa, we reinterpret this tradition as a living “veil” of climbing plants on the semi open roof, which filters light and sightlines. The phrase “opens to welcome, closes to defend” reflects this duality: corridors between pavilions can be enclosed for intimacy or opened to create fluid, guest friendly zones.

©Vanoosh Villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Vanoosh Villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Vanoosh Villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

In a globalized world where aesthetics can feel increasingly homogenized, how does your team preserve or rediscover a project’s unique local identity?

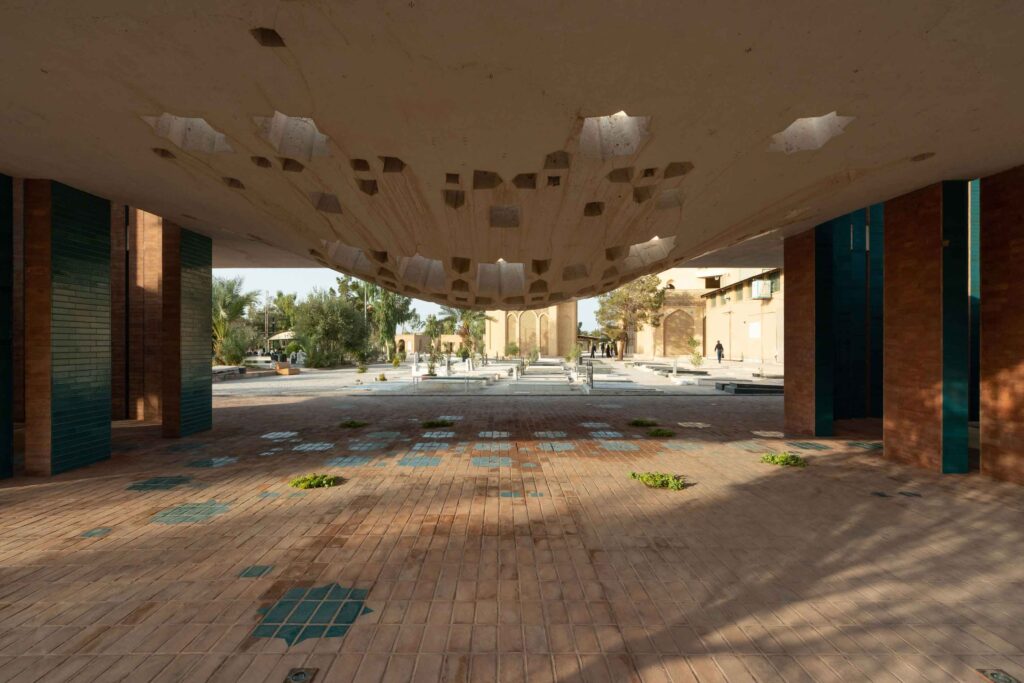

Hamid Abbasloo: Today’s homogenization affects not just forms but also concepts—sustainability, flexibility, inclusivity, connectivity …. We see these universal ideas as starting points, not endpoints: they’re a canvas we paint with pigments drawn from place specific conditions—local rituals, climate, and site and so on. For example, the cantilevered roof in Dasht e Chehel Villa employs a universal structural technique, yet its diagonal thrust is oriented to frame the site’s mountains, transforming a technical gesture into homage to the terrain. In Shafaq Tomb, that same principle is reinterpreted as a modern sabat, echoing traditional desert passageways in the region. Through such contextual adaptations, we preserve and rediscover each project’s authentic identity.

©Vanoosh Villa by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

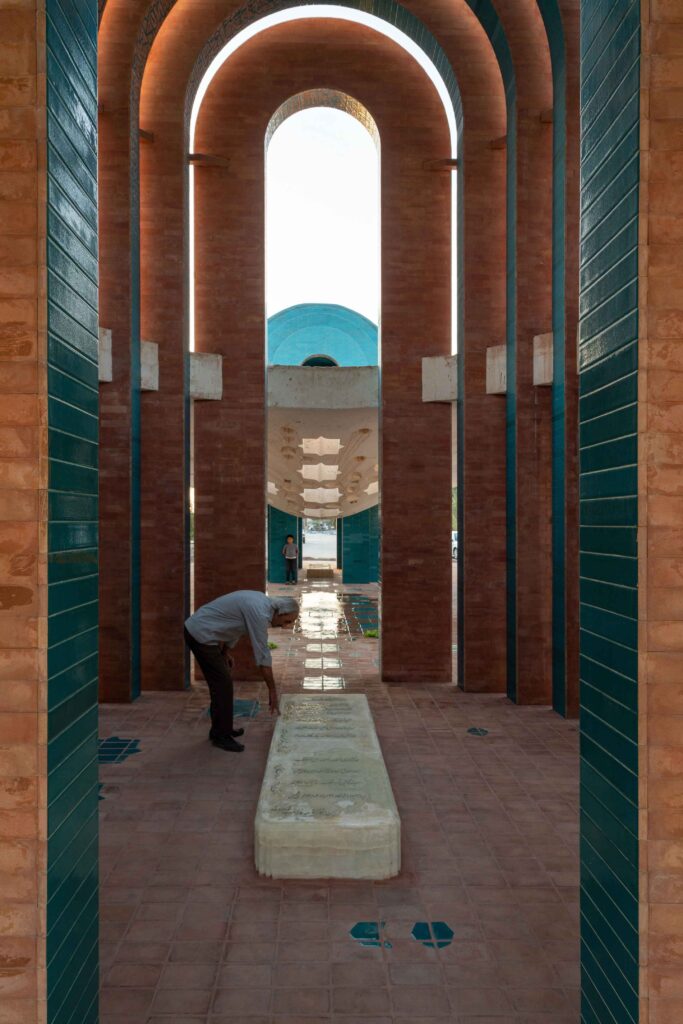

Shafaq Tomb reframes traditional elements like the dome and inscription in a more accessible, human-scale way. What guided your decision to reinterpret these powerful symbols, and how do you think it shifts the visitor’s experience of sacred space?

Hamid Abbasloo: “Democratizing” symbols of sanctity along with a personal yet universal impulse: the childlike desire to touch the untouchable. In Iranian architecture, domes have long symbolized celestial grandeur—elevated, distant, and reserved for contemplation from afar. But as children, many of us yearned to reach out and feel these majestic forms, to demystify their sacred aura through tactile connection.

Similarly, the calligraphic inscription, freed from its static place, now flows across the walls as a dynamic artwork—inviting touch and contemplation. This democratization shifts the visitor’s experience: the sacred is no longer a realm above, but a space among us. Pilgrims transition from awe to belonging, realizing that reverence can coexist with accessibility.

©Shafagh Tomb by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Shafagh Tomb by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Shafagh Tomb by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

You’ve drawn from “Sabats”—vernacular desert architecture—for climate responsiveness and gathering space. How important is it for you to embed passive strategies from local traditions into contemporary forms?

Hamid Abbasloo: Vernacular strategies are time-tested dialogues between people and place—discarding them would be like ignoring a language. So they aren’t nostalgic; they’re optimized wisdom. By embedding them into contemporary forms, we ensure buildings perform sustainably while nurturing cultural memory. After all, passive design isn’t just about energy—it’s about legacy.

©Shafagh Tomb by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Shafagh Tomb by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Shafagh Tomb by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

©Shafagh Tomb by 35-51 ARCHITECTURE office

In your practice, how do you define timelessness in architecture—and what values or design decisions do you believe help a building remain meaningful across generations?

Hamid Abbasloo: The idea of “timelessness” can indeed be misleading if we assume it means a building exists outside of time or context. Nothing material—whether a home, a garment, or a tomb—truly transcends its era. A house from 200 years ago, with its thick walls and enclosed courtyards, might feel foreign to us today, just as our glass-walled villas might baffle future generations. But what can transcend time is the emotional language embedded in architecture—the way spaces stir feelings that resonate across generations, like a love poem written centuries ago that still moves us today.